distraction

Here’s why you should try to fit less—not more—into each day.

Do you get antsy when there’s nothing to do?

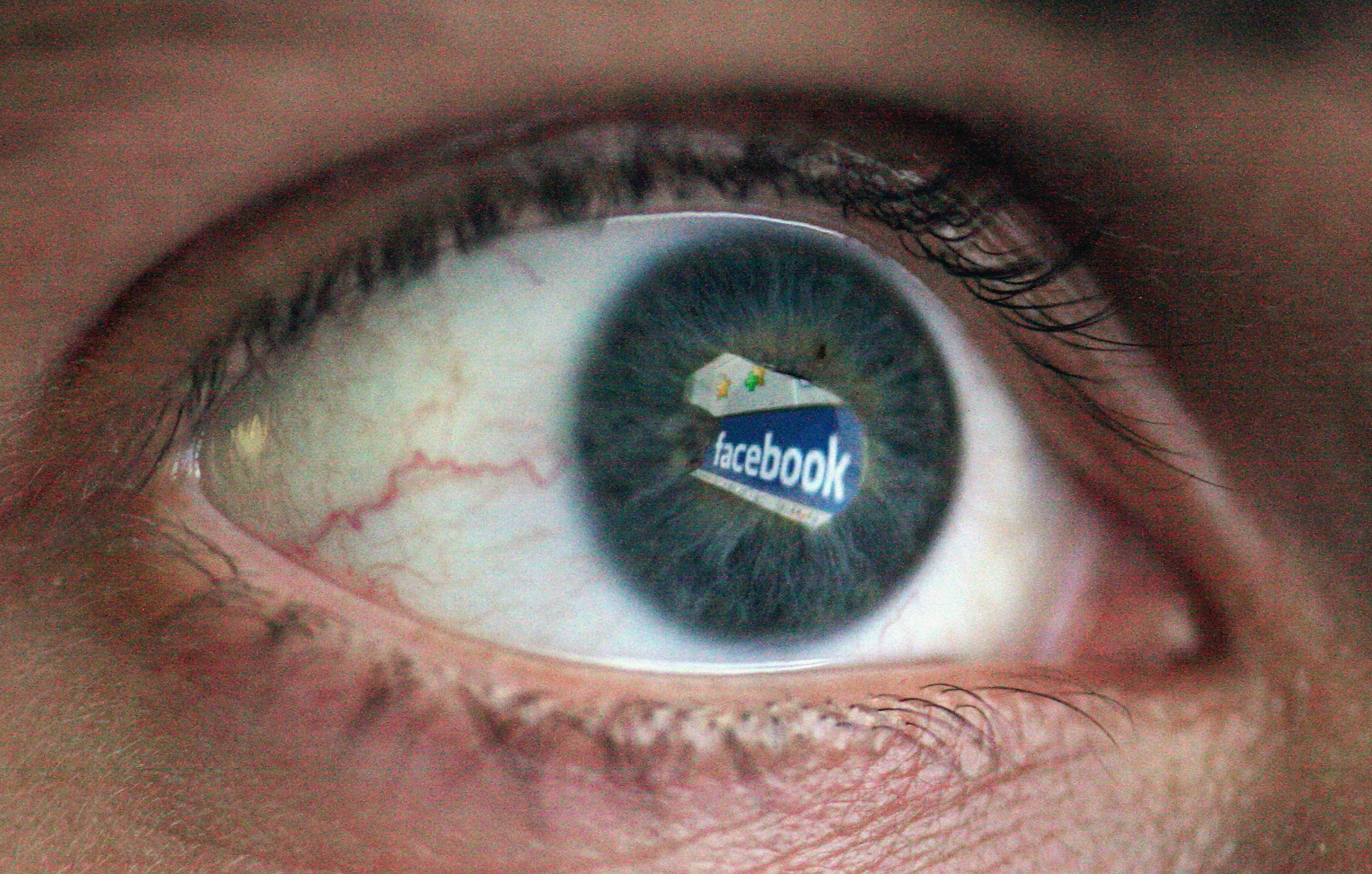

One in five employees are distracted at work by social media, a Pew Research Center poll finds.

Cross ‘multi-tasking ninja’ off your resume, it’s out, say Stanford researchers and other cognitive experts. Here are three tips for transitioning back to single-tasking.