Airspeeder’s ‘flying car’ racers to be shielded by virtual force-fields

Credit: Airspeeder

- Airspeeder is a company that aims to put on high-speed races featuring electric flying vehicles.

- The so-called Speeders are able to fly at speeds of up to 120 mph.

- The motorsport aims to help advance the electric vertical take-off and landing (eVTOL) sector, which could usher in the age of air taxis.

Airspeeder, the world’s newest motorsport, is set to debut its first race in 2021.

What can you expect to see? Something like a mix between Red Bull’s air racing and the pod-racing scenes from “Star Wars: The Phantom Menace” — manned electric cars flying close together in the desert at 120 mph, nose-diving off cliffs, and racing over lakes, all while hopefully avoiding collisions.

Airspeeder calls its vehicles flying electric cars, but it’s probably easier to think of the wheelless multicopters as car-sized drones. Powered by electric batteries, the carbon-fiber craft use eight propellers to fly, and the tiltable motors are designed to allow pilots to navigate through the course’s pylons at high speeds.

Credit: Airspeeder

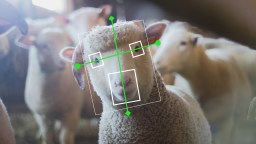

To prevent crashes, Airspeeder is working with the companies Acronis and Teknov8 to develop “high-speed collision avoidance” systems for its Speeders.

“As they compete, Speeders will utilise cutting-edge LiDAR and Machine Vision technology to ensure close but safe racing, with defined and digitally governed no-fly areas surrounding spectators and officials,” Airspeeder wrote in a blog post.

Credit: Airspeeder

Beyond motorsports, Airspeeder hopes to help advance the electric vertical take-off and landing (eVTOL) sector. This sector is where companies like Uber, Hyundai, and Airbus are working to develop air taxis, which could someday take the ridesharing industry into the skies. By 2040, the autonomous urban aircraft industry could be worth $1.5 trillion, according to a 2019 report from Morgan Stanley.

Still, many technical and regulatory hurdles remain. Matt Pearson, Airspeeder’s founder and CEO, thinks the futuristic motorsport will help to not only speed up that process, but also pave the way for self-driving cars.

Airspeeder TV: Up to Speed – Additional flight footageyoutu.be

“Even with autonomous vehicles on the ground, it’s a difficult thing to get right because computers have to make decisions very fast,” Airspeeder’s founder and CEO, Matt Pearson, told GQ.” But in a racing environment, you have a pretty controlled course and you have the ability to make all the vehicles cooperate with each other. You have a whole load of vehicles talking to each other, so if there’s an incident or a pilot slows down or there’s a traffic jam on the course they’re all aware of each other. This is something we think will revolutionise autonomous vehicles on the ground. It’s technology that will make flying cars a reality in our cities in the future.”

Airspeeder has yet to announce a date for the first race, but Pearson said he hopes to put on three races over the first season. The company is developing two courses: one in California’s Mojave Desert, and one near Coober Pedy in South Australia.