“Mad King” behavior: A prediction for how 21st-century nuclear war would unfold

- Annie Jacobsen’s 2024 book Nuclear War: A Scenario outlines what total nuclear war would look like through a play-by-play approach.

- Jacobsen critiques the notion of nuclear deterrence, highlighting the risks of miscalculations and the increasing threat posed by global leaders like North Korea’s Kim Jong Un.

- Despite the grim outlook, Jacobsen finds hope in historical events, such as Ronald Reagan’s shift toward nuclear disarmament after recognizing the dangers of nuclear war.

“In the first fraction of a millisecond after [a] thermonuclear bomb strikes the Pentagon outside Washington, D.C., there is light. The light superheats the surrounding air to millions of degrees, creating a massive fire-ball that expands at millions of miles per hour. Within a few seconds, this fireball increases to a diameter of a little more than a mile (5,700 feet across), its light and heat so intense that concrete surfaces explode, metal objects melt or evaporate, stone shatters, humans instantaneously convert into combusting carbon. The five-story, five-sided structure of the Pentagon and everything inside its 6.5 million square feet of office space explodes into superheated dust from the initial flash of light and heat, all the walls shattering with the near-simultaneous arrival of the shock wave, all 27,000 employees perishing instantly.”

Nuclear War: A Scenario is the latest book by Pulitzer Prize-nominated journalist Annie Jacobsen. As its title suggests, it’s structured like a drama, walking readers through what a nuclear war might look like over 72 minutes, from launch to impact, and then over centuries to humanity’s extinction. Inspired by fellow author Alan Weisman’s 2007 “science-based non-fiction” bestseller The World Without Us, which imagines Earth’s ecosystem recovering after a hypothetical collapse of civilization, Nuclear War is as engrossing as it is terrifying. It’s also incredibly accessible, acquainting a layman audience with topics otherwise reserved for physics papers and military personnel.

“The joke is that I write for little old ladies in South Dakota and generals at the Pentagon,” Jacobsen tells Big Think. “And sure enough, I have received fan mail from both.” The idea for Nuclear War first came to her during the COVID pandemic while researching the 1918 Spanish flu, a catastrophe so devastating that most people believed it could never happen again — until it did, albeit in a different, far less deadly form. Nuclear war also seemed improbable to many. But decades after the Cold War, world leaders are once again threatening to use weapons that, to quote Christopher Nolan’s 2023 film Oppenheimer, would “start a chain reaction that might destroy the entire world.”

Nuclear War argues that “might” should be replaced with “will.” But despite its morbid fatalism, Jacobsen explains that she wrote the book “to participate in the conservation so that that doesn’t happen.”

The Oppenheimer effect

Many people believe the existence of nuclear weapons is, in a way, a good thing because their apocalyptic power has helped prevent a third world war, thanks to a principle of deterrence called “mutually assured destruction.” Besides, their line of reasoning goes, if humans had it in them to bring about their own destruction, surely they would have done so already in the decades since the obliteration of Hiroshima and Nagasaki — the only cases in which nuclear bombs have been used in combat.

Jacobsen disagrees on both points. “They have prevented world war,” she concedes, “but we are not our grandparents. It’s time to start thinking differently, not in the least because the idea of using nuclear weapons as deterrents emerged at a time when there were only two nuclear-armed nations, the US and USSR. Today, there are nine such nations — 10 if Iran gets the bomb, and that’s 10 too many. Also, just because something hasn’t happened doesn’t mean it can’t happen.”

The success of Nuclear War is perhaps unsurprising, given the popularity of true-crime content and other morbid media. What could be more disturbing than the fact that everything you know and love may be one button-push away from annihilation? What’s more, after a brief hiatus following the collapse of the Soviet Union, nuclear war is back in the news. Between North Korea launching missiles, Donald Trump taunting Kim Jong Un over said missiles, and Vladimir Putin threatening nuclear war should the West involve itself in his ongoing war against Ukraine, many argue the world is as close to Armageddon as it was during the Cuban Missile Crisis — if not closer.

“Quoting the Secretary General of the United Nations,” Jacobsen says, “we are one miscalculation, one misunderstanding away from nuclear annihilation.”

Catastrophic misunderstandings

What might such miscalculations look like? A close call from 1983 offers a glimpse: On September 26, a Soviet lieutenant colonel named Stanislav Petrov received signals from an early-warning system that the U.S. had launched five Minuteman ICBMs (intercontinental ballistic missiles) toward the Soviet Union. Military protocol dictated that Petrov report the supposed incoming attack up the chain of command, a decision that might have sparked a retaliatory attack on the U.S. Stanislav defied protocol, choosing to first verify the warnings. He confirmed it was a false alarm.

Nuclear powers have long used redundancy measures to ensure that launches based on a single signal or the decision of one person are highly unlikely. Still, there’s no guarantee that the U.S. or any nuclear power would be able to accurately distinguish a real attack from a false alarm 100% of the time. But while the world may indeed be “one misunderstanding away from nuclear annihilation,” it’s worth noting that Jacobsen’s book has received criticism for mischaracterizing how the U.S. would likely respond to signals of an impending nuclear attack. In Nuclear War, for example, Jacobsen suggests the U.S. maintains a “Launch on Warning policy.”

“Launch on Warning policy means America will launch its nuclear weapons once its early-warning electronic sensor systems warn of an impending attack,” she writes. “Said differently, if notified of an impending attack, America will not wait and physically absorb a nuclear blow before launching its own nuclear weapons back at whoever was irrational enough to attack the United States.”

The U.S. Department of Defense says it “does not rely on a launch-under-attack policy” but rather maintains the option to prepare and launch nuclear weapons before absorbing a nuclear blow. (Even as an option, this strategy remains debated.)

Cyclical awareness

Despite the threat of nuclear war seemingly growing bigger and bigger with each passing year, it can seem like people in the 21st century aren’t nearly as aware of or concerned with it as previous generations were during the late 1900s.

“I think things go in cycles,” Jacobsen reflects. “One of the reasons so many of these Cold War warriors — scientists and military officers, many in their 80s and 90s — spoke to me for this book is because they felt that the world had forgotten about the threat of nuclear war, even though the threat itself did not go away.”

If awareness of nuclear war is cyclical, we may well be on the cusp of a new age. Sure, schoolchildren don’t conduct nuclear drills as they did during the 1950s and 60s. But the aforementioned stream of nuclear-charged news headlines, not to mention films and shows like Chernobyl and Oppenheimer, are bringing the topic back into view. And while some of these stories — specifically Oppenheimer — have been accused of misrepresenting and fetishizing A-bombs, Jacobsen is happy they exist.

“Any discussion is a good discussion,” she says. “Ignorance is a bad thing. Pretending something isn’t happening is an ostrich approach. Stick your head in the sand, expose your neck — not a good thing. I believe that movies like Oppenheimer add to the conversation enormously, and I’ll give you a direct personal example: I have been to Los Alamos multiple times, and always found the librarians distancing themselves from me, a journalist, as if I was the bad guy, going after something they were trying to conceal.”

“Writing this book was an entirely different experience. This time, the people at Los Alamos were extremely transparent with me, and I was told this was the ‘Oppenheimer effect.’ Not the man, but the movie. The place had been overwhelmed with requests from media and also from individual people wanting to know more, which they embraced and began to, in my opinion, behave more like a public service giving information.”

After years of trying, she even got access to previously classified documents detailing the history and use of the so-called “Nuclear Football,” a briefcase that US presidents can use to communicate with command centers in case of a nuclear attack.

“Mad King” behavior

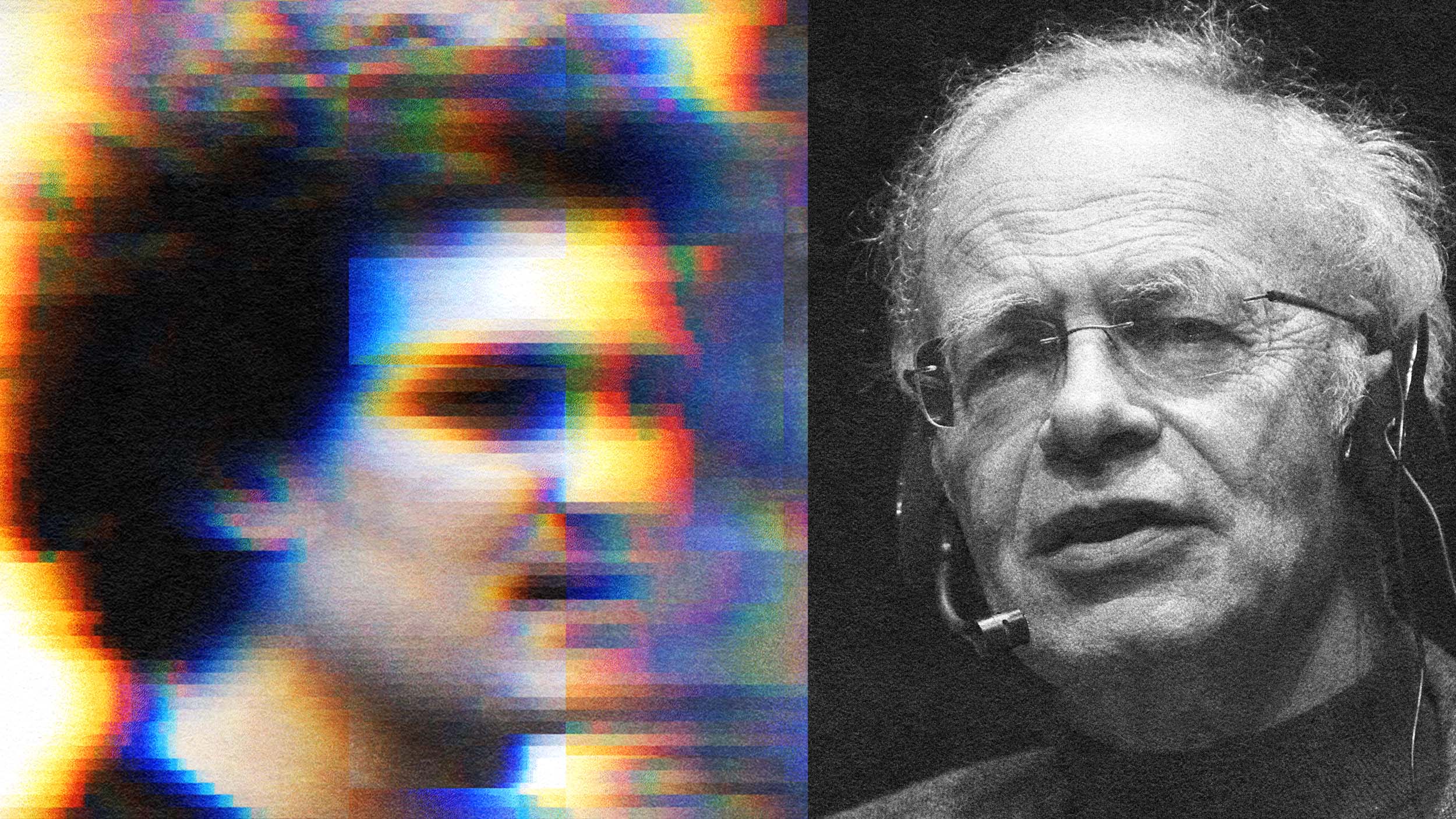

Jacobsen’s book is unique from other texts insofar as she doesn’t focus on why nuclear war happens, but on what it would look like if it happens. Grounding her hypothetical scenario in reality, she asked her interviewees which country or person was most likely to make the first move. Of all the answers, the most memorable one came from Richard Garwin, a physicist whose research led to the creation of the hydrogen bomb — a weapon so powerful it used a nuclear bomb as its detonator.

“You could argue Garwin knows more about nuclear weapons than anyone on the planet,” Jacobsen says. “He has advised every president on nuclear weapons since Eisenhower, and when I asked him about the most plausible scenario, he answered, ‘The Mad King.’”

For fantasy buffs, the word conjures up images of Aerys Targaryen, the unseen archvillain of Game of Thrones who, after failing to defeat a rebellion against the Iron Throne, tries to blow up the royal city of King’s Landing and everyone in it with hidden deposits of green wildfire.

While we like to think of global leaders as being too concerned with their own legacies to usher in nuclear Armageddon, the truth is that on some psychological and even ideological level, self-preservation and world annihilation aren’t mutually exclusive. As Adolf Hitler is thought to have said, “We may be destroyed, but if we are, we shall drag a world with us — a world in flames.” Although the Führer didn’t have the means to bring about an apocalypse in the moments leading up to his defeat, modern-day leaders do. Who’s to say they wouldn’t?

As Garwin told Jacobsen: “Après moi, le deluge. After me, the flood.”

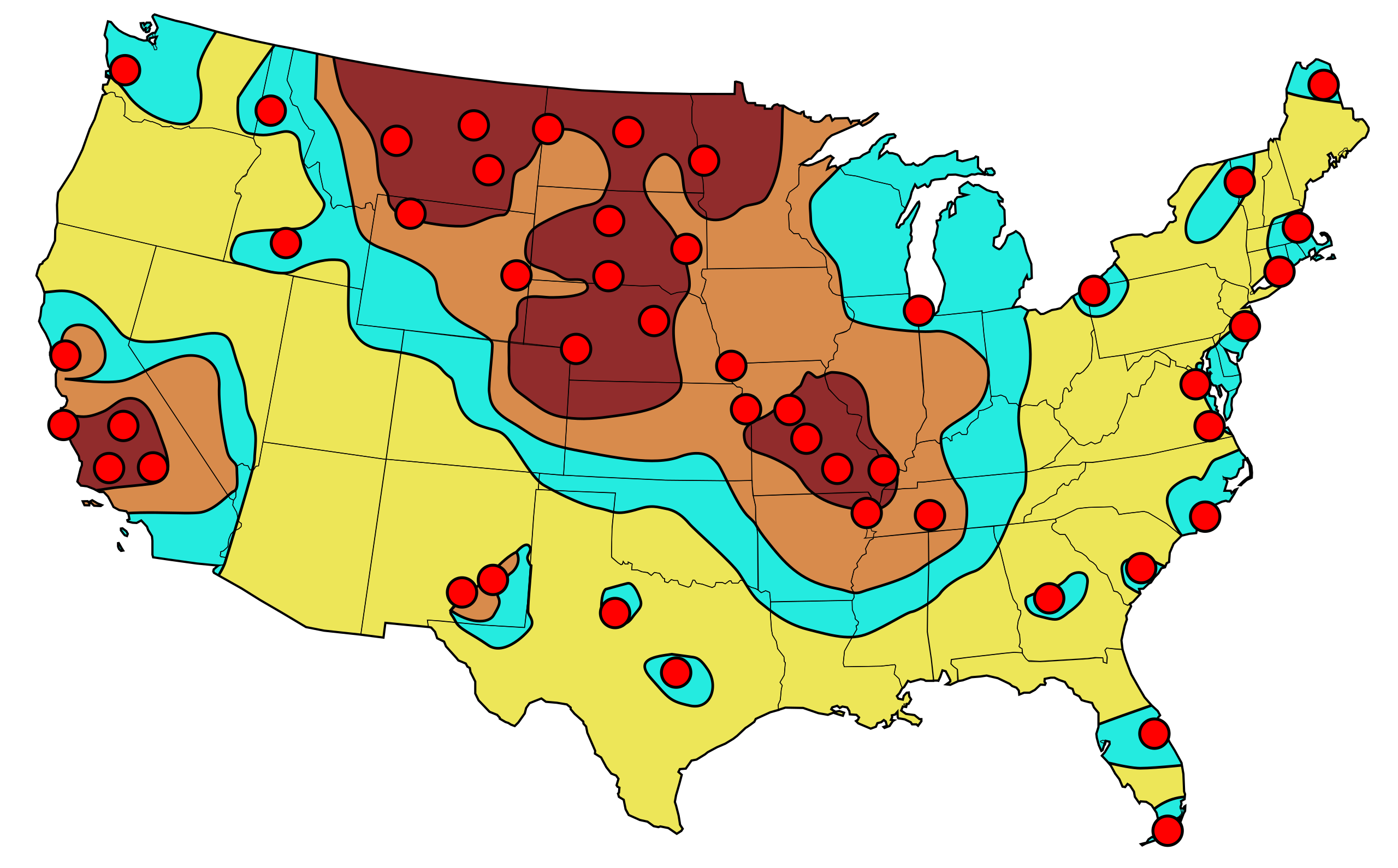

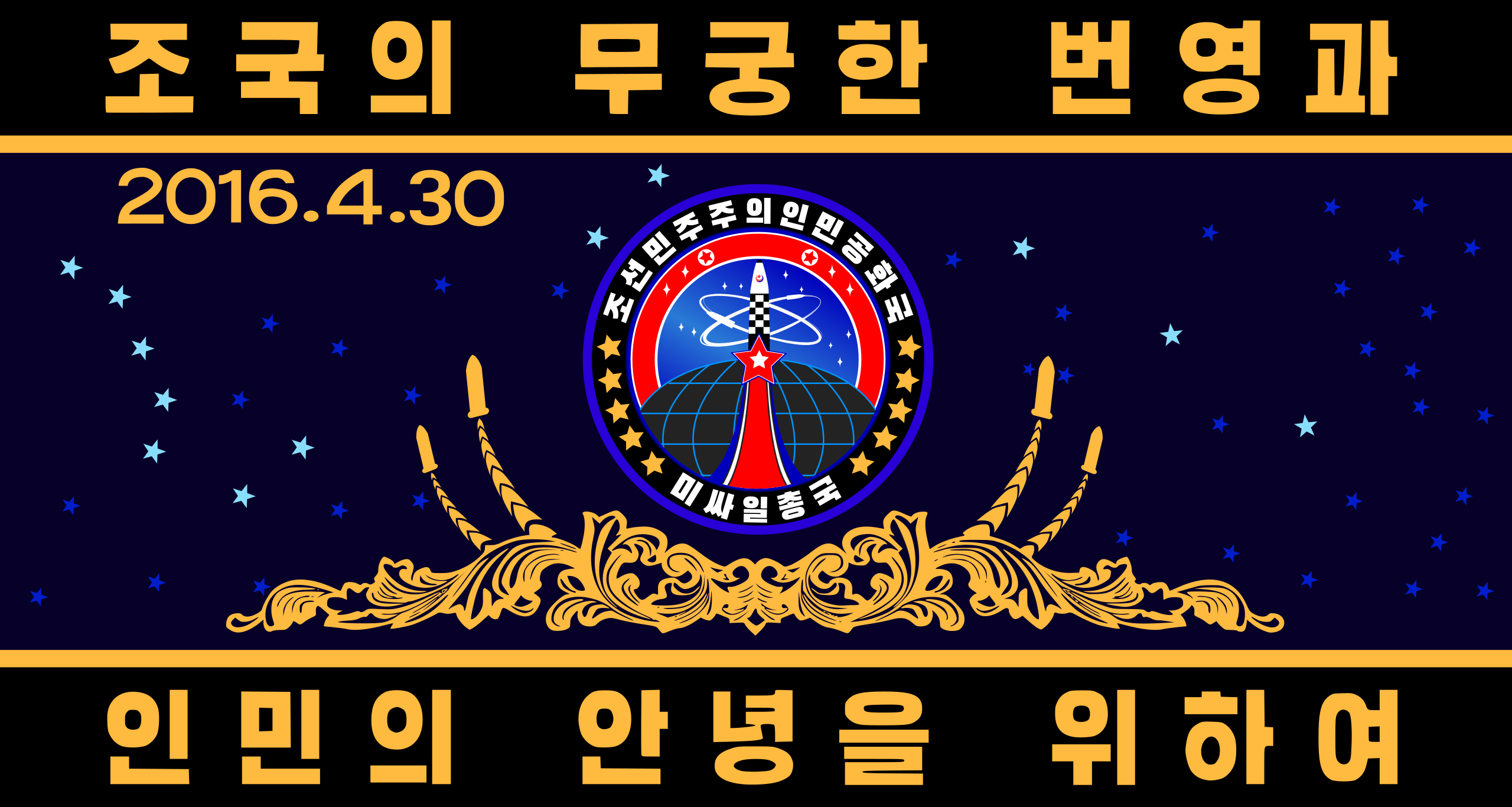

In Nuclear War, Jacobsen interprets Garwin’s “Mad King” to mean North Korea’s Kim Jong Un, and for good reason. “Once nuclear war begins, there are no rules. There are, however, rules to nuclear testing, namely notifying your neighbors so your launch isn’t misconstrued as an attack. During the initial days of the Ukraine War, America postponed a test, as did Russia. North Korea does not do that, and over the course of the 18 months that I was writing the book, the country launched more than 100 missiles without announcing them. That’s ‘Mad King’ behavior.”

The Reagan reversal

As upsetting as Nuclear War is, Jacobsen still believes that nuclear war can be averted — and the road to aversion begins, of all people, with Ronald Reagan.

“There’s a concept called the Reagan reversal, which is the one spark of hope in all of this darkness. Originally, Reagan was a hawk who believed more nuclear weapons would keep America safe. That is, until he watched a TV movie called The Day After. It was a fictional story of what would happen in a nuclear war between the Soviet Union and America. Reagan’s cabinet members did not want him to see it, but he did, and he wrote in his journal that he became greatly depressed. But out of that depression, he took action. He reached out to Mikhail Gorbachev and they set up the Reykjavik Summit. After that, the world went from an all-time high of nuclear weapons in 1986 — 60,000 warheads — to around 12,000 today.”

Another Reagan reversal — brought about through international cooperation spurred by a shared awareness of the reality of nuclear holocaust — could revert the collision course humanity is on today.