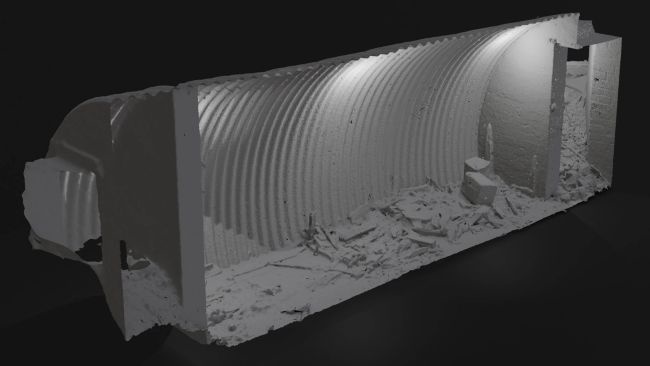

wwii

Winston Churchill had a secret army, and bunkers like this would have hidden them during a German invasion.

In 1905, Albert Einstein’s mother thought he was a genius, his sister thought he was a genius, his father thought he was a genius – but that was about it, says author David Bodanis.

▸

5 min

—

with