New ‘microneedle patch’ could help heart attack patients regrow tissue

Red human heart against a yellow background (Getty Images)

- Heart attacks leave scar tissue on the heart, which can reduce the organ’s ability to pump blood throughout the body.

- The microneedle patch aims to deliver therapeutic cells directly to the damaged tissue.

- It hasn’t been tested on humans yet, but the method has shown promising signs in research on animals.

A new ‘microneedle patch’ could someday help people regain healthy heart muscle tissue after suffering a heart attack.

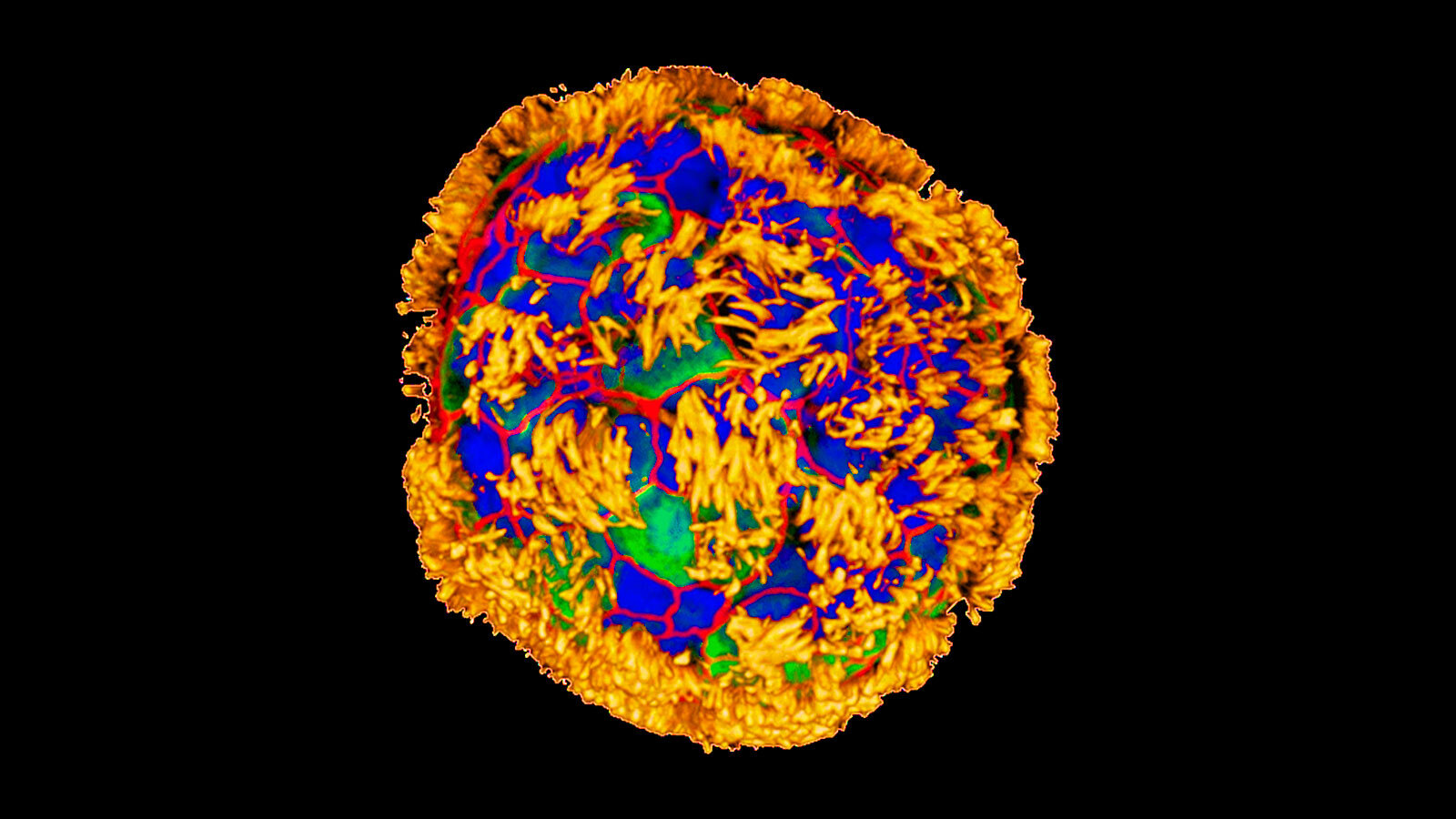

Scientists aim to surgically implant a patch made of plastic and microscopic needles directly onto the heart where it will deliver therapeutic cells to help the organ regenerate healthy tissue. The microneedles establish channels of communication between the therapeutic cells and the heart tissue, and early research on animals suggests the technique is more effective at delivering regenerative cells to the heart than others methods currently known to scientists.

It’s a bold idea that, if successful, could extend the lifespans and well-being of heart attack survivors.

A heart attack damages the muscle tissue of the heart. The injury usually heals within a few weeks, but the healing process replaces once-healthy muscle tissue with scar tissue, which isn’t as effective at pumping blood and oxygen to the heart and throughout the body. This reduced efficacy can cause heart failure, a life-threatening condition where the heart isn’t able to supply the body’s cells with enough blood.

To improve cardiac health, scientists have been searching for ways to perform cell-based heart regeneration, which involves delivering cardiac stromal cells to the heart in order to repair damaged tissue. In a research paper from November, the scientists behind the microneedle patch write that the common techniques used to deliver stromal cells to the heart aren’t very effective; cells either get washed away or delivered too slowly.

The new, more direct method could solve those problems. Preliminary research has shown it to be effective in promoting tissue regeneration in rats and pigs, but it’s still too early to tell whether it will be effective in humans. It’s also unclear how such a device might affect the heart’s regular activities.

In the U.S., more than 735,000 people suffer from heart attacks every year. A 2016 study found that nearly 25 percent of heart attack survivors went on to develop heart failure within four years of the attack.