How the Big Rip could end the world

Pixabay

- A cosmological model predicts that the expanding Universe could rip itself apart.

- Too much dark energy could overwhelm the forces holding matter together.

- The disaster could happen in about 22 billion years.

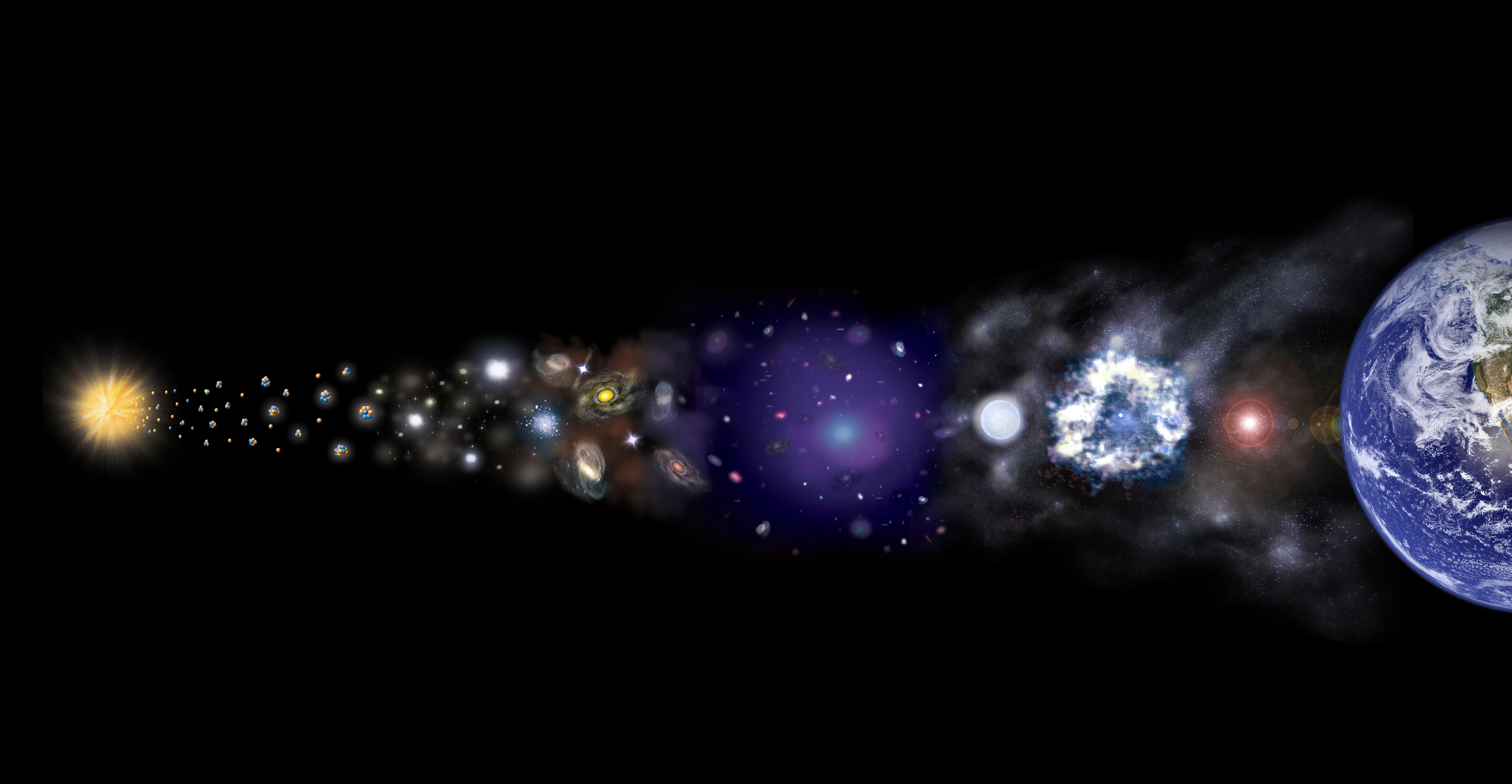

Perhaps it’s not the most cheerful thought, but people have preoccupied themselves with how the world around them could end for millennia. Now in the scientific age, one such dire prediction comes from math and physics. The theory of the Big Rip says that at some point in the distant future, the universe could rip itself apart, with everything in existence from animals to atoms becoming shredded.

”In some ways it sounds more like science fiction than fact,” said physicist Dr. Robert Caldwell of Dartmouth, who first proposed this dramatic idea in a 2003 paper he wrote with Dr. Marc Kamionkowski and Dr. Nevin Weinberg from the California Institute of Technology.

The cosmological model of the Big Rip is predicated on the notion that if the universe continues to accelerate in its expansion, it will eventually reach the point where all the forces that hold it together would be overcome by dark energy. Dark energy is the rather mysterious force that is predicted to make up 68% of the energy of the observable universe. If it overwhelms gravitational, electromagnetic and weak nuclear forces, the universe would literally come apart.

A new model of the Big Rip theory published in 2015 actually came up with the date when the Universe would meet its demise – about 22 billion years from now. The 2015 model was developed by professor Marcelo Disconzi of Vanderbilt University in collaboration with physics professors Thomas Kephart and Robert Scherrer.

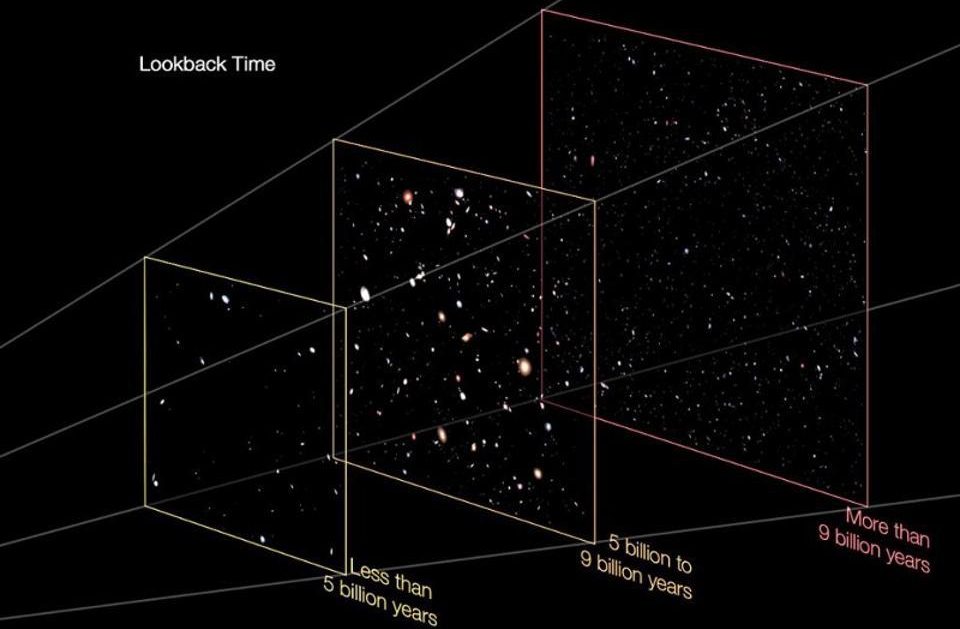

The timeline of how life universe ends up in a Big Rip.

Credit: Jeremy Teaford, Vanderbilt University

Disconzi’s hypothesis says that a Big Rip can occur when dark energy will become stronger than gravity, reaching a point when it can rip apart single atoms. The professor’s model shows that as its expansion becomes infinite, the viscosity of the universe will be responsible for its destruction. Cosmological viscosity measures how sticky or resistant the universe is to expanding or contracting.

If the Big Rip theory is correct, one day we could reach a moment when planets and everything on them will be torn apart. Then the atomic and molecular forces will be ripped open, electrons splitting from atoms, all the way down to the quarks and anything smaller. But until then, check out his video for more on the Big Rip: