We’ll soon be able to download knowledge from the cloud — by thought alone

Photo credit: Štefan Štefančík on Unsplash

- In a new paper, 12 international researchers claim that an “internet of thoughts” might be mere decades away.

- By utilizing neuralnanorobotics, humans will be able to download information from the cloud by thought alone.

- Potential applications in medicine and education make this a promising endeavor, though the consequences are uncertain.

In a new paper, published in Frontiers in Neuroscience, nanotechnology scientist Robert Freitas predicts that an “internet of thoughts” is a few decades away. The paper, co-written by a dozen international collaborators, states that this fast-tracking of digital technology will enable humans to download information from the cloud by thought alone.

The human brain/cloud interface (B/CI) is based on the work of the splendidly-named “neuralnanorobotics.” In this telling of a utopian future, the tech will allow for the diagnoses and treatment of hundreds of brain diseases thanks to three species of neuralnanorobotics.

The researchers speculate that these tiny critters will break through the Brain-Blood Barrier — it protects our nervous system from fatal bacteria and pathogens — enter the promised land of the brain parenchyma, and “autoposition themselves at the axon initial segments of neurons (endoneurobots), within glial cells (gliabots), and in intimate proximity to synapses (synaptobots).”

Upon plugging into the Matrix, individuals will easily navigate the entirety of “cumulative human knowledge.” A truly personalized Google isn’t the only feature. Other applications include an education upgrade and sweet deals on travel. Well, sort of.

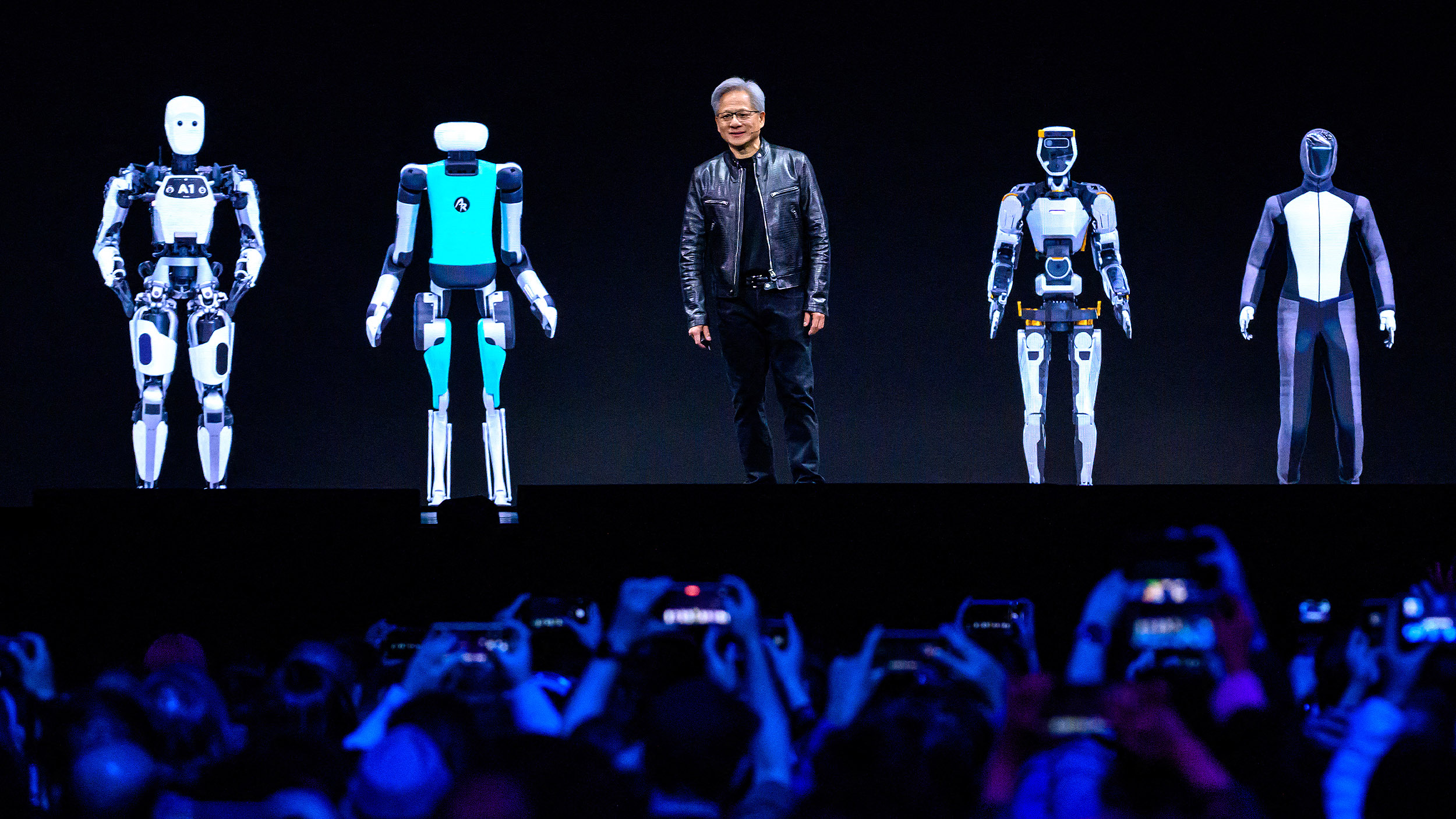

Ray Kurzweil: Get ready for hybrid thinking

Don’t misunderstand: this is a fascinating and important technology. Take Parkinson’s disease, a progressive neurological ailment that results from a lack of dopamine-producing neurons. More than 10 million people suffer this tragic fate, which completely undermines motor control, resulting in rigid muscles, loss of autonomic functions, and severely limited speech and writing. A nanorobot that can identify and even fix this problem would be a breakthrough application.

The implementation of this technology will require a brain-machine interface (BMI), at least during its initial phases. Similar devices currently in the market include prosthetics that link artificial limbs with peripheral nerves. The team imagines a minimally invasive surgery to implant neuralnanorobotics — massively distributed or regionally specific, to be determined. Cloud computing power will also need an upgrade to handle the massive load of distributed information.

Philosophizing over medicine is one thing. We simply can’t imagine this without hitches, and not only Google Glass-level failure. For example, I’m certain that Oculus, incredible as it currently is, will soon feel clunky, with its heavy headset and vest. One day the VR tech will only require glasses, or eyeshades, along with pair of sound pods that might also transmit vibrations down our spine to mimic video game bullets. Eventually contact lenses, then implants. Our virtual and augmented realities will be seamless.

Oculus, like this internet of thoughts, also features educational aspects. The team is championing new forms of learning. Recently I Oculused around my old college campus — in Google Maps — observing vast infrastructure upgrades since my time there. Perhaps in another decade or three I’ll enter classrooms and download entire books directly to my cortex. Another boon.

But let’s be realistic. Goldman Sachs estimates that virtual- and augmented-reality retail operations will fetch $1.6 billion by 2025. That’s well before the neuralnanorobotics invade our parenchyma. Will anyone take advantage of this direct connection between cortex and cloud? Mark Zuckerberg infamously covers his laptop camera to protect himself from himself. Can we really expect that gliabots will be equipped with proverbial duct tape to shield our data from companies interested in our purchasing habits, political inclinations, sexual deviations, drugs of choice, and everything else about us?

Ray Kurzweil speaks at The SXSW Facebook Live Studio, March 13, 2018 in Austin, Texas. (Photo by Travis P Ball/Getty Images for SXSW)

As fascinating as Oculus is, it’s also disorienting. It takes me a few post-headset moments to integrate back into Reality 1.0. The researchers of the new study believe this sort of disassociation to be a feature.

“Fully immersive virtual reality may become indistinguishable from reality with the emergence of neuralnanorobotics, rendering many forms of physical travel obsolete. Office buildings might be replaced by virtual-reality (VR) environments in which conferences could be attended virtually, replacing today’s VoIP conference calls and Internet-based video conference calls with highly realistic, fully immersive VR conferences in virtual-reality spaces.”

Which is where a snowflake turns into the avalanche. Our sense of self is inextricably entwined with our environment. As our relationship to what we used to call “the environment” shifts to screens and headsets, disorientation will deepen. Our mental maps of our bodies navigating the surroundings — proprioception and exteroception — will become relatively obsolete. This imagination upgrade will come at a cost: the ability to control our bodies moving through space. Take a walk down any street in America and observe people walking around staring at their phones for a preview.

Despite the metaphysics of futurism, we still need our bodies. We need the planet too. As science writer, Feriss Jabr, wrote yesterday in celebration of Earth Day,

“Like many living creatures, Earth has a highly organized structure, a membrane and daily rhythms; it consumes, stores and transforms energy; and if asteroid-hitching microbes or space-faring humans colonize other worlds, who is to say that planets are not capable of procreation?”

Humans might be, as Jabr writes, “the brain of the planet,” yet we do not comprise the entire nervous system. We remain dependent on the shaking and belching and raining planet that birthed us. Our obsessive pursuit of utopia, technological or otherwise, has never worked well. There’s no sign it ever will, regardless of how clever our hubris causes us to be.

The authors of the paper call out our “biologically constrained cognitive abilities,” portending a “safe, robust, stable, secure, and continuous real-time interface system” between our cortex and the cloud. Yet we’ve had this interface for eons. “Primitive” minds called it stargazing.

The entirety of human knowledge doesn’t count for much if you never leave your pod. “Rendering many forms of physical travel obsolete” doesn’t sound like much of an upgrade for a nomadic ape that fell in love with itself just a little too much. It sounds, in fact, like a marketing promise to an animal that willingly surrendered motor control in the incessant and crazed search for another dopamine hit.

—

Stay in touch with Derek on Twitter and Facebook.