There is no dark matter. Instead, information has mass, physicist says

Photo: Shutterstock

- Researchers have been trying for over 60 years to detect dark matter.

- There are many theories about it, but none are supported by evidence.

- The mass-energy-information equivalence principle combines several theories to offer an alternative to dark matter.

The “discovery” of dark matter

We can tell how much matter is in the universe by the motions of the stars. In the1920s, physicists attempting to do so discovered a discrepancy and concluded that there must be more matter in the universe than is detectable. How can this be?

In 1933, Swiss astronomer Fritz Zwicky, while observing the motion of galaxies in the Coma Cluster, began wondering what kept them together. There wasn’t enough mass to keep the galaxies from flying apart. Zwicky proposed that some kind of dark matter provided cohesion. But since he had no evidence, his theory was quickly dismissed.

Then, in 1968, astronomer Vera Rubin made a similar discovery. She was studying the Andromeda Galaxy at Kitt Peak Observatory in the mountains of southern Arizona when she came across something that puzzled her. Rubin was examining Andromeda’s rotation curve, or the speed at which the stars around the center rotate, and realized that the stars on the outer edges moved at the exact same rate as those at the interior, violating Newton’s laws of motion. This meant there was more matter in the galaxy than was detectable. Her punch card readouts are today considered the first evidence of the existence of dark matter.

Many other galaxies were studied throughout the ’70s. In each case, the same phenomenon was observed. Today, dark matter is thought to comprise up to 27% of the universe. “Normal” or baryonic matter makes up just 5%. That’s the stuff we can detect. Dark energy, which we can’t detect either, makes up 68%.

Dark energy is what accounts for the Hubble Constant, or the rate at which the universe is expanding. Dark matter on the other hand, affects how “normal” matter clumps together. It stabilizes galaxy clusters. It also affects the shape of galaxies, their rotation curves, and how stars move within them. Dark matter even affects how galaxies influence one another.

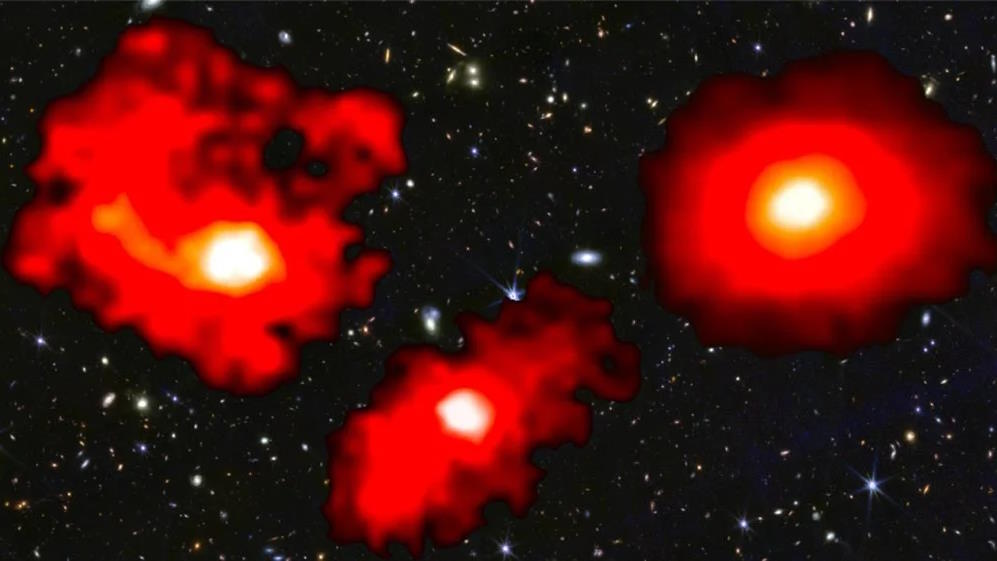

NASA writes: ‘This graphic represents a slice of the spider-web-like structure of the universe, called the “cosmic web.” These great filaments are made largely of dark matter located in the space between galaxies.’

Credit: NASA, ESA, and E. Hallman (University of Colorado, Boulder)

Leading theories on dark matter

Since the ’70s, astronomers and physicists have been unable to identify any evidence of dark matter. One theory is it’s all tied up in space-bound objects called MACHOs (Massive Compact Halo Objects). These include black holes, supermassive black holes, brown dwarfs, and neutron stars.

Another theory is that dark matter is made up of a type of non-baryonic matter, called WIMPS (Weakly Interacting Massive Particles). Baryonic matter is the kind made up of baryons, such as protons and neutrons and everything composed of them, which is anything with an atomic nucleus. Electrons, neutrinos, muons, and tau particles aren’t baryons, however, but a class of particles called leptons. Even though the (hypothetical) WIMPS would have ten to a hundred times the mass of a proton, their interactions with normal matter would be weak, making them hard to detect.

Then there are those aforementioned neutrinos. Did you know that giant streams of them pass from the Sun through the Earth each day, without us ever noticing? They’re the focus of another theory that says that neutral neutrinos, that only interact with normal matter through gravity, are what dark matter is comprised of. Other candidates include two theoretical particles, the neutral axion and the uncharged photino.

Now, one theoretical physicist posits an even more radical notion. What if dark matter didn’t exist at all? Dr. Melvin Vopson of the University of Portsmouth, in the UK, has a hypothesis he calls the mass-energy-information equivalence. It states that information is the fundamental building block of the universe, and it has mass. This accounts for the missing mass within galaxies, thus eliminating the hypothesis of dark matter entirely.

Information theory

To be clear, the idea that information is an essential building block of the universe isn’t new. Classical Information Theory was first posited by Claude Elwood Shannon, the “father of the digital age” in the mid-20th century. The mathematician and engineer, well-known in scientific circles—but not so much outside of them, had a stroke of genius back in 1940. He realized that Boolean algebra coincided perfectly with telephone switching circuits. Soon, he proved that mathematics could be employed to design electrical systems.

Shannon was hired at Bell Labs to figure out how to transfer information over a system of wires. He wrote the bible on using mathematics to set up communication systems, thereby laying the foundation for the digital age. Shannon was also the first to define one unit of information as a bit.

There was perhaps no greater proponent of information theory than another unsung paragon of science, John Archibald Wheeler. Wheeler was part of the Manhattan Project, worked out the “S-Matrix” with Niels Bohr and helped Einstein develop a unified theory of physics. In his later years, he proclaimed, “Everything is information.” Then he went about exploring connections between quantum mechanics and information theory.

He also coined the phrase “it from bit” or that every particle in the universe emanates from the information locked inside it. At the Santa Fe Institute in 1989, Wheeler announced that everything, from particles to forces to the fabric of spacetime itself “… derives its function, its meaning, its very existence entirely … from the apparatus-elicited answers to yes-or-no questions, binary choices, bits.”

Part Einstein, part Landauer

Vopson takes this notion one step further. He says that not only is information the essential unit of the universe but also that it is energy and has mass. To support this claim, he unifies and coordinates special relativity with the Landauer Principle. The latter is named after Rolf Landauer. In 1961, he predicted that erasing even one bit of information would release a tiny amount of heat, a figure which he calculated. Landauer said this proves information is more than just a mathematical quantity. This connects information to energy. Through experimental testing over the years, the Landauer Principle has held up.

Vopson says, “He [Landauer] first identified the link between thermodynamics and information by postulating that logical irreversibility of a computational process implies physical irreversibility.” This indicates that information is physical, Vopson says, and demonstrates the link between information theory and thermodynamics.

In Vopson’s theory, information, once created has “finite and quantifiable mass.” It so far applies only to digital systems, but could very well apply to analogue and biological ones too, and even quantum or relativistic-moving systems. “Relativity and quantum mechanics are possible future directions of the mass-energy-information equivalence principle,” he says.

In the paper published in the journal AIP Advances, Vopson outlines the mathematical basis for his hypothesis. “I am the first to propose the mechanism and the physics by which information acquires mass,” he said, “as well as to formulate this powerful principle and to propose a possible experiment to test it.”

The fifth state of matter

To measure the mass of digital information, you start with an empty data storage device. Next, you measure its total mass with a highly sensitive measuring apparatus. Then, you fill it and determine its mass. Next, you erase one file and evaluate it again. The trouble is, the “ultra-accurate mass measurement” device the paper describes doesn’t exist yet. This would be an interferometer, something similar to LIGO. Or perhaps an ultrasensitive weighing machine akin to a Kibble balance.

“Currently, I am in the process of applying for a small grant, with the main objective of designing such an experiment, followed by calculations to check if detection of these small mass changes is even possible,” Vopson says. “Assuming the grant is successful and the estimates are positive, then a larger international consortium could be formed to undertake the construction of the instrument.” He added, “This is not a workbench laboratory experiment, and it would most likely be a large and costly facility.” If eventually proved correct, Vopson will have discovered the fifth form of matter.

So, what’s the connection to dark matter? Vopson says, “M.P. Gough published an article in 2008 in which he worked out … the number of bits of information that the visible universe would contain to make up all the missing dark matter. It appears that my estimates of information bit content of the universe are very close to his estimates.”