How will the world end, naturally or by our own hands?

- There is a broad spectrum of threats to civilization, and indeed to human existence itself.

- Over the past decade, threats have changed. The COVID-19 pandemic also gave us a real-time visualization of how we might respond to a greater threat, for better or worse.

- It is a sad reality that the greatest threat to our survival, right now, comes from ourselves.

In 2012, David Darling and I wrote a book called Megacatastrophes!: Nine Strange Ways the World Could End, which for a short time made the bestseller list in the United Kingdom. Over a decade later, public interest in the apocalypse hasn’t abated one bit. (HBO’s The Last of Us is one of the most popular shows on television right now.) So it seems appropriate to reassess the dangers that could end human civilization and to consider which threats David and I might have overlooked or miscalibrated when we wrote our book.

Apocalyptic threats from Earth, Sun, and space

In the book, we used a disaster scale ranging from 0 to 10, with 0 being no problem and 10 equating to total extinction. Although it surprises me now, we gave a relatively low score of 2 to climate change. At the time, we were thinking primarily of a new ice age that would affect agriculture and food production and lead to worldwide starvation. We addressed global warming as well, but more as a natural phenomenon, with increases in the Sun’s luminosity eventually making Earth uninhabitable. Given the continuing release of excess greenhouse gases into the atmosphere, however, this may occur much sooner. Human-induced global warming is already affecting food production and putting plenty of stress on ecosystems. Whether this will result in millions of fatalities is uncertain, but I would set the threat from global climate change at higher than 2 today.

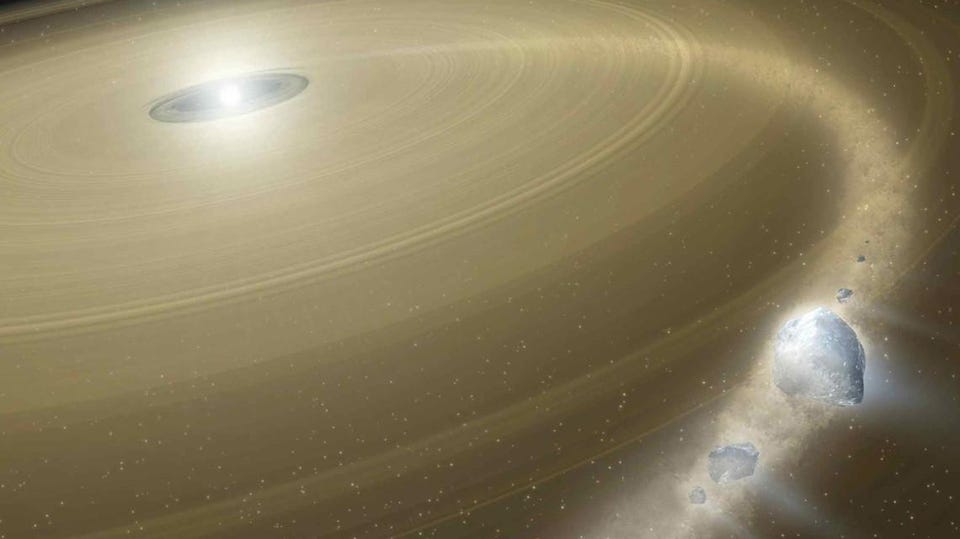

A couple of astronomical threats earned a 3 on our scale. They have a low probability of happening, but total extinction could result if they do. The first is a superflare from our own Sun, and the second is a nearby supernova explosion or gamma-ray burst. As of 2023, there does not appear to be a star near enough to us to pose a big threat, and our Sun seems relatively tranquil, so the odds of such a catastrophe happening soon remain low.

A different kind of space-born danger ranked higher on our disaster scale. We assigned a value of 4 to the possibility of an asteroid impact (moderate probability, with a loss of 10 million or more lives if it occurred). While humanity has made some progress in mitigating this danger, both by keeping a lookout for threatening objects and learning how to deflect them, I would still rate this danger at 4 on our scale, the same score as the natural threat from supervolcanoes. Yellowstone is a stark reminder of that latter threat. Massive outpourings of lava in the northwestern United States 17 million to 14 million years ago, and similar outpourings in the Deccan Traps of west-central India around 60 million years ago, wreaked environmental havoc across the planet.

The potential danger from artificial intelligence, a common worry these days, earned a 5 in our 2012 rankings (moderate probability, with 1 billion or more fatalities). At the time, we were mostly concerned with the possibility of an AI going rogue, a la The Terminator, or of humans becoming so addicted to virtual reality that they lose the ability to function in the organic world. We gave the same rating to nanotechnology, which threatens harmful effects on the human body — or worse still, of turning the world into gray goo.

An alien invasion, one of Hollywood’s favorite disaster scenarios, earned a 6 on the catastrophe meter in our original ranking (moderate probability, with the result of total extinction). If extraterrestrials decided to take over our planet, there is not much we could do to prevent it, since any species capable of interstellar travel would have technology far more advanced than ours. This scenario includes an invasion by alien microbes, which could travel to Earth on our own returning space probes if we are not careful to take planetary protection measures.

Saving us from ourselves

In 2012, our highest-ranked mega-catastrophe, with a value of 7.5, was a pandemic. We considered the probability of this happening to be high, with a casualty count of 1 billion or more depending on the lethality and transmissibility of the plague. Of course, in the years since we have experienced this exact scenario. And while COVID-19 was not as bad as some of history’s previous plagues, it was still a global event. The death count is staggeringly high, and it continues to climb.

The pandemic raises an important question: While advances in technology might prevent some of these disasters, will the worst aspects of human nature get in the way? The global response to the pandemic was impressive in many ways. Billions of people dutifully masked up to protect vulnerable populations and took vaccines that were developed with unprecedented speed. But misinformation, political disputes, and economic inequality detracted from the quality of our response. We will face the same sociological and behavioral barriers when we confront other threats. Indeed, we still cannot say whether society can muster a rational, coordinated response to climate change, or whether we will end up fighting over diminishing resources in a failing biosphere.

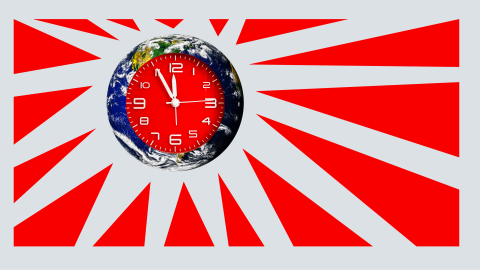

That last point leads us, sadly, to a mega-catastrophe that, if it happens, would be entirely self-inflicted. David and I did not foresee what I now consider the highest existential risk of all, with millions or billions of possible fatalities: an all-out nuclear war. The current war in Ukraine brings the threat home with sobering urgency. A large-scale nuclear war would likely result in a nuclear winter, with all its associated misery. It might not spell the end of humanity, but the number of fatalities from a nuclear war and the climatic changes it induces would probably be in the billions.

I, therefore, assign it an 8 on the catastrophe meter (probability high, with 1 billion or more fatalities). I hope I am wrong. I hope humanity comes to its senses, and that we turn our attention instead to preventing other possible mega-catastrophes that, thanks to the evolution of human ingenuity, we might finally be able to do something about.