Scientists discover first ‘intermediate-mass’ black hole in massive merger

Credit: Pixabay

- In 2019, scientists detected gravitational waves that were later determined to come from the merging of two so-called “intermediate-mass” black holes.

- These black holes were thought to exist, but had never been directly observed.

- The discovery sheds new light on how black holes form.

In May 2019, a ripple of gravitational waves passed through Earth after traveling across the cosmos for 7 billion years. The ripple came in four waves, each lasting just a fraction of a second. Although the ancient signal was faint, its source was cataclysmic: the biggest merger of two black holes ever observed.

It occurred when two mid-sized black holes — 66 and 85 times the mass of our Sun — drifted close together, began spinning around each other and merged into one black hole roughly 142 times the mass of our Sun.

“It’s the biggest bang since the Big Bang observed by humanity,” Caltech physicist Alan Weinstein, who was part of the discovery team, told The Associated Press.

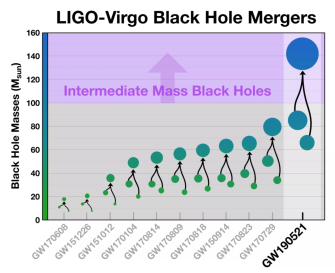

A massive bang, sure. But a black hole of this size actually falls within the “intermediate-mass” category, which ranges from about 50 to 1,000 times the mass of our Sun.

Scientists know relatively little about these mid-sized black holes. They’ve catalogued small black holes only a few times more massive than the Sun, as well as supermassive black holes more than six billion times the mass of our star. But direct evidence of intermediate-mass black holes has remained elusive.

“Long have we searched for an intermediate-mass black hole to bridge the gap between stellar-mass and supermassive black holes,” Christopher Berry, a professor at Northwestern University’s Center for Interdisciplinary Exploration and Research in Astrophysics), told Northwestern Now. “Now, we have proof that intermediate-mass black holes do exist.”

Still, how these middleweight black holes form is a mystery. Scientists know that smaller black holes form when stars explode in violent events called supernovas. But mid-sized black holes couldn’t form this way, according to current physics, because stars of a certain mass range undergo a death process called pair instability, where they explode and leave nothing behind, not even a black hole.

This chart compares the mass of black-hole merger events observed by LIGO-Virgo.Credit: LIGO/Caltech/MIT/R. Hurt (IPAC)

As for supermassive black holes? Scientists are pretty sure that these behemoths, which lie in the center of most galaxies, grow huge by gobbling up ancient dust, gas and other cosmic matter — including other black holes. Intermediate black holes may form in a similar way, by small-ish black holes repeatedly merging together.

In other words, an intermediate black hole might be on its way to becoming supermassive.

“We’re talking here about a hierarchy of mergers, a possible pathway to make bigger and bigger black holes,” Martin Hendry, a professor of gravitational astrophysics and cosmology at Glasgow University, told the BBC. “So, who knows? This 142-solar-mass black hole may have gone on to have merged with other very massive black holes — as part of a build-up process that goes all the way to those supermassive black holes we think are at the heart of galaxies.”

Visualization of a black hole.Credit: NASA

The recent discovery sheds light on how black holes form, but questions still remain. Scientists with the LIGO-Virgo collaboration hope to continue studying the newly discovered intermediate black hole — dubbed GW190521 — in 2021 when the facilities will be up and running again with improved instruments.

“Our ability to find a black hole a few hundred kilometers-wide from half-way across the Universe is one of the most striking realizations of this discovery,” Karan Jani, an astrophysicist with LIGO told The Malaysian Reserve.

The discovery was described in two papers published in the Physical Review Letters and The Astrophysical Journal Letters.