Three strange takes on the philosophy of music

Music is a universal human experience. From banal elevator music to soul-shaking symphonies, music is anywhere and everywhere. It shouldn’t be a surprise, therefore, that philosophers had something to say about it — though some of their ideas were a little odd. Let’s consider three of them.

Plato thought some music must be banned

Plato was a student of Socrates. While many of his ideas serve as the foundations of Western philosophy, his takes on music were especially curious. Plato thought music was valuable because it imitates our emotions. He argued that it could be used to improve education and the moral fiber of society. But, like a grumpy grandpa, he also blamed changing musical tastes for the rejection of authority and subsequent unrest that followed the Persian War.

This might explain why in Republic he argues that what music can be performed should be strictly regulated by philosopher-kings. He concluded that most music modes should be banned. If Plato had his way, we would be left with just the Dorian and Phrygian modes, which are supposedly fitting for warriors and men working in peacetime, respectively. Other modes, like Lydian, allegedly made people lazy. As an analogy, this would be like blaming all of society’s ills on songs that were written in E major. To Plato’s credit, it is a novel argument.

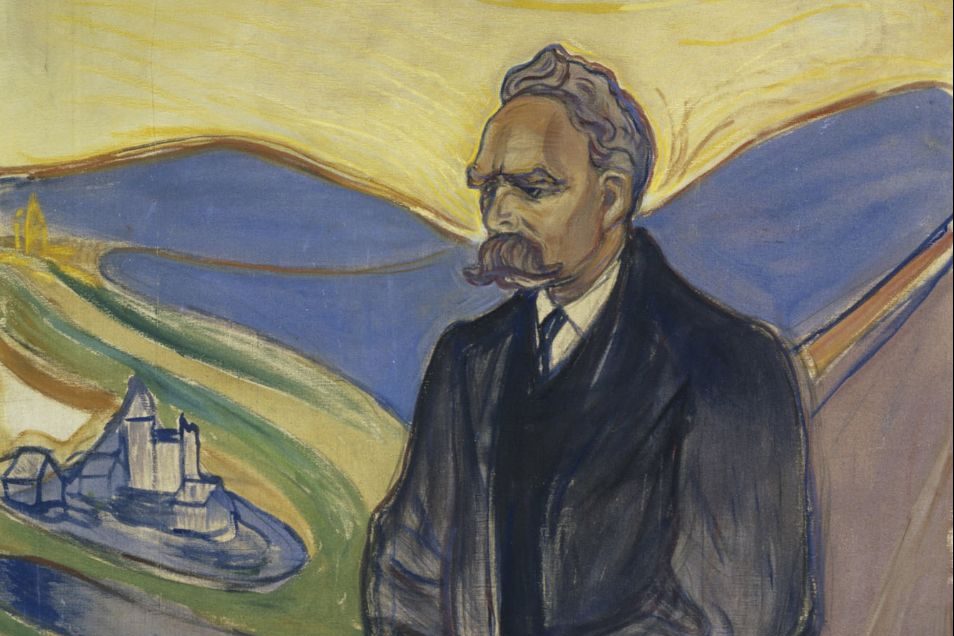

Schopenhauer thought music was reality made manifest

Arthur Schopenhauer was a German philosopher working in the 19th century. He is best known for his pessimistic worldview, his introduction of Buddhist and Hindu ideas into German philosophy, and his love of music.

To grasp his take on music, you have to understand how Schopenhauer viewed the world. He wrote that there is only one thing we can understand in itself, our bodies. Our bodies are driven by “Will” or “the Will to Live,” which we feel as striving and desiring. He argues that this allows us to realize that everything else is, at the metaphysical level, Will. The world we interact with is the representation of this Will. Since Will is impossible to satisfy, the world is marked by suffering. Only in moments when we negate the Will can we find some peace. Certain things, like artwork, allow us to have a similar experience.

Music enjoys the position as the greatest of all art forms. He says this is because it can represent the Will itself rather than just parts of it. This puts art on the same level of manifestation as the entire world. There is a reason he believed, “Music could exist even if there were no world at all.” It’s not that music is able to make us feel things that is important; instead, it’s that it allows us to experience will Without having to feel it. It gives us moments of liberation of desire and connection to the higher truth: Will.

On an unrelated note, Schopenhauer was a mean old man who believed the world we live in is terrible and that life is suffering. He once pushed a woman down a flight of steps because she was talking too loudly near his door and was relieved at her death years later as it ended the restitution payments he sent her. Music was one of the few things he sincerely enjoyed.

Adorno believed pop music led to fascism

Theodor W. Adorno was a Marxist philosopher working with the Frankfurt School. He was very concerned with how music mixed with sociology and politics. Unlike the others on this list, Adorno was a classically trained composer and well-versed in modern music theory. However, that didn’t save him from having a very unique take on popular music.

Adorno argued that, at its best, music can show the contradictions inherent in the society that produced it without being the main point of it. For example, he praised the composer Arnold Schoenberg and his atonal music because his system broke free of existing limitations, followed a new logic rather than trends, and required focus to enjoy. On the other hand, popular music was a mere product of the “culture industry.” He disliked popular music because it was a commodity with limited artistic merit and the potential to drive the masses toward homogeny and fascism — which meant that all jazz stinks all the time.

Adorno is infamous for associating all jazz with his notions of “popular music.” He dismissed both the genre and its defenders. For example, he argued that while jazz is seemingly liberating through encouraging improvisation and unheard-of levels of syncopation, it still often relies on common time and a strong kick drum. It appeared to be a bold new thing, while still being something that could be mass-produced and sold to customers. He argued that the multiracial aspects of jazz in the 1930s also had been incorporated into the marketing scheme.

His take has been attacked as racist, Eurocentric, and misinformed. Marxist historian and music critic Eric Hobsbawm called the writings “some of the stupidest pages ever written about jazz.” His student and jazz guitarist Volker Kriegel reported that Adorno had no idea who John Coltrane or Charlie Parker were while he continued to bash their genre. Apologists for Adorno suggested that he was attacking jazz as a commodity that existed in late 1930s Germany. At the time, it did have elements he would later critique more broadly.

In either case, he continued to despise the genre in his writings on cultural issues until he died in 1969. That was long after jazz had split from pop music. He also found time to dislike 1960s folk music and the Beatles.