grammar

Don’t worry about grammar rules at first. They’ll only trip you up.

▸

3 min

—

with

Now is the perfect time to take up a new language. Self-motivation and commitment are key to mastering this fun and useful new skill.

▸

10 min

—

with

Ever wanted to describe precisely how crummy you feel after a bad haircut?

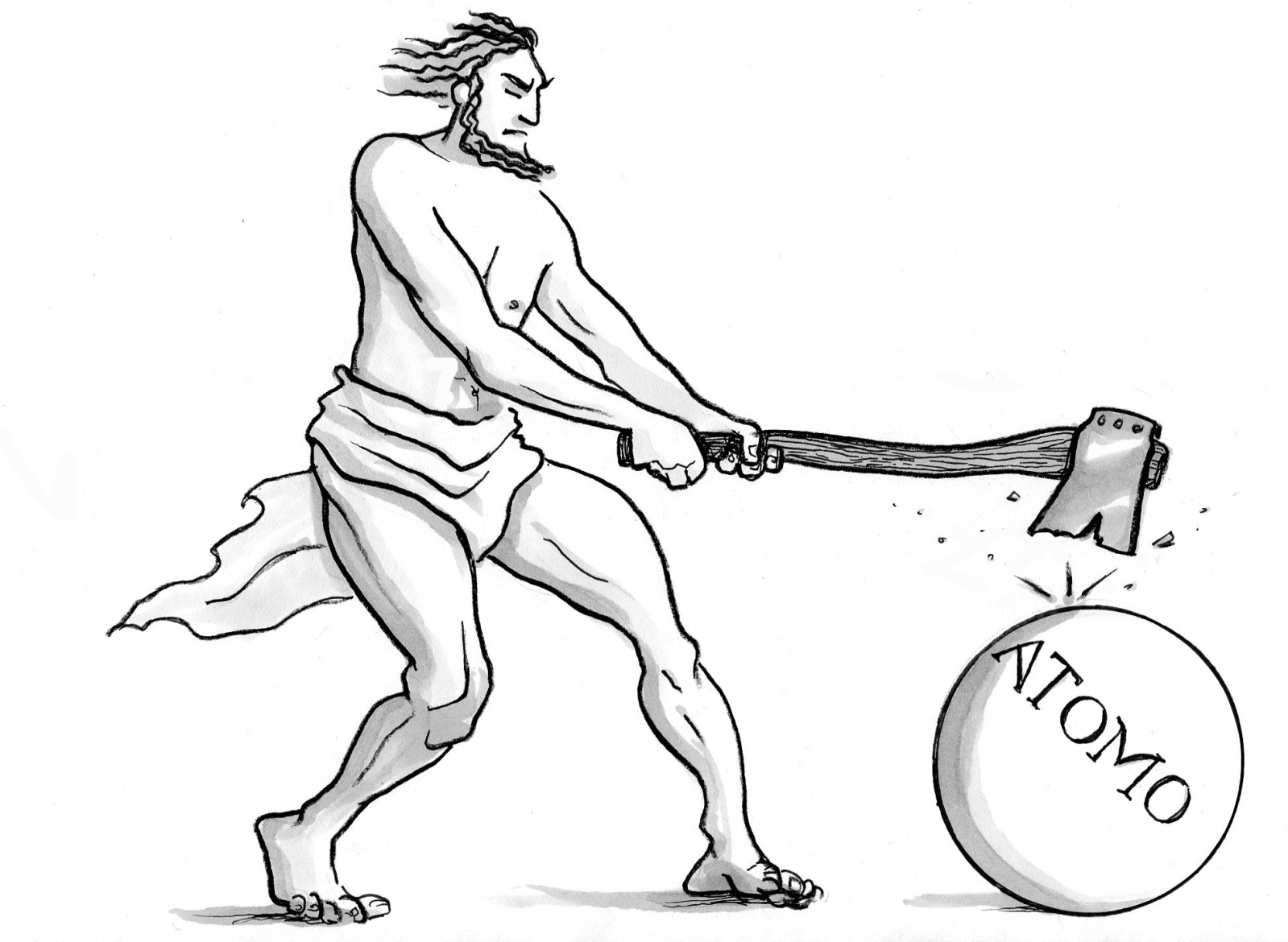

Loop quantum gravity gets the ancient atomist back into the loop, showing how black holes might explode, and that the Big Bang might be a Big Bounce.

Why do Shakespeare’s plays have such a dramatic impact on readers and audiences? Philip Davis shows how Shakespeare’s use of language creates heightened brain activity, or what he calls “a theater of the brain.”