psychology

New research is uncovering why we eat first with our expectations.

From King Midas to Gordon Gekko, humanity has struggled to grasp greed’s true nature.

Welcome to The Nightcrawler — a weekly newsletter from Eric Markowitz covering tech, innovation, and long-term thinking.

Can we learn to always look on the bright side of life?

“Okay, dad, but GMOs help feed the world.”

Welcome to The Nightcrawler — a weekly newsletter from Eric Markowitz covering tech, innovation, and long-term thinking.

The biases that shape our understanding of the mind.

Why the advertising legend — and author of Alchemy — believes that inefficiency can be genius and insects can unlock innovation.

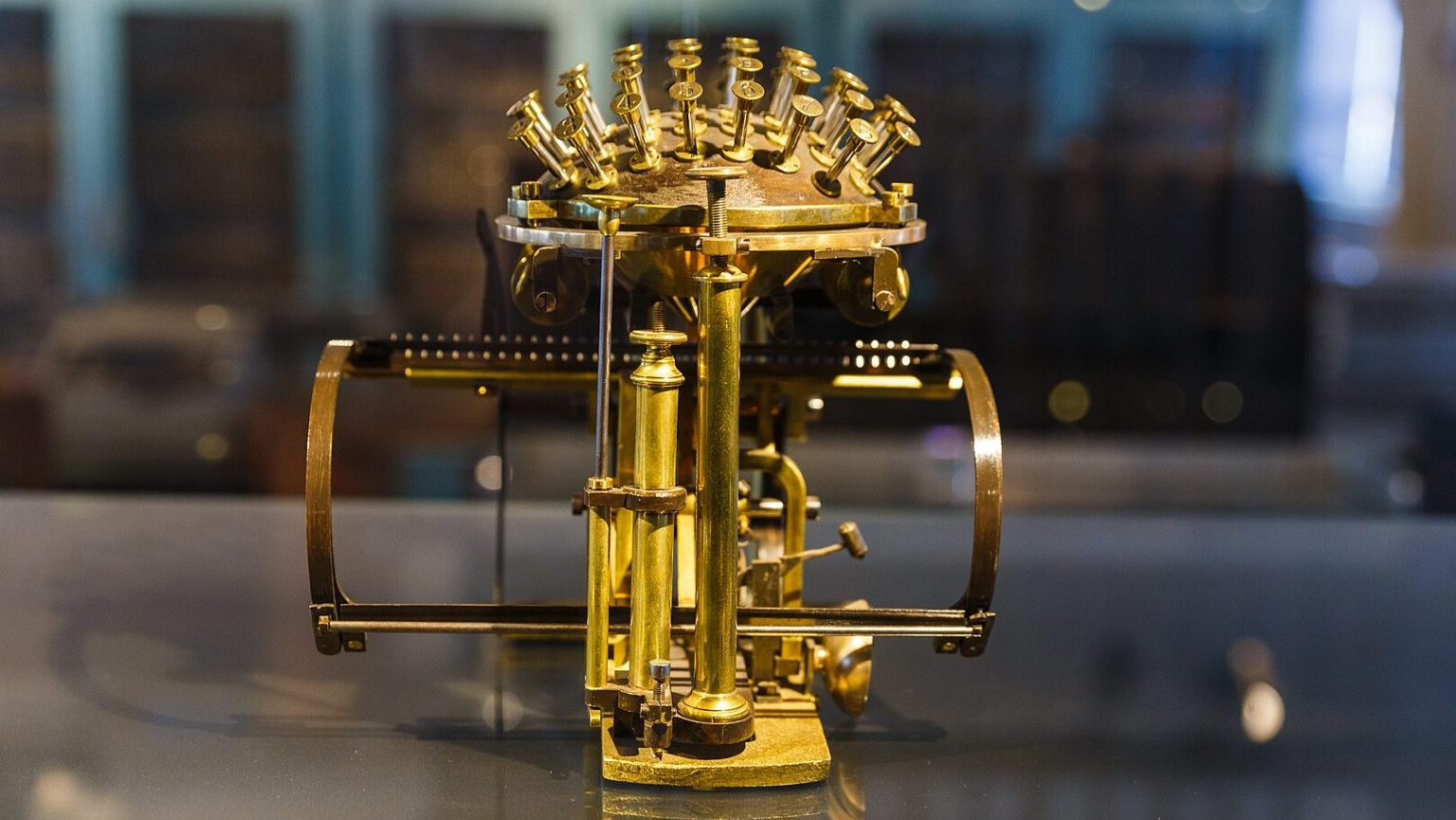

The Malling-Hansen writing ball, with its potential and limitations, redefined Nietzsche’s philosophical and creative expression.

You’re a moody person. You have to be — because understanding moods philosophically can be crucial to your work-life.

When appraising human behavior, people tend to forgo the lessons of psychology in favor of assumption and anecdote.

How black and white is your thinking?

The psychology of people who cut off all communication—and how that affects their partners.

When it comes to behavior, genetics may play a larger role than you think.

Welcome to The Nightcrawler — a weekly newsletter from Eric Markowitz covering tech, innovation, and long-term thinking.

This supremely simple hack can help you establish good habits, break bad ones, and guard against failure.

If you’re an atheist with a vocation, who laid that path for you?

Listen, set boundaries, and point them where to go.

Psychotherapist Israa Nasir explains how a “value-aligned life” can help us crush our goals — without being crushed by the need to accomplish more.

If you have any sort of power for any reasonable length of time, you will be changed by it — awareness of the effects is crucial.

“I have a friend who thinks vaccines cause autism,” writes Nina. “What can I do?”

The truly talented are those who got to where they are despite preconceived expectations.

There’s little more infuriating in the world than being told to “calm down” when you’re in the midst of a simmering grump.

How can “you” move on when the old “you” is gone?

Do you always act professionally in the workplace? Depends what you mean by “professional.”

In his latest book, Malcolm Gladwell explores a strange phenomenon of group dynamics.

Reading this article would be such a millennial thing to do.

From tribal hunts to Stonehenge and into the modern day, the peer instinct helps humans coordinate their efforts and learning.

“I am free. It’s a lot of effort to be free from the prison that is in your mind, and the key is in your pocket.” – Edith Eva Eger

Don’t make the mistake of blindly following quantitative metrics — whether you’re helping clients or looking for lunch.