The mystery material that can survive 75 nuclear blasts

(Miodownik/BBC Reel)

- A professional hairdresser and amateur chemist invented an unbelievably heat-resistant coating called Starlite.

- Military applications brought governments running, but the inventor’s odd negotiating style ruined discussions.

- Was Starlite lost when he died, or had it already been stolen?

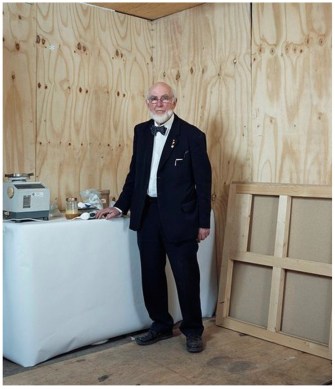

Maurice Ward was a ladies hairdresser and amateur chemist from Hartlepool, Yorkshire, England, and in 1986 he invented a startling plastic coating he called Starlite. Demonstrated on BBC’s Tomorrow’s World in 1990, Starlite was immediately recognized as a game-changing substance scientists and military personnel had been dreaming of: A material so heat-resistant that it could provide a shield from the heat of nuclear blasts. Up to 75 nuclear blasts, according to Ward. Convinced Starlite could make him rich — and paranoid about his ability protect his formula — Ward never patented his invention so as to avoid publishing its secrets. Alas, however, Ward proved impossible to negotiate with, continually changing his asking price and being extremely difficult about loaning samples for testing. The governmental agencies and industries that rushed to acquire the rights and formula for his mysterious invention all failed, ultimately taking with them the massive payday Ward anticipated. Ward died in 2011.

Starlite’s introduction to the world

On that long-ago Tomorrow’s World episode, a Starlite-coated egg was subjected to a ridiculous amount of heat and, though it became charred, it was eventually cracked open to reveal a completely pristine yolk utterly unaffected by exposure to heat. BBC has recently released a set of videos about Starlite, reported by Lee Johnson, called Searching for Starlite. The first segment includes a clip of the material’s momentous debut and talks a bit about Starlite’s eccentric inventor.

Maurice Ward

Stumbling into Starlite

Ward’s daughter, Nicky Ward McDermott, says Ward got involved with scientific experiments at home as part of his work producing his successful and unique line of women’s wigs.

He’d begun working on Starlite in response to the British Airtours Flight 28M air tragedy in 1985. Many of its 55 victims had been trapped in a burning wreckage, and Ward started experimenting with heat-resistant compounds, setting test fires in his back yard to try them out. At some point, he noticed one mixture that just wouldn’t burn and he refined it further into a material able to withstand temperatures of 10,000 degrees Celsius without burning, melting, or producing toxic fumes of the sort that proved so lethal onboard Flight 28M.

Ward’s claims for Starlite were impressive and subsequently verified in tests:

- Cables coated in Starlite were unbothered by heats of 10,000° Celsius — about the same as a nuclear blast — when tested by the British Atomic Weapons Establishment (AWE)

- Starlite-lined eggs were unharmed by the equivalent of nuclear flash and a full-scale explosion when tested by NASA at White Sands New Mexico.

- The UK Royal Signals and Radar Establishment found it impervious to lasers.

As retired British Ministry of Defence scientific officer Keith Lewis is careful to specify to the BBC, Starlite’s strength is against heat, non concussion. In other words, it would have no issues with the heat from a nuclear blast, but an object it protects could still be blown apart by the explosion’s force.

(Miodownik/BBC Reel)

How Starlite worked

Ward was understandably cagey about exactly what comprises Starlite, though he did say it was a mixture of 21 polymers and copolymers along with some ceramic material.

When struck with heat, Starlite chars and instantly produces a carbon foam that pushes forward toward the heat source. This low-density foam is made of an extremely high-melting point material. Heat is then pushed away from the coated object’s surface, and the greater the heat, the thicker the foam layer. “It’s a kind of magical material. It’s a thin paint, but then it becomes quite a thick, chunky insulating material,” says materials and scientist and engineer Mark Miodownik to the BBC.

StarliteTechnologies

Starlite today

At least as recently as of 2013, Ward’s daughter, Ward McDermott, in partnership with her late father’s associate Chris Bennett, operated Starlite Technologies. With a “.org.” — that is, non-profit — internet address, they promoted Starlite for use in firefighting, and secondarily in aviation, home protection, space, and the oil and gas industry — Ward senior had offered to help out in response to the BP Deepwater oil spill in 2010. The largest section of the site is devoted to an exhaustive history of Starlite’s travails, replete with documentation of inquiries, partnerships, conspiracies, partnerships gone bad, lost life-saving opportunities, and proposals left unexplored. (The site’s pages don’t seem to have been updated in the last five years, though there’s a note saying it’s in the process of being re-designed.)

For now, whatever it is that Starlite really is must remain a bit of a mystery, as is the question of whether or not the aerospace industry and military organizations have quietly continued to work with Ward’s invention.