New air-conditioning design cools without using fossil fuels

Linda Cicero, Stanford News

- Scientists at Stanford have developed what is essentially a fossil-free air conditioner.

- It absorbs solar energy, creates a heat sink, and releases that heat through radiative cooling.

- The device is still in development.

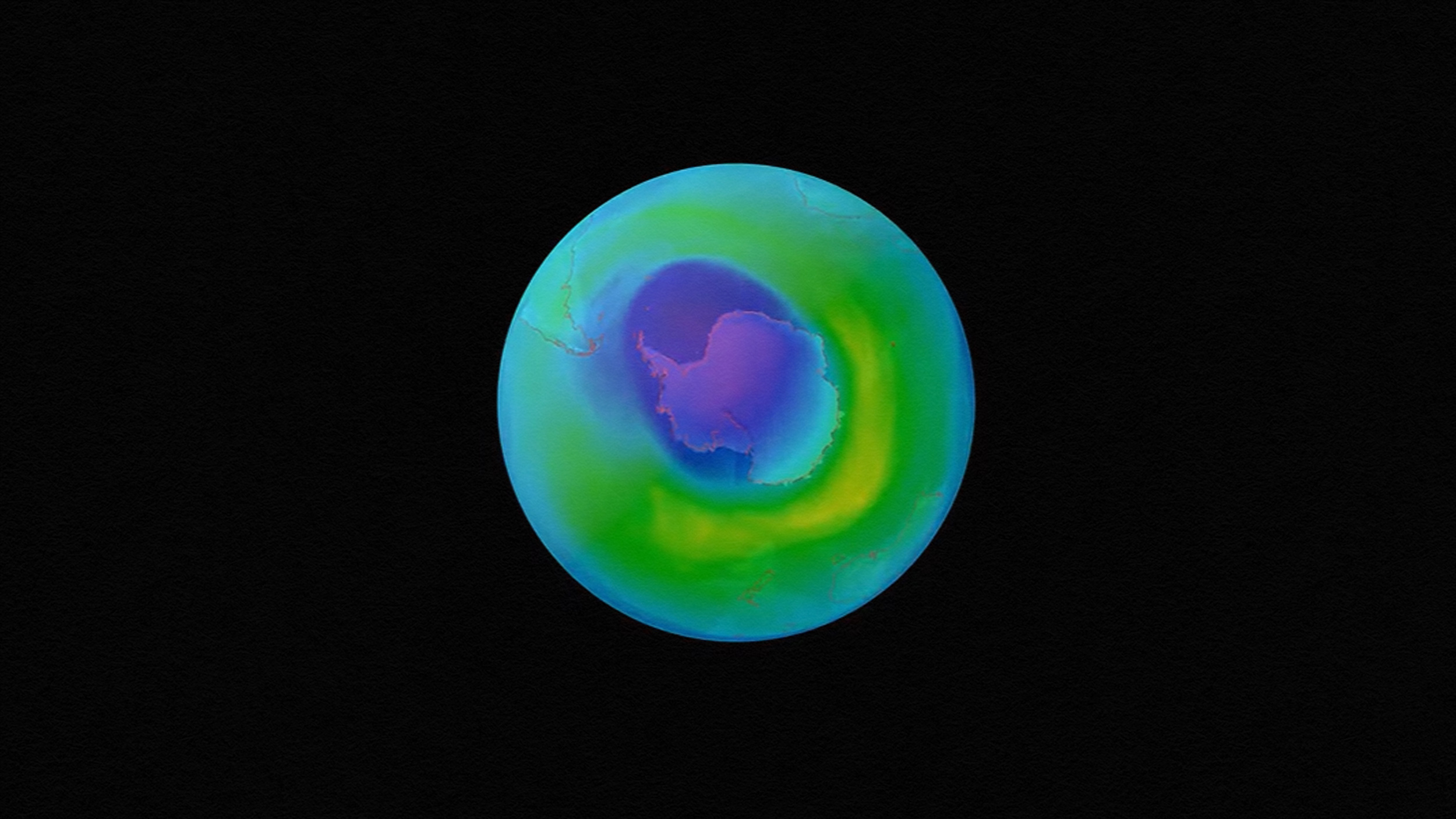

Air conditioners have historically been a ‘known known’ for their impact on the Ozone layer for decades. The damage levied in the stratosphere by chlorofluorocarbons — emitted in no small part by said air conditioners — spurred the signing of The Montreal Protocol in 1987. Because of the agreement to reduce the amount of chlorofluorocarbons put into the air, the hole that had opened up in the Ozone layer over Antarctica is expected to return to the levels seen in the 1980s by 2050.

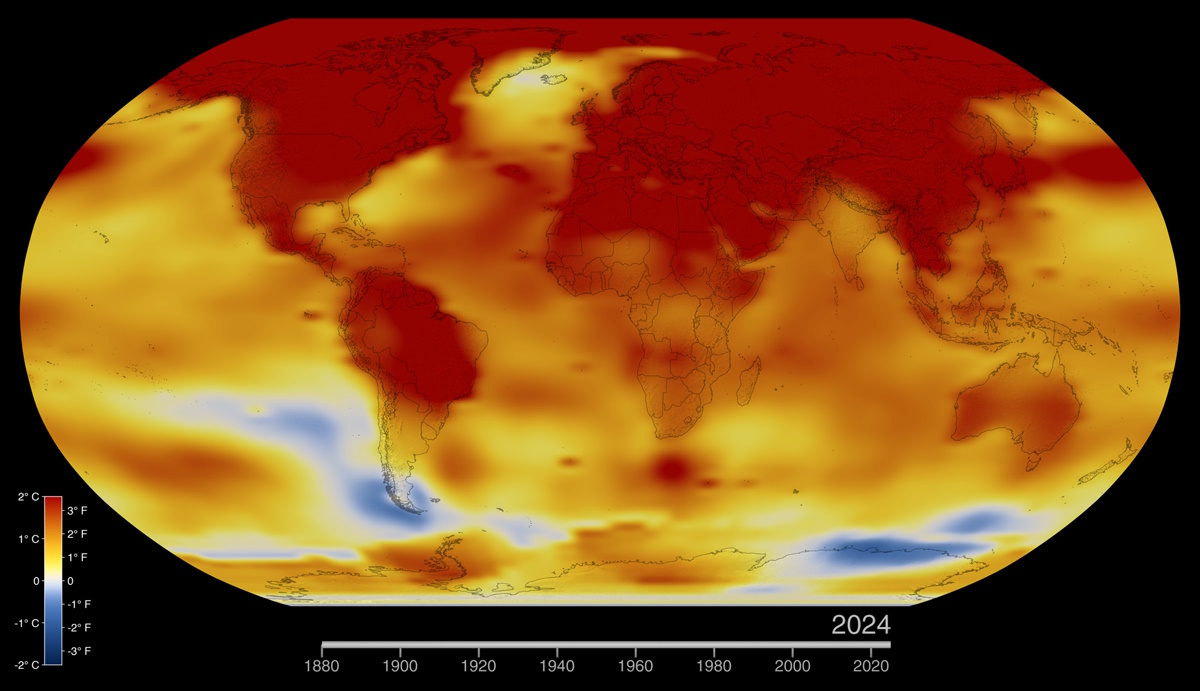

But that doesn’t mean that the problem is solved: air conditioning units still contribute to global warming. The chemicals that replaced the chlorofluorocarbons in old air conditioners are “2,100 times that of carbon dioxide” in their warming effect on the planet, as noted in The New York Timesin 2012. Two hundred countries stepped in to regulate this in 2016. Even so: air conditioning use emits 100 million tons of CO2 into the air every year.

Which is why it’s noteworthy that scientists at Stanford have developed air-conditioning free of fossil fuels.

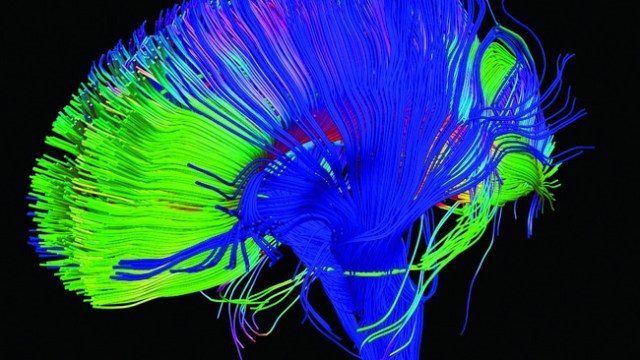

The basic idea at hand is this: the device pictured above will absorb solar energy with its top layer and then shoot that heat back into space in the form of radiation using the bottom layer. The device creates a heat sink — which is what it sounds like: something that absorbs excess heat — and then cools a targeted area through radiative cooling. Or, as one of the lead authors of the paper attached to the device put it: “We’ve built the first device that one day could make energy and save energy, in the same place and at the same time, by controlling two very different properties of light.”

Radiative cooling is when an object lets off heat in infrared light. When these devices release infrared heat, they release it at a wavelength that can pass through Earth’s atmosphere and into space.

The device remains in development and is far from ready for commercial use — the scientists here have yet to even see if they can generate electricity from the device — but, given the stakes of global warming and climate change, it is an intriguing development worthy of attention.