Social media

Mark Weinstein outlines a new path for social media that protects, respects, and empowers the regular users.

The digital world will always entail risks for teens, but that doesn’t mean parents aren’t without recourse.

Some news is slow, some news is fast — and there are two simple techniques to help you filter both.

What you can learn about media by parodying it from the print era into the digital age.

TikTok and its allies won’t go down without a legal fight.

Mental health awareness is more widespread than ever. Some professionals think it may have gone overboard — especially on TikTok.

Should social media platforms have the right to decide what speech to allow online? Should the government?

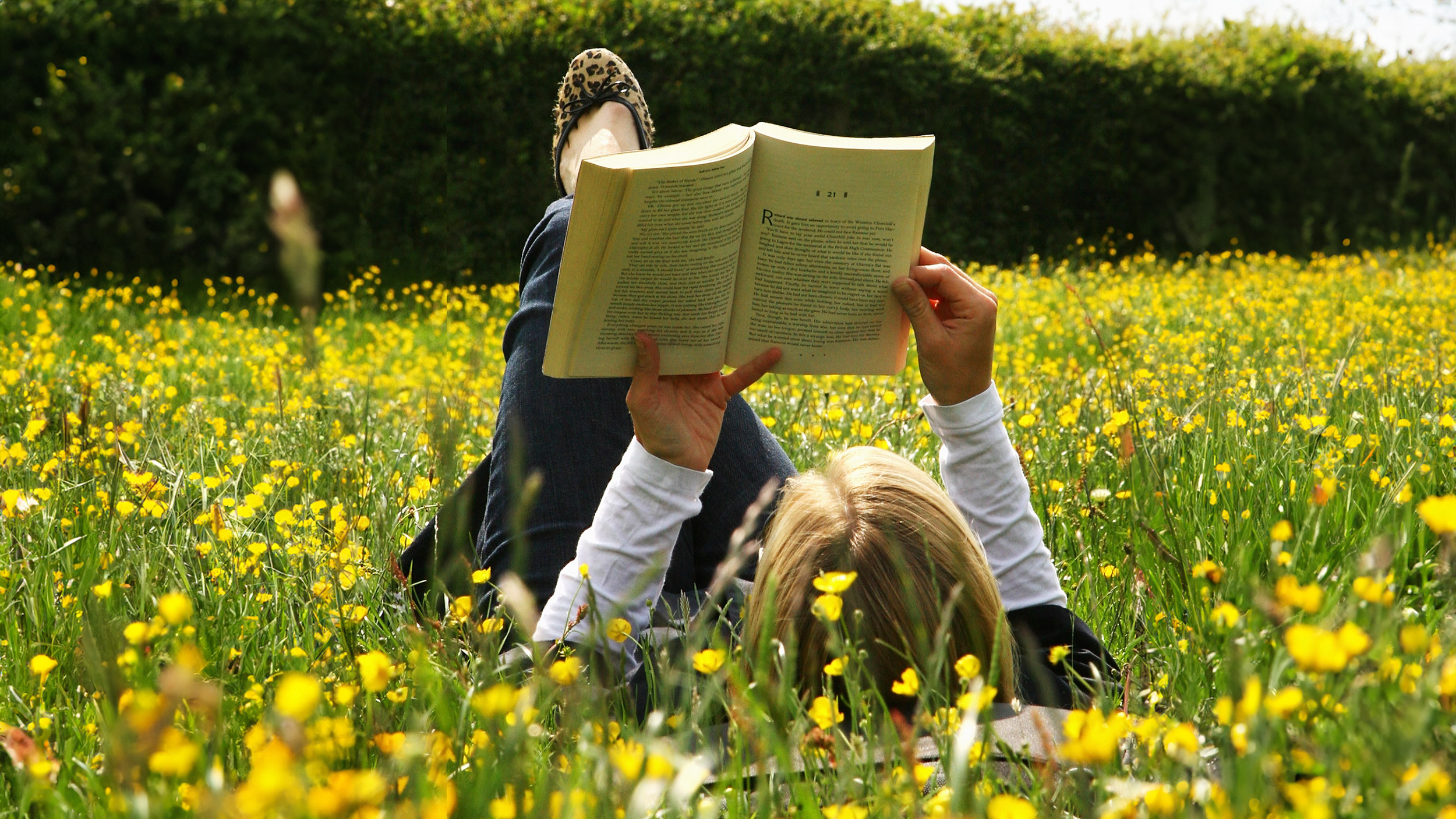

From Hogwarts to hashtags, kids’ reading habits have changed drastically in recent decades — but data suggests cause for hope.

You can learn an awful lot about people, culture, and politics by studying R.

The outrage machine is fueled by toxicity. But there are practical steps that we can take to recapture control over our emotions.

Since 2012, the amount of time that teenagers spend socializing in person has plummeted. Is it a coincidence that depression is more common?

A new online religion is spreading misinformation and phony products.

Self-help gurus for the digital age.

Research shows that spending more time on social media is associated with body image issues in boys and young men.

Telegrams were the “Twitter of the 1850s and 1860s” — and they elicited the exact same overblown fears as Twitter does today.

If you lost your religion, it might be because the internet and social media are having a secularizing effect on American society.

When boredom creeps in, many of us turn to social media. But that may be preventing us from reaching a transformative level of boredom.

People naturally judge fact from fiction in offline social settings, so why is it so hard online?

Brown noise, the better-known white noise, and even pink noise are all sonic hues.

By exposing people to small doses of misinformation and encouraging them to develop resistance strategies, “prebunking” can fight fake news.

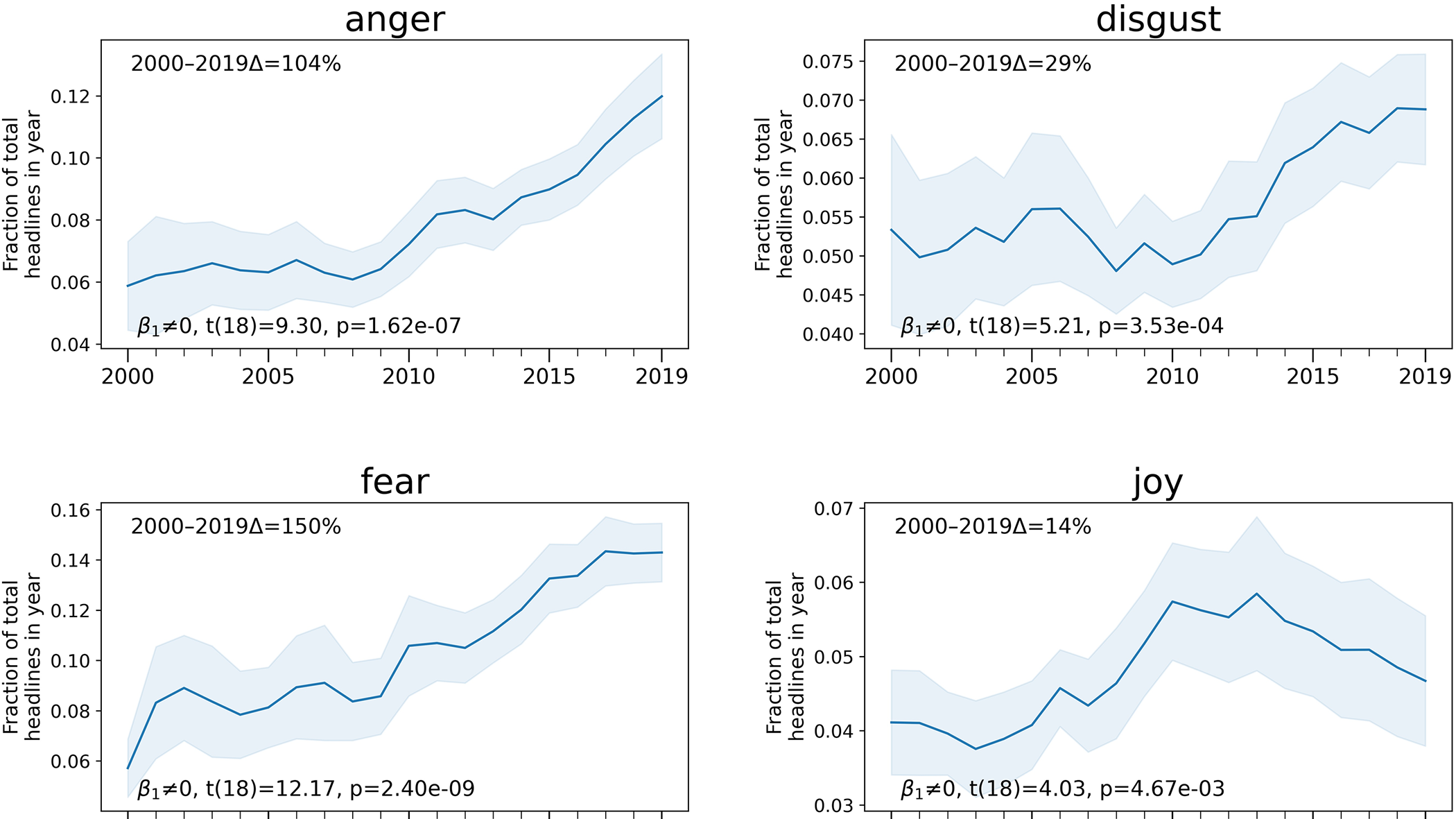

The media is deliberately pushing your buttons.

What responsibility do social media companies like Twitter have to free speech? It depends on whether they are “landlords” or “publishers.”

Elon Musk’s successful bid to take over Twitter has fragmented the internet along predictably partisan lines. But only time will tell whether this is a good or bad thing.

Moral dilemmas reveal the limitations of ethical principles. Oddly, the most principled belief system might not have any principles at all.

Social media distorts the reality of the public sphere.

Outrage is a useful emotion that helped our ancient ancestors survive. Today, it leaves us feeling angry, tired, powerless, and miserable.

Step one, start with a trial separation.

In “Off the Edge”, journalist Kelly Weill dives down the strange rabbit hole of the flat-Earther community.