Ian Brooke wants to revolutionize flight as we know it

- Jet engines generate thrust with a fast-moving jet of heated gas but can be inefficient in fuel use.

- Ian Brooke, CEO of Astro Mechanica, is developing a new engine that uses electric motors to drive the fan and combustor independently.

- In this profile, Brooke discusses his dream of building newly designed planes that make air travel more sustainable and practical.

For over two decades, Ian Brooke has wanted to build his very own airplane – one he entirely designed from engine to airfoil. Now, he’s getting that opportunity, and it just so happens that this craft could revolutionize air travel as we know it.

The 34-year-old Brooke is CEO of Astro Mechanica, a Y Combinator-backed startup that has invented a new kind of jet engine. It’s radically more efficient and versatile than anything that has come before.

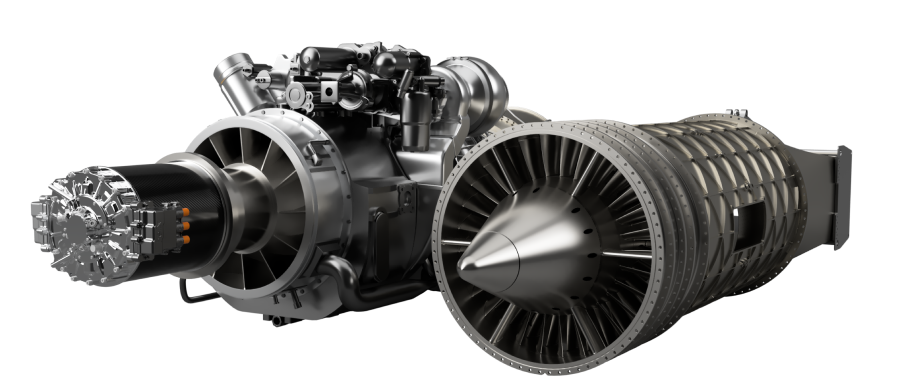

A jet engine is a remarkable machine – generating immense thrust with a fast-moving jet of heated gas. It comes in a few different forms, each differing in fuel efficiency and power. We’ll focus on two of those forms: the turbojet and the turbofan.

First, the turbojet, once widely used in military fighter jets: It’s inefficient, but produces high-velocity thrust. How it works can be famously summarized with four words: “Suck, squeeze, bang, blow.”

Gobs of air enter in the front of a turbojet engine each second, at the physical urging of a compressor fan rotating at several hundred miles per hour. That’s the “suck.” The long fan tapers towards the back as the engine chamber narrows, squeezing the air to vastly higher pressures. The air then enters combustion chambers where fuel is sprayed and the mixture ignited with a “bang”! Gasses form explosively and then expand and “blow” through the back of the engine, providing thrust in the forward direction. As the gasses leave the engine, they pass through another fan-like set of blades, called a turbine, which rotates the shaft that spins the compressor at the front.

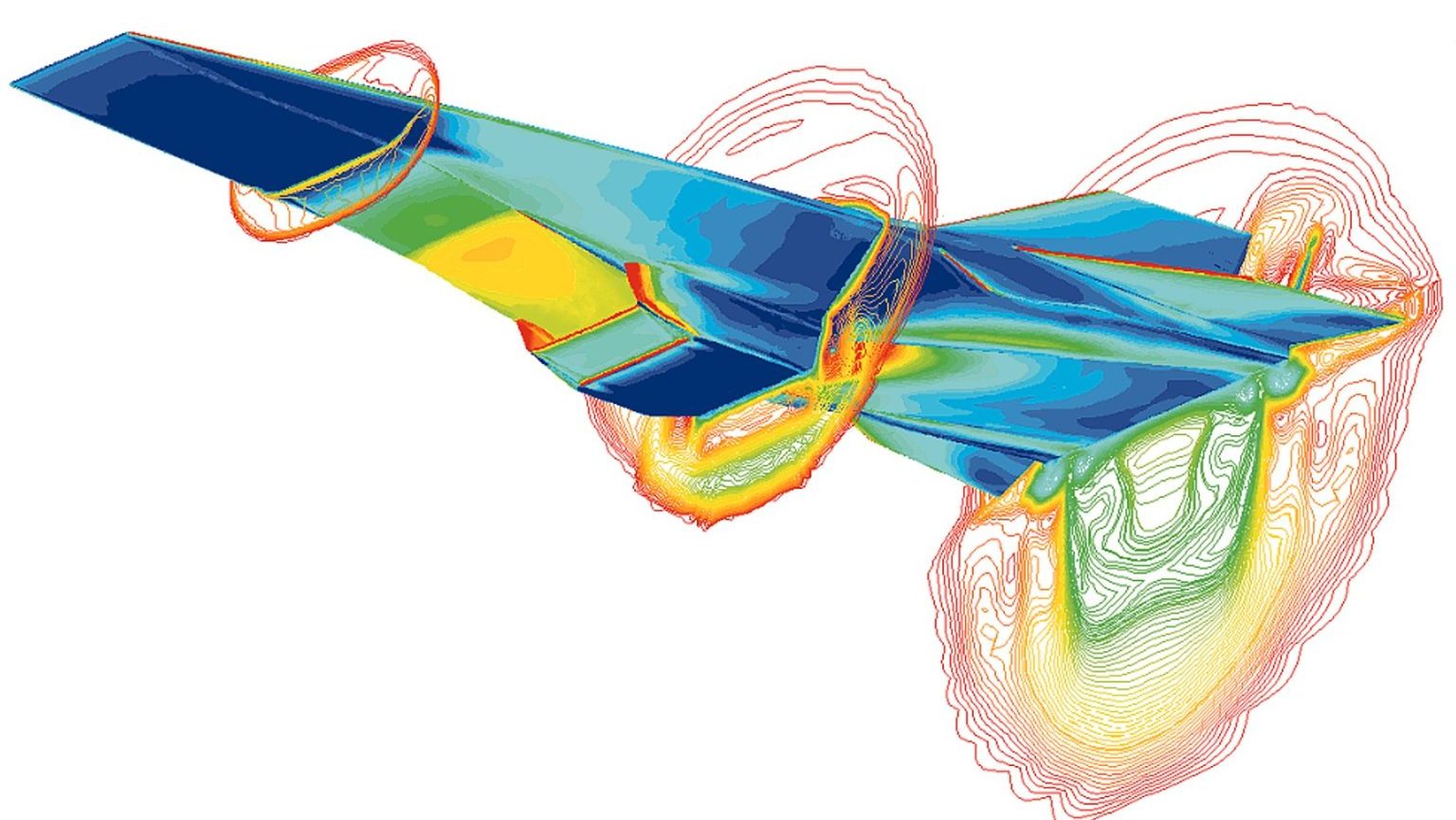

So, that’s a turbojet. A turbofan utilizes what’s essentially a turbojet core to spin a much larger fan at the front of the engine, pulling in a lot more air. Only some of that air is sent through the core, while the vast majority travels around it and exits out the back without combustion, generating thrust more efficiently. Most modern airliners and even fighter jets use turbofan engines because they balance power with fuel efficiency. A turbofan can propel a commercial passenger airplane weighing half a million pounds at speeds of 650 miles per hour, and do that for over half a day with onboard fuel.

Now, what about Brooke and Astro Mechanica’s revolutionary engine?

Their potentially flight-altering idea is to instead use electric motors to separately drive the large fan and the engine’s combustor. That allows these two components to operate independently at whatever speed is optimal, rather than both being directly tied to the turbine core. This is possible now thanks to vast improvements in the size and efficiency of electric motors over the last couple decades, driven by advances in electric vehicles. These electric motors are powered by a turbogenerator, which creates electricity from a spinning turbine.

“The adaptive engine can behave either like a turbofan or a turbojet,” Brooke explained to Freethink. “It uses the electrical power from the turbogenerator to spin a fan. It can then also combust that air in varying increments to adjust how fast the air goes out the back. Between being able to slightly adjust the pressure from the compressor stage, and then hugely varying how much of that air we combust, we can have a thing that is both a pure turbofan and pure turbojet in one.”

The combination of electrical power and adaptability inspired the engine’s name: the Turboelectric Adaptive Engine.

“As you go faster, you only want to push air out the back faster as you’re going faster forward. This is a very simple way to do that,” Brooke said.

He uses a bike analogy to explain his engine’s advance to laypersons. Right now, jet planes are essentially using a higher gear when starting from a dead stop or operating below cruising speeds. They’re doing much more work than they need to, wasting precious fuel.

Astro Mechanica claims the Turboelectric Adaptive Engine will unlock massive efficiency gains across a whole range of speeds, but especially at supersonic speeds between Mach 1.8 to Mach 3.4. The company also intends for their plane and engine to be powered with liquefied natural gas (LNG), rather than conventional jet fuel. Why? Because LNG emits 30% less carbon dioxide than jet fuel and is presently one-tenth the price.

Brooke says that aircraft makers, airports, and engine designers don’t use LNG because it would require a complete redesign of commercial planes and airport infrastructure, at total costs reaching into the tens of billions or more. Considering this entrenched roadblock, he notes that the Turboelectric Adaptive Engine could easily be built to run on jet fuel, as well.

Freethink contacted jet engine experts at various institutions, asking if they could spot any clear red flags with the startup’s pioneering engine and game-changing proposal to utilize LNG. Those who replied said there would be engineering difficulties but didn’t spot any obvious physical limitations. To borrow a phrase, Brooke’s idea just might work.

Rural roots

That idea was born out of the boundless curiosity that Brooke experienced growing up in rural Sonoma County, California. As a youth, the Redwood forests were his playground. He could look up and see the mighty trees stretching high into the air, appearing to touch the sky itself.

“I think it is better to grow up in a rural area, because the only actual laws are the laws of nature,” he told Freethink. “If you grow up in a city, you learn fake human rules. Now they’re good rules to know, maybe useful for navigating society… but a level down from what the actual truth is.”

His family was a “motorcycle family,” Brooke described, recalling how his mom once broke both her arms while popping a wheelie.

“They liked their machines.”

His fundamental aim isn’t to run a wildly successful company and become super rich and famous — it’s to build his dream plane.

So did Brooke. From a tender age, he was enamored with vehicles. At first it was any kind – the faster the better. He soon decided that planes were the coolest kind of vehicle, however, and they quickly became his fixation.

In November 2003, Brooke met an American Airlines captain and aircraft mechanic. The experienced aviator took the bright and curious teenager under his wing, launching a mentorship that still endures today. One of his earliest lessons was teaching Brooke to build better model aircraft.

Brooke assembled planes at first, but model helicopters truly tested his burgeoning engineering skills and his youthful mettle, which he would use to launch his first business in aerial imaging. “They were immensely difficult to fly; they could decapitate you,” he remembered, laughing. “The later ones I built were big enough to truly take your head off.”

By the time he was in high school, Brooke graduated to building real planes with his mentor’s guidance. He was beginning to realize that he wanted to make his very own aerospace company.

This growing sense of purpose crystallized for Brooke when he and his mentor visited an airshow and saw a McDonnell Douglas F-15 Eagle fighter jet up close.

“Wouldn’t you want to fly that?” his mentor asked. Ian did, but he didn’t want to join the military, flying only where and when you were ordered to. He wanted to fly on his terms, in a craft he himself created.

Faster, forward

Roughly two decades later, as CEO of Astro Mechanica, Brooke’s desires remain the same. His fundamental aim isn’t to run a wildly successful company and become super rich and famous — it’s to build his dream plane. Laser-focused on that goal, he doesn’t spend much time building up his own personal brand like other tech entrepreneurs. Brooke rarely tends his social media accounts, only posting eleven times on X in the past year. Moreover, he thinks that entrepreneurs who seem to prefer attention over working on their own projects are not to be trusted.

Brooke’s unflashy style was initially somewhat of an impediment when he first attempted to raise investor money to launch Astro Mechanica. His lack of academic credentials didn’t help, either – there’s no engineering degree, MIT or CalTech background, or famous PhD advisor.

He understood investors’ skepticism. If the roles were flipped, he would be skeptical too.

“Generally speaking, it’s a pretty good filter. I am just this weird outlier.”

Ultimately, though, he thinks outcomes and knowledge speak to expertise more than a stamp of approval from academia. Brooke previously ran a successful company machining motorcycle parts of his own design. And after investors had established aerospace experts vet Brooke and his plan, money poured in.

Brooke has since filled the ranks of Astro Mechanica with engineers who share his “build first, talk later” ethos. The tidy team, numbering less than a dozen, has kept their heads down and delved completely into making Brooke’s engine a reality. They’ve made solid progress, already test-firing two scaled-down engines and planning to publicly demonstrate a full-size model on October 25.

After that, Brooke told Freethink, they’ll spend a year making the engine as light and lean as possible, while designing and building a 20,000-pound plane, essentially a mid-size private jet. Then, at a date yet to be determined, they will affix four Turboelectric Adaptive Engines along with two General Electric CT7 engines to their aircraft and fly it nonstop from San Francisco to Tokyo at supersonic speeds, gathering data the whole way across the Pacific. If that data looks good, then things could really start to get exciting for Astro Mechanica.

Brooke intends to first use this engine to power a mothership that will launch small, satellite-carrying rockets into space, generating significant revenue for the company. (This could sidestep the issues with using LNG as fuel, as well, since the company would be using its own infrastructure.) Next, he envisions the Turboelectric Adaptive Engine will propel supersonic private jets. These would not only be far faster but also cheaper and more sustainable than what’s presently available. At some point down the road, he hopes the engine will make it into commercial airliners, making air travel cheaper and faster for everyone.

Oh, and he wants a couple Turboelectric Adaptive Engines for an aircraft all his own.

“I just want an airplane,” Brooke said.

This article was originally published by our sister site, Freethink.