NASA medical officer on spending 378 days in a Mars simulation

- Emergency physician Nathan Jones spent 378 days inside a simulated Mars base.

- During this time, the walls never crept in on him; time mostly went by quickly.

- In this interview, Jones reveals how he keeps calm under pressure.

“Hello,” Kelly Haston, commander of NASA’s Crew Health and Performance Exploration Analog (CHAPEA), told the press after she and her crewmates emerged from a 378-day stay inside a habitat designed to simulate the conditions astronauts would face on a mission to the surface of Mars. “It’s actually just so wonderful to be able to say hello to you all.”

No human has yet visited Mars but NASA is planning to change that. Sometime between 2030 and 2040, the agency hopes to commence humanity’s first manned mission to the planet, located a little over 138 million miles from Earth, 145 times farther than the Moon.

The purpose of the 378-day simulation was to get a sense of what kind of challenges astronauts could expect on their way to and on Mars, what kind of equipment and resources they may need, and how the mission would affect the astronauts mentally and physically. To do that, NASA built a 1,700-square-foot, 3D-printed habitat called Mars Dune Alpha in a hangar at NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston.

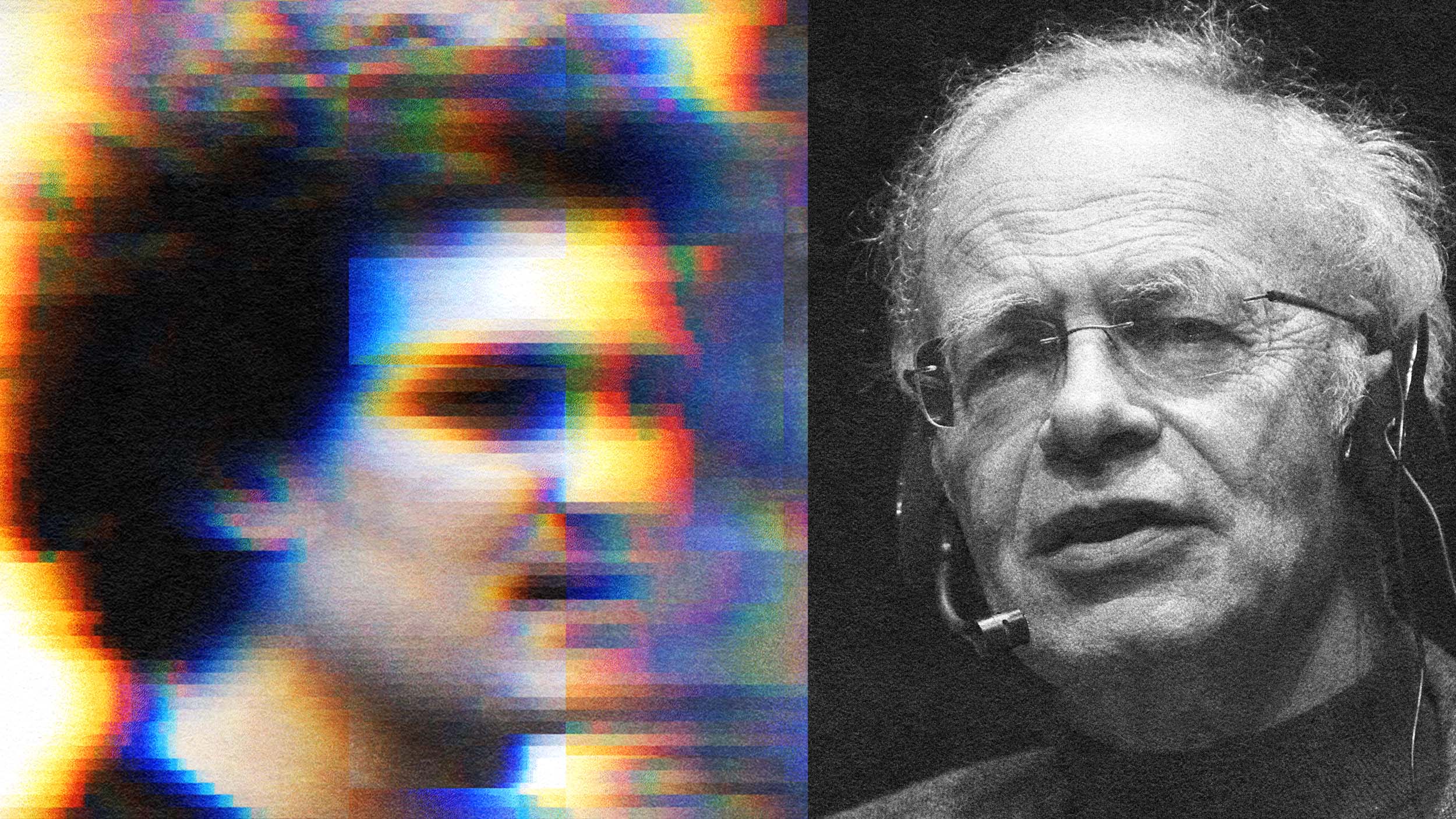

Emerging from the simulation with Haston were: Ross Brockwell, flight engineer; Nathan Jones, medical officer; and Anca Selariu, science officer. Also present were Steve Koerner (NASA Johnson Space Center deputy director), Kjell Lindgren (astronaut and deputy director of Flight Operations with NASA), Grace Douglas (CHAPEA principal investigator), and Julie Kramer White (director of engineering).

Although the crew has largely avoided the press as they spend much-needed time with their families and loved ones, Big Think was able to hop on a Zoom call with Jones, the medical officer. In the following interview, Jones, a seasoned emergency physician and SWAT doctor, reveals what it was like inside the Mars simulation.

Mars walks

“I saw it as a neat opportunity to be part of the science that will get us to Mars and be an integral part of the next giant leap for humanity,” Jones says when asked what motivated him to volunteer for CHAPEA when the project was announced several years ago. Although you would expect his family to protest the decision, they were actually quite accepting. “There were definitely some who thought I was being a bit cavalier,” he said. “But they all got it and knew why I was doing it.”

Believe it or not, participating in a 378-day simulation isn’t the most extreme thing Jones has done in his career as an emergency physician. In addition to working on ambulances and helicopters, Jones has been on several medical missions to distant regions like Central America. He’s also worked as a SWAT doctor, joining the team on dispatches.

In retrospect, Jones’ extensive experience treating people in unusual, unpredictable, and highly stressful situations is precisely why he was selected for the Mars simulation, which requires people who can deal with things that would send others into immediate shock.

“I think part of it’s just practice,” Jones says of how his career has hardened him, “doing things over and over again until you kind of get used to them. When you’re in the emergency room and you have a crashing patient, you’re so used to going through the ABCs. You stick to that and don’t get caught up in the moment, or else bad things are bound to happen.”

Although NASA and other space agencies do their best to select healthy astronauts with minimal histories of medical complications, you never know what can go wrong in outer space. NASA wanted a physician who was not only calm and level-headed but resourceful, too.

“Once, after an international mission trip, I was out in a field with someone and they had a leg injury,” Jones tells Big Think from his home in Springfield, Illinois. “I was able to stitch them closed, without us having to visit the emergency room. Those types of skills would be helpful to a space crew. Split a strained ankle, examine eyes after getting dust in them – that sort of thing.”

During the simulation, NASA researchers carefully observed the amount of resources the crew used. This way, they got a rough idea of how many supplies they would have to pack for an actual mission. While supplies to the International Space Station can be replenished from Earth, a Mars crew would be completely on their own once they leave Earth’s orbit:

“If something goes wrong on Earth, you can deal with it yourself. But if something goes wrong on Mars, you can’t go to the store and buy replacement parts. If we launch an actual mission, we’d probably pre-position supplies there before we arrive.”

When none of his fellow crew members required medical attention — which was the vast majority of the time — Jones would join them in their daily activities. “We’d get up at 6:00 a.m. every day,” he says. “We had about an hour to get ready and eat breakfast. Then, we’d have a morning meet-up and go over the day’s plans.”

These plans ranged from robotics operations and exercises to habitat maintenance and growing crops, not to mention extravehicular activities (EVAs), in which the crew practiced walking across Mars’ surface with space suits and equipment in tow. “In total, we did 100 EVAs, significantly more than all other space missions NASA is involved with,” Jones says. “We also had some allotted time for team activities to get to know each other and make sure we had a strong relationship.”

These teambuilding exercises had another purpose: to avoid the simulation from turning into an episode of the dystopian science fiction show Black Mirror, something that isn’t as unthinkable as it sounds. NASA’s recreation of the Red Planet is immersive, to say the least.

For over a year, the crew’s food intake was limited to the prepackaged, shelf-stable foods they took with them — plus the fruits, vegetables, and herbs they were able to grow inside their mini-greenhouses. Communications with mission control were delayed by 22 minutes, which is the time it would take for radio signals to travel from Earth to Mars and vice versa. (Regrettably, the same applied to the online games of UNO Jones would play with his children).

For the experiment to work, the CHAPEA crew had to act as though they were actually on Mars. This, combined with the simulation’s believability and attention to detail, led to a point where, for certain periods, Jones would almost forget that he was still on Earth.

“NASA did an excellent job setting up the simulation so that it gave us every opportunity to feel like we were actually there,” he says. “People ask me, if you don’t have Mars gravity, then how can it feel like you were actually on Mars? We adapt so quickly to our environments, I think you’d probably notice it for the first couple of weeks, but after that, you’re just going to adapt to the change.”

Surprisingly, he never felt like the walls were creeping up on him. “When you feel the isolation setting in at times, you have to reframe your mindset. One thing I really found valuable is that life seemed to pass by so quickly in the simulation, but then there were these times where everything slowed down. When there wasn’t much going on, I remember just thinking, ‘This is actually kind of great.’”

Leaving the Matrix

In a way, his time inside the simulation functioned as a detox from the digital world. “We were all disconnected for a year and didn’t have our cellphones,” Jones says. “One of the starkest things when we left the simulation was when they gave us our phones back. The buzzing, the blinking, the constant attempts to grab your attention, I still have to get used to that.”

While Jones was getting used to features of everyday life that had become alien to him during his stay at the Mars Alpha Dune, he also caught himself carrying automated behaviors from inside the simulation into the real world. “Even a few days ago, I ate something and a while later went, ‘Oh, my gosh, I forgot to log that,’” he recalls, referring to how, inside the simulation, they had to record everything they ate so NASA could keep a close eye on their biometrics.

Jones suggests the biggest challenge of an actual manned mission to Mars will be the sheer distance between the Red Planet and our own.

“We had a window with a simulated view of Mars and another of Earth,” he recalls, noting that one got slightly bigger while the other got smaller and smaller with each day. “At night, you can look up to the sky, see Mars, and realize how tiny the speck looks from Earth,” a realization brought home by the delays in their communication.

You’d think Jones and his fellow CHAPEA crew would be the ideal candidates for a manned mission, but that’s not necessarily the case. As mentioned, NASA isn’t planning to send people to Mars until the 2030s at the earliest, meaning the CHAPEA crew members, most of whom are already middle-aged, will be too old to board the flight.

“I’m currently in my 40s,” says Jones. “15 or 20 years from now, I’m probably going to be too old, from a health standpoint at least, to be sent on a mission like that. That said, I suspect someone a lot like me is who they’d be looking to pick as their physician.”

Jones ends the interview by saying he’s “handed on the baton. I’ve run my part of the race, and don’t have any current plans to return to space — real or simulated.”