ayahuasca

The Brazilian government has been trying to answer this very question in its ever-growing prison population, which has doubled since the year 2000.

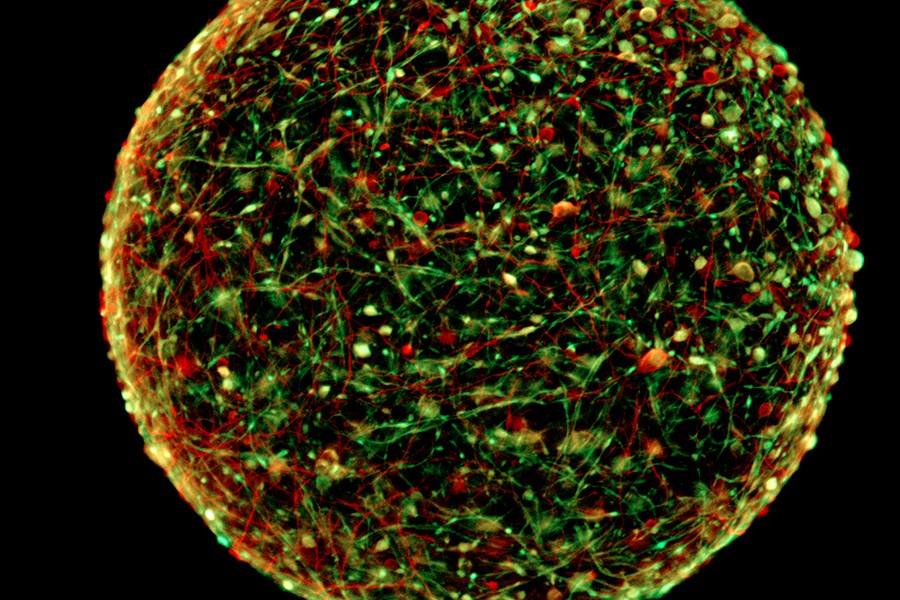

It’s the 1st observed psychedelic-caused molecular changes inside human neural tissue.

As medicine’s interest in psychedelic drugs increases,will a shamanistic brew join your therapist’s list of go to prescriptions?