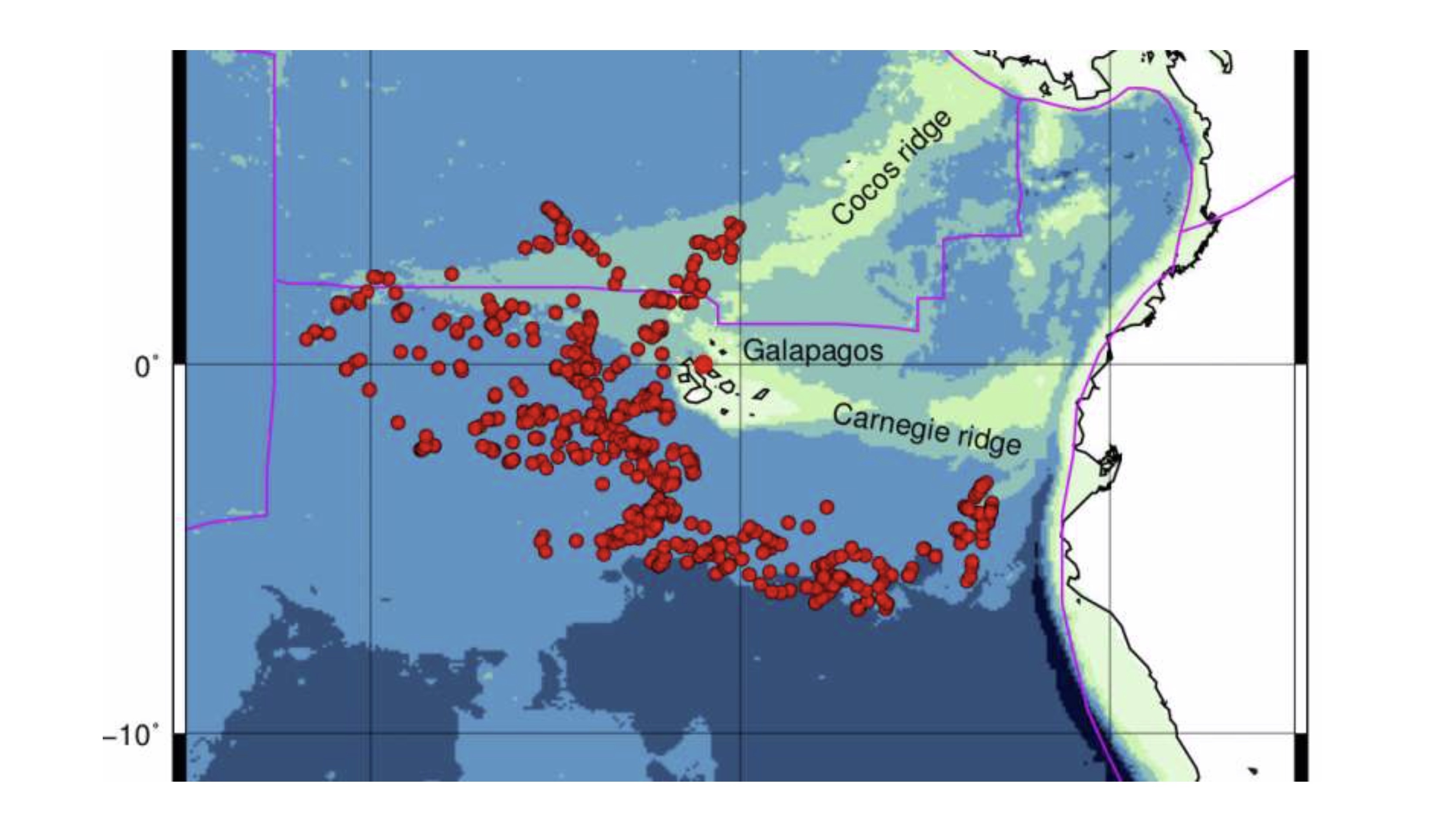

earthquakes

A network of devices called MERMAIDs is taking seismographs where they’ve never been.

The clash of tectonic plates beneath us is just part of life on Earth—unless, of course, there is human interference like in the American Midwest.

▸

4 min

—

with