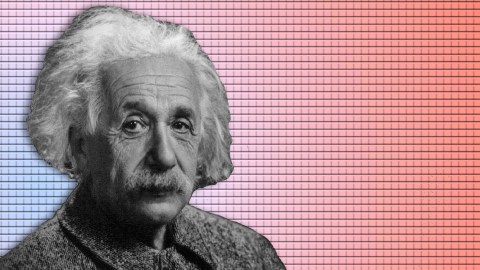

Study: People who embody Albert Einstein in VR perform better on cognitive tasks

A strange phenomenon often occurs in immersive virtual reality: people start behaving differently after taking on a virtual body—one that mirrors their real-life movements but differs in other characteristics—as if it were their own.

“Virtual reality can create the illusion of a virtual body to substitute your own, which is called virtual embodiment,” Professor Mel Slater of the University of Barcelona, author of a new study on virtual embodiment, told Science Daily. “In an immersive virtual environment, participants can see this new body reflected in a mirror and it exactly matches their movements, helping to create a powerful illusion that the virtual body is their own.”

In a new study published in Frontiers, Slater and his colleagues examined how virtual embodiment might affect cognition. The premise was simple.

“If we gave someone a recognizable body that represents supreme intelligence, such as that of Albert Einstein, would they perform better on a cognitive task than people given a normal body?” Slater said.

(Credit: Slater et al.)

To find out, the researchers asked 30 young men to participate in a virtual embodiment experiment, before which they all completed several tests that measured their planning and problem-solving skills, implicit bias toward older people, and self-esteem.

In the experiment, half of the participants took on a virtual body that resembled Albert Einstein, while the other half embodied one that looked similar to their own. The participants then retook the cognitive and implicit bias tests.

The results showed that people with low self-esteem who embodied the avatar of Albert Einstein performed significantly better on the cognitive test, and also expressed reduced bias toward older people.

“The main focus here is that embodiment does not only lead to perceptual, attitudinal and behavioral correlates as previously shown, but can also cause changes in cognitive processing,” the authors wrote.

They provided examples of past research that illustrates the “surprising plasticity of the brain’s body representation.” For example, there’s the rubber hand illusion, in which a fake hand is placed by a person’s real hand in an “anatomically plausible position” where it’s then tapped or threatened, eliciting physiological responses from people acting as if the rubber hand is their own.

In experiments on virtual embodiment and race, white participants displayed less implicit bias after taking on black virtual bodies. What’s more, a similar study showed “when White participants are embodied in a White or Black body, and interact with a Black or White virtual human, the skin color of their virtual body, rather than their real body, influenced which virtual partner they mimicked more.”

The new study expands this body of research, “demonstrating that the body type carries meaning, and that this meaning has implications for the perceptual processing, attitudes and behaviors of the person experiencing it.”

This kind of virtual embodiment technology might one day be used in schools, Slater said.

“It is possible that this technique might help people with low self-esteem to perform better in cognitive tasks and it could be useful in education.”