Termite mounds inspire climate-friendly air conditioning

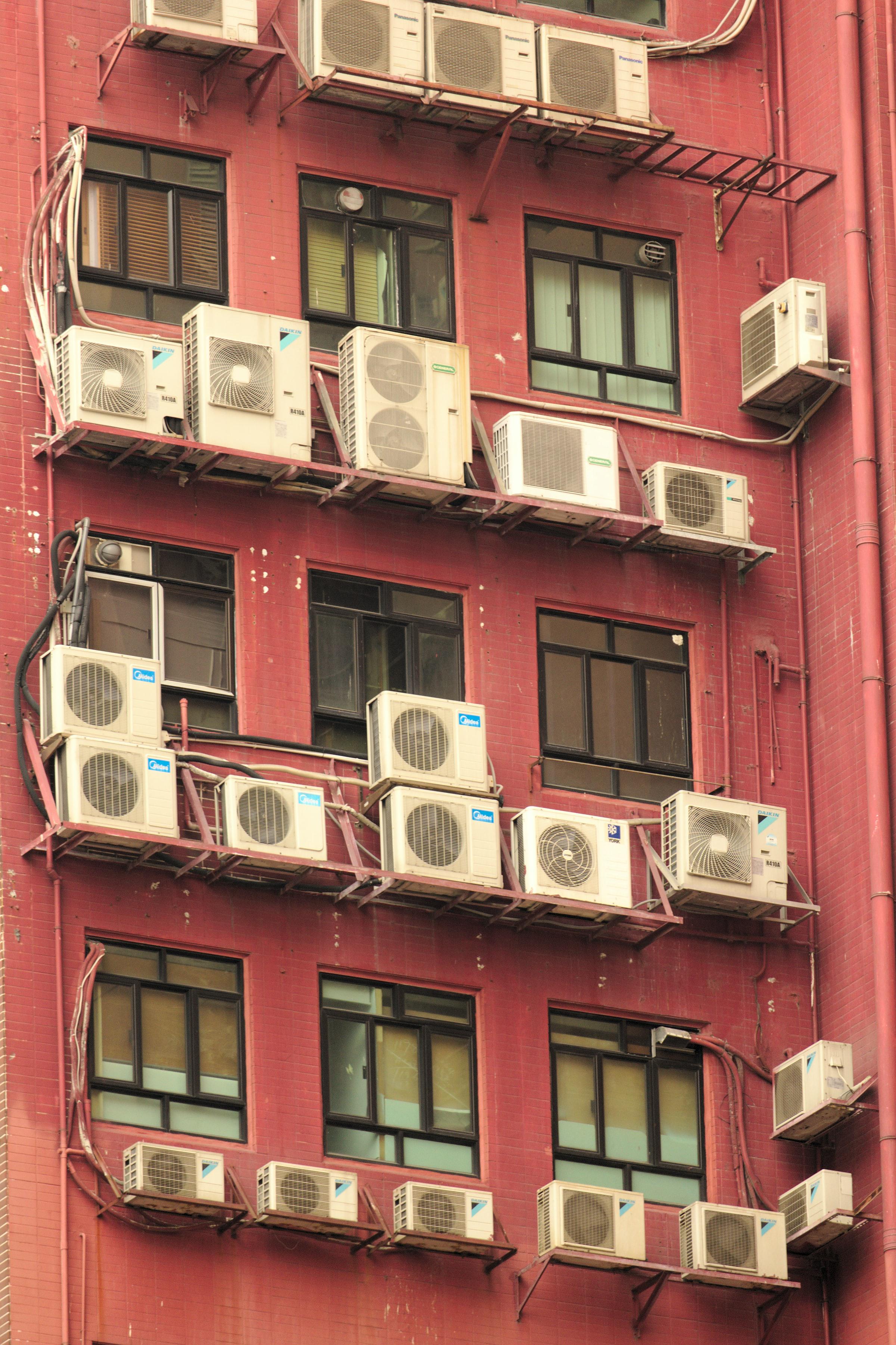

- Buildings in warm climates around the world rely heavily on air conditioning, but this consumes a vast amount of energy.

- The mounds that are key to the termite’s success — a staggeringly complex tangle of interconnected tunnels, channels, and chambers — are widely considered some of the greatest feats of engineering in the natural world.

- The tunnels act as an advanced ventilation system to drive air circulation throughout the entire colony.

Inspired by the networks of tunnels found in termite mounds, a pair of researchers has shown how smart building materials could be used to improve air circulation in indoor spaces, without drawing any power. Their discovery could lead to a far cheaper, and more sustainable, alternative to air conditioning.

The challenge: As our planet heats up, the need to keep our indoor spaces cool and comfortable is becoming more and more critical every year, as heat waves become longer and hotter. Today, buildings in warm climates around the world rely heavily on air conditioning, but this consumes a vast amount of energy.

According to the IEA, our air conditioning needs now take up some 20% of all the electricity consumed by buildings globally. Much of this power comes from burning coal or gas, generating an immense carbon footprint, which only exacerbates the problem further.

The inside of a termite mound is a staggeringly complex tangle of interconnected tunnels, channels, and chambers.

Inspiration from nature: One humble insect is doing a far better job at handling this challenge.

Since the time of the dinosaurs, mound-building termites have been living in energy-hungry cities with millions of inhabitants, often enduring searing temperatures in some of the harshest environments on Earth.

The mounds that are key to the termite’s success are widely considered some of the greatest feats of engineering in the natural world — and for some researchers, the ability to mimic their designs could be one of the most promising solutions to our growing dependence on air conditioning.

Natural ventilation: The inside of a termite mound is a staggeringly complex tangle of interconnected tunnels, channels, and chambers. Together, they act as an advanced ventilation system to drive air circulation throughout the entire colony.

Researchers still don’t fully understand how the layout of tunnel networks keep termite mounds cool.

In many ways, a mound and the millions of insects living inside function much like a single living organism: using wind energy to exchange the carbon dioxide the insects produce with the oxygen in their surroundings, while also maintaining safe and comfortable temperatures and humidities — even when conditions outside are far less hospitable.

Today, however, researchers still don’t fully understand how the layout of these tunnel networks achieve this feat.

Harvesting wind energy: In a new study published in Frontiers in Materials, David Andréen at Lund University in Sweden, together with Rupert Soar at Nottingham Trent University in the UK, hypothesized that these airflows are driven by gentle oscillations in the wind passing around the mounds.

As they interact with the air in the branching tunnels inside, the duo predicted these oscillations should drive turbulent flow patterns, which help air to flow more efficiently throughout the entire network.

In their experiment, Andréen and Soar aimed to find out how these flows can be generated by wind energy, and whether engineers could copy them. To test their prediction, the researchers represented the interior structures of termite mounds with a series of simple, 3D-printed “metamaterials.”

Smart materials inspired by nature could slash the cost and energy requirements of air conditioning.

Metamaterials are a fast-growing family of structures, in which small, artificial structures are arranged and combined to produce material properties which can’t be found naturally — just as termites build up their networks from soil, saliva, and dung.

The metamaterials used in this experiment were far less complex — featuring simple networks of narrow, interconnected channels, which connected two larger pools of water or air. But when the geometry of these channels was just right, gentle oscillations in one of the pools generated chaotic patterns that caused fluid to flow into the second pool more efficiently, just as Andréen and Soar predicted.

Nature-inspired buildings: If similar behavior could be reproduced in larger, more complex metamaterials, Andréen and Soar hope it could one day lead to a new class of building materials that could capture the wind energy surrounding them to control the flow of air passing through them — all without drawing any power.

If our buildings could harness this cooling power using smart materials inspired by nature, we could ultimately slash the cost and energy requirements of air conditioning.

This article was originally published by our sister site, Freethink.