sociology

The nation-state had a good run, but its usefulness may have come to an end.

The cognitive scientist argues the current AI environment is failing us as consumers and a society. But it’s not too late to change course.

A survey of more than 6,000 of the world’s richest, most influential people shows that 9% of them attended Harvard University.

In 2021, residents of the top America could expect to live 20.4 years longer than residents of the bottom America.

“The evolution of digital media makes stricter regulation of online behavior not only feasible but inevitable,” writes media ecologist Andrey Mir.

From tribal hunts to Stonehenge and into the modern day, the peer instinct helps humans coordinate their efforts and learning.

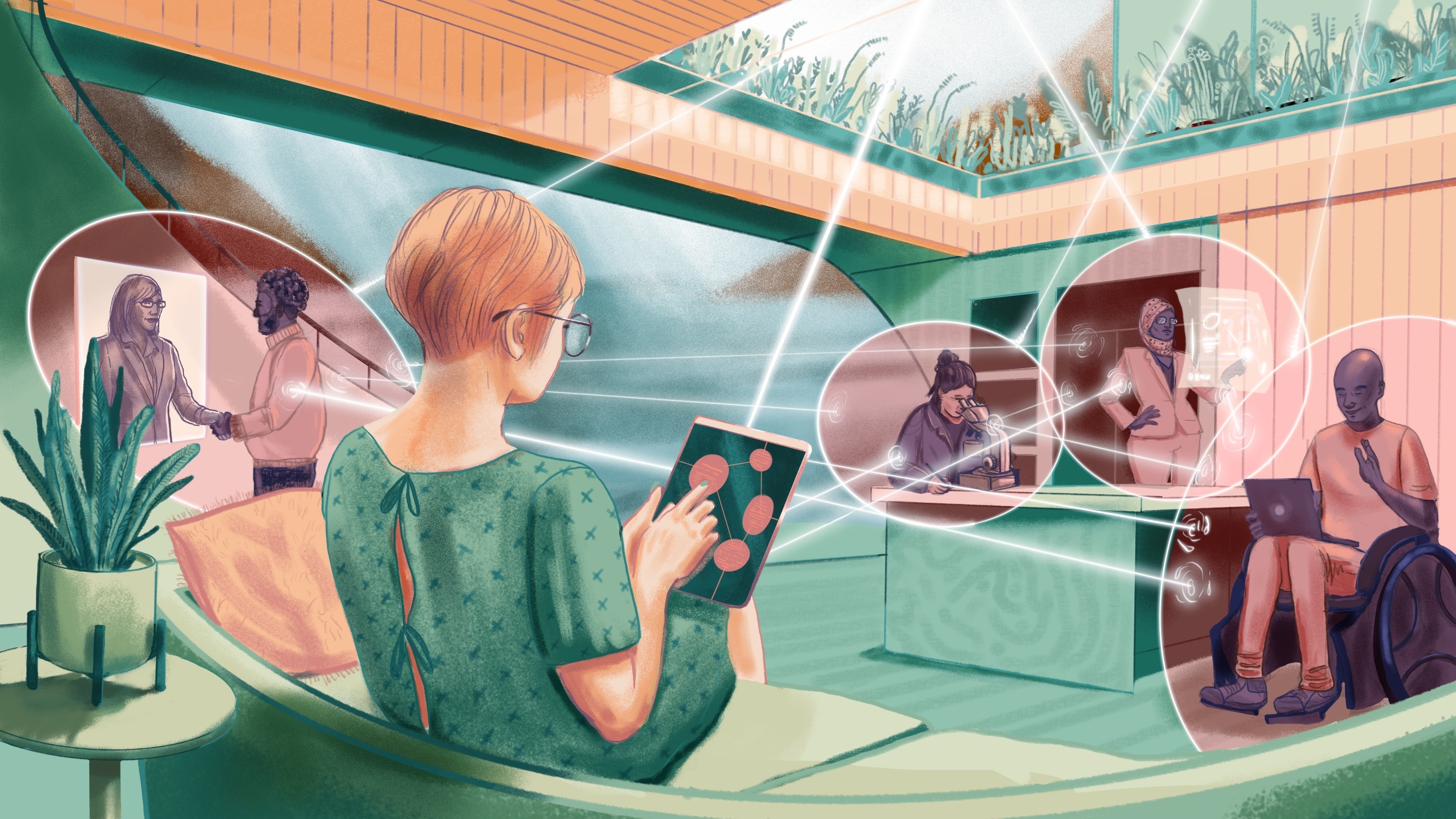

Studying why innovation clusters form can shed light on how to better promote research and growth.

“The primary way that people make friends is through institutions.”

Man seeking meaningful relationship at the intersection of on-demand empathy and Rule 34.

Plenty of parents feel guilty about wanting to skip playtime, but there’s no need.

The electoral reform also known as instant-runoff voting promises bridge-building and broad appeal instead of culture war and gridlock.

The annual rite of passage has always been more about the ambivalence of adults than the amusement of children.

Famed activist Bayard Rustin constantly faced the dilemma of coordinating collective pursuits among diverse groups of people.

In a world of rising cynicism, a celebration of our capacity to create, adapt, and thrive.

How “Catastrophe and Social Change” (1920) became the first systematic analysis of human behavior in a disaster.

What are we supposed to do when experts look at the same data yet reach starkly different conclusions?

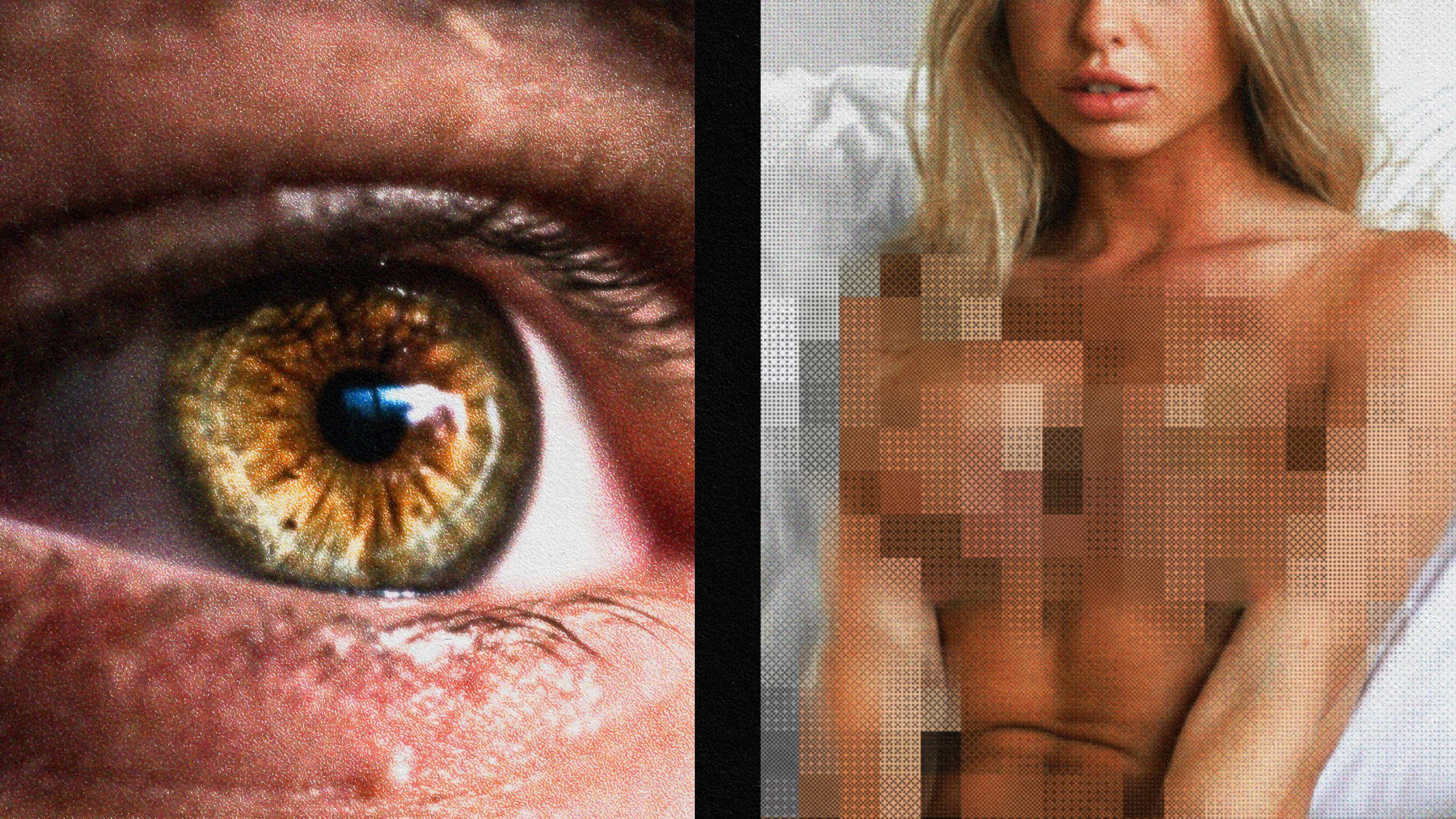

Everyone has to learn about sex somehow. Today, billions of people are learning about it from porn.

And, more importantly, what’s being done to get them online?

In “Not Born Yesterday,” author and cognitive scientist Hugo Mercier makes the case that misinformation is overrated — and other human foibles are underrated.

Mental health awareness is more widespread than ever. Some professionals think it may have gone overboard — especially on TikTok.

Are fava beans and chianti really the best pairing for human liver?

Female physicians tend to practice medicine as it should be practiced: with care and compassion.

The “Shopping Cart Litmus Test” is a popular meme about morality. What does it really reveal about one’s character?

The Human Chronome Project finds that the average human sleeps for 9 hours but only works for 2.6 hours.

“Values emphasizing tolerance and self-expression have diverged most sharply, especially between high-income Western countries and the rest of the world.”

The majority of people in every country support action on climate, but the public consistently underestimates this share.

In the murder trial of Dan White, the defense touched on diet as a cause for White’s actions. It has become known as the “Twinkie defense.”

Public mass shooters almost always have worldviews shaped by the “3 Rs”: rage, resentment, and revenge.

A physicist, a psychologist, and a philosopher walk into a bar and discuss a framework for thinking better in the 21st century.

Susannah Fox, former chief technology officer for the HHS, explains how technology has empowered us to help fill in the cracks of the healthcare system.