Will antidepressant medications ever require informed consent?

Image by Elisa Riva

- The directors of the new documentary, “Medicating Normal,” want psychiatrists to require informed consent when writing prescriptions.

- Long-term effects of antidepressant usage do not have to be documented for FDA approval.

- Big Think talks to producer/director Wendy Ratcliffe and film subject, Angela Peacock.

While humoral theory was finally abandoned with the acceptance of germ theory, Hippocrates offered many important insights into the nature of disease. The humors pointed to bodily causes of disease at a time when many thought divine forces were at play. (“Men think [epilepsy] divine merely because they do not understand it,” wrote one Hippocratic student.) Though disease specificity of blood and phlegm took time to understand, important ramifications for the future of medicine were being considered nearly 2,500 years ago.

The most interesting humor was black bile. Black liquid secreted by the spleen, the temperamental correlation resonates: melancholy. Hippocratic students recognized depression as an imbalance and sought methods to cure it. Over the centuries, various tinctures and herbs addressed melancholy. Doctors agreed targeted medicine helped the patient overcome the imbalance leading to depression; they also believed depression was a natural state that everyone experiences from time to time.

Our views on depression changed when twentieth-century pharmacology entered the picture. Doctors had terrible ideas, such as electroshock therapy and lobotomies, but one of the worst might be the chemical imbalance theory of the brain. As former psychiatrist Dean Schuyler wrote in his 1974 book, most depressive episodes “will run their course and terminate with virtually complete recovery without specific intervention.”

That’s not how the growing pharmaceutical industry treated it. The pathologizing of depression meant that doctors—in this case, psychiatrists—could diagnose and treat what had long been considered a natural part of life. As often happens in drug development, a substance is discovered and only then is a disease needed for it to treat. Mental health seems particularly useful in this process.

Depression wasn’t the only mental health condition to be pathologized. Anxiety is a big one. Lack of focus is another. Any minor deviation from a perceived norm has, over the course of the 20th century, become subjected to diagnosis and, thanks to the lobbying power of the pharmaceutical industry, pharmacological treatments with little to no informed consent.

Take Angela Peacock, an Iraq War veteran that was medically retired due to PTSD. Upon her return in 2004, she was put on one drug after another. By 2006, that meant 18 different drugs. “That took away my ability to even know there’s anything wrong with that,” she recently told me prior to an online screening of “Medicating Normal“ a new documentary that challenges the market for increasingly over-prescribed and under-studied prescription drugs.

EarthRise Podcast 93: Medicating Normal (with Angela Peacock & Wendy Ratcliffe)www.youtube.com

During our talk, Peacock is seated next to director and producer, Wendy Ratcliffe. Co-director Lynn Cunningham was initially inspired to pursue this topic when a family member’s health deteriorated after 15 years of psychiatric medication. A Harvard graduate and star athlete, this family member is now on disability and exhibits poor mental health.

This brings up a question modern psychiatry rarely confronts: Why are prescription drug rates and rates of anxiety and depression increasing? If the former worked, shouldn’t the latter be in decline?

That’s not what’s happened. Ratcliffe decided to produce “Medicating Normal” after reading Robert Whitaker’s 2010 book, “Anatomy of an Epidemic.” (Whitaker is featured in the film and was recently featured in my column.) For over three years, the crew followed five people (including Peacock) around as they dealt with the terrifying health consequences of medication dependence.

“These medicines are causing an epidemic of disability,” Ratcliffe says. When I ask what she learned about the pharmaceutical industry while making the film, her eyes light up. She shakes her head in disbelief.

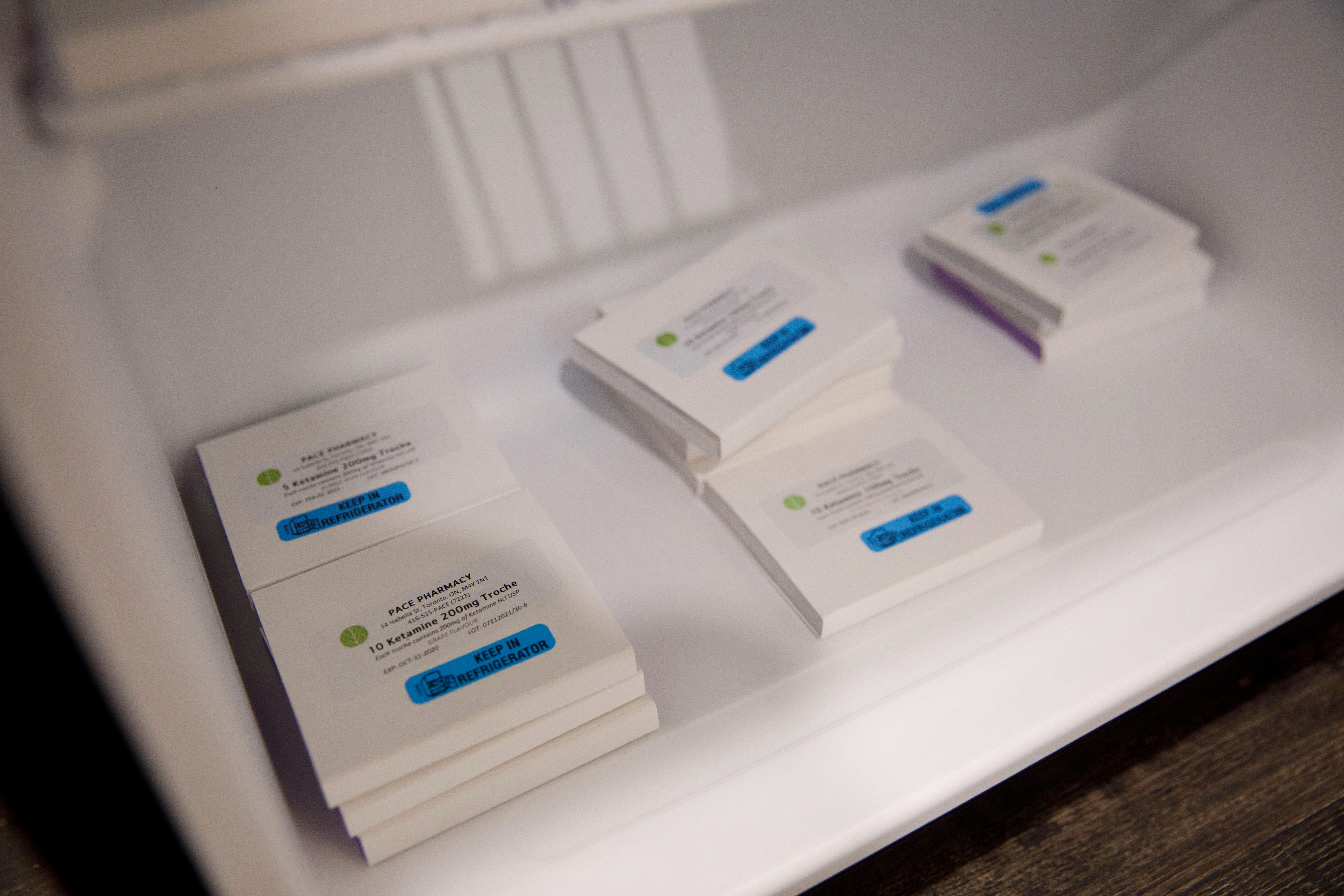

“I’m totally shocked by the FDA process: medications that are designed to be taken for many years or even a lifetime, to get them approved they only have to be shown to work better than a placebo over three to six weeks. There is no obligation to test these drugs for long-term side effects. I was shocked to discover that pharmaceutical companies pay for most of the research on their own drugs. They design the research to get the result that they want. When they don’t like the result of the trial, they throw it out.”

Whitaker told me about the original trial for the benzodiazepine, Xanax. At four weeks, it outperformed the placebo. At eight weeks, however, there was no discernible difference between the placebo and Xanax. By 14 weeks, the placebo outperformed Xanax. To get around this inconvenient data, Upjohn only reported the four-week data. The FDA approved the drug.

That was in 1980. In 2017, 25 million Xanax prescriptions were written.

Pharmaceutical companies understand how to get FDA approval. Like oil companies, they’re clueless when tragedy strikes. They don’t know how to deal with the long-term side effects of their drugs, so they ignore them. Ratcliffe says the doctors she talked with weren’t trained in tapering protocols or educated about the negative impact of the drugs they prescribe. The reflexive response is another drug, not an honest investigation of the drugs themselves.

Wendy Ratcliffe and Lynn Cunningham at the premiere of Medicating Normal at the Santa Barbara International Film Festival.Credit: Wendy Ratcliffe

This is the process that led to Peacock being prescribed 18 drugs at once. The side effects, she confirms, are not minor.

“From a patient standpoint, I thought dizziness meant I had to get up slowly. The dizziness I experienced coming off of antidepressants and benzodiazepines was like, I can’t walk. It was like walking on the Grand Canyon in high heels on a tight wire.”

Though the final benzodiazepine nearly killed her, Peacock finally abandoned all drugs in 2016. Today, she feels old parts of herself coming back, but she’s not yet whole. She’s not sure she’ll ever be. Currently living in her RV, she travels around the country educating former vets and promoting the documentary. Unlike her time on prescription drugs, she now has a mission.

“The way we bring people home from war and then put them on drugs is not right,” she says. She is doing her best to change that fact.

Both women agree on an important point: psychiatry needs informed consent. The problem, Ratcliffe says, is that “psychiatry lobbying groups feel that informed consent impedes their ability to prescribe.” She compares the industry to the NRA: any criticism is treated as a potential keystone that, if removed, will take out the entire system. In reality, all patients are asking for is honesty about how these drugs interact in their bodies.

We don’t know the long-term effects because pharmaceutical companies don’t have to study them. If the industry isn’t required to disclose these effects, and psychiatrists remain ignorant of the real damage being done to some of their patients, informed consent remains an intangible dream with no pathway to reality.

As Whitaker writes in “Anatomy of an Epidemic,” antidepressants don’t treat chemical imbalances—they create them. Over 2,500 years ago, doctors recognized melancholy as a natural part of life—one that, as Schuyler and others realized, goes away with time. Yet for a growing number of Americans, depression will never fade because they weren’t informed about the potential consequences of the prescription they were handed. They never know what they’re being told to swallow.

—

Stay in touch with Derek on Twitter, Facebook and Substack. His next book is “Hero’s Dose: The Case For Psychedelics in Ritual and Therapy.”