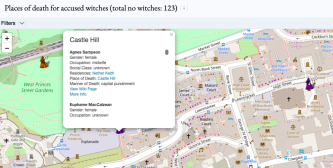

Find over 3,000 witches on this map of Scotland

Image: Accused Witches Map project, Edinburgh University.

Proof of godliness

Looking for a witch but don’t know where to find one? This map will help. It pins more than 3,000 people accused of witchcraft to a map of Scotland. It’s the Grand Register of Scottish Witchcraft that you never knew you needed.

But only if your interest is purely academic. You can’t call or write them to cast a spell on your behalf, because they’re all dead and gone. And not just because many were executed. This Map of Accused Witches geo-locates the entries in the Survey of Scottish Witchcraft database (SoSW), which covers the period between 1563 and 1736.

Those years bookend a very specific period:

- In 1563, the Scottish Parliament passed the Witchcraft Act, which made witchcraft a capital crime.

- And in 1735, another Witchcraft act, this time passed by the Parliament in Westminster, made it a crime to accuse others of having magical powers or of practicing witchcraft, throughout the whole of Britain (including Scotland).

In other words, the map covers more than 170 years of government-sanctioned witch hunting and killing in Scotland. For a state with a religious point to make, prosecuting witchcraft was an excellent way to prove its godliness.

Places of residence of accused witches in the Greater Edinburgh area.

Image: Accused Witches Map project, Edinburgh University.

Mark of the Devil

In that period, more than 3,200 people were publicly accused of being witches in Scotland. Whether motivated by religious zeal or naked opportunism, witch-hunting was pursued with remarkably more fervor in Scotland than in England.

The alleged witches in the database defy the stereotypes that later times have conferred on them. They are neither all female (15% were men), nor particularly old (half were under 40). They were also not typically widowed, nor all poor outsiders (most were ‘middle class’, some were nobility), nor generally practitioners of folk medicine (only about 4%).

A conviction could result from confessions – by the suspects or by other witches – or if the Devil’s mark was found on the body of the suspect. The Devil was believed to ‘mark’ his followers when they made their pact with him, detectable either as a visible blemish or an insensitive spot. ‘Witch-prickers’ used pins and knives to find those spots, and thus identify the suspects as actual witches. There are known to have been at least 10 professional itinerant witch-prickers in Scotland at the time.

23 witches were executed at Castle Hill in Edinburgh, four more just down the road, at Mercat Cross (to the right).

Image: Accused Witches Map project, Edinburgh University.

Torture and death

One of the most effective and most frequently used forms of torture used on accused witches was sleep deprivation; it leads to hallucinations, which is a very helpful tool for obtaining confessions. Physical torture was relatively rare.

Only for a relatively small sample – 55 cases – are methods of torture mentioned, which included: forcing the accused to wear haircloth, whipping them, binding them with ropes, hanging them by their thumbs, placing them in iron and stocks, putting them in cashielaws (a.k.a. the ‘warm hose’: iron leg encasings which were heated until the legs began to roast).

And only in 305 of the 3,212 cases in the database is the sentence known:

- 205 were executed,

- 52 acquitted,

- 27 banished,

- 11 declared fugitive,

- 6 excommunicated,

- 2 ‘put to the horn’ (i.e. outlawed),

- 1 kept in prison and

- 1 publicly humiliated.

A further 98 fled from prosecution. The first figure above seems to suggest that about two thirds were executed. For the entire group, that would mean more than 2,000 witches executed. But researchers say the sample is too small and atypical for that kind of conclusion.

John Kincaid was mainly active around Edinburgh, but ventured as far south as Newcastle, in England, and as far north as Brechin. There, in April 1650, Kincaid found the devil’s mark on the body of Catharin Walker. She had been accused of unorthodox religious practise. And it was said she had kicked a man in the groin who had subsequently died; that people suffered after she quarrelled with them; and that she had confessed to having suffocated and poisoned her own children. She did not immediately confess, but in prison admitted that she had pacted with the Devil, in the shape of a cat.

Image: Accused Witches Map project, Edinburgh University.

Journey of a witch-pricker

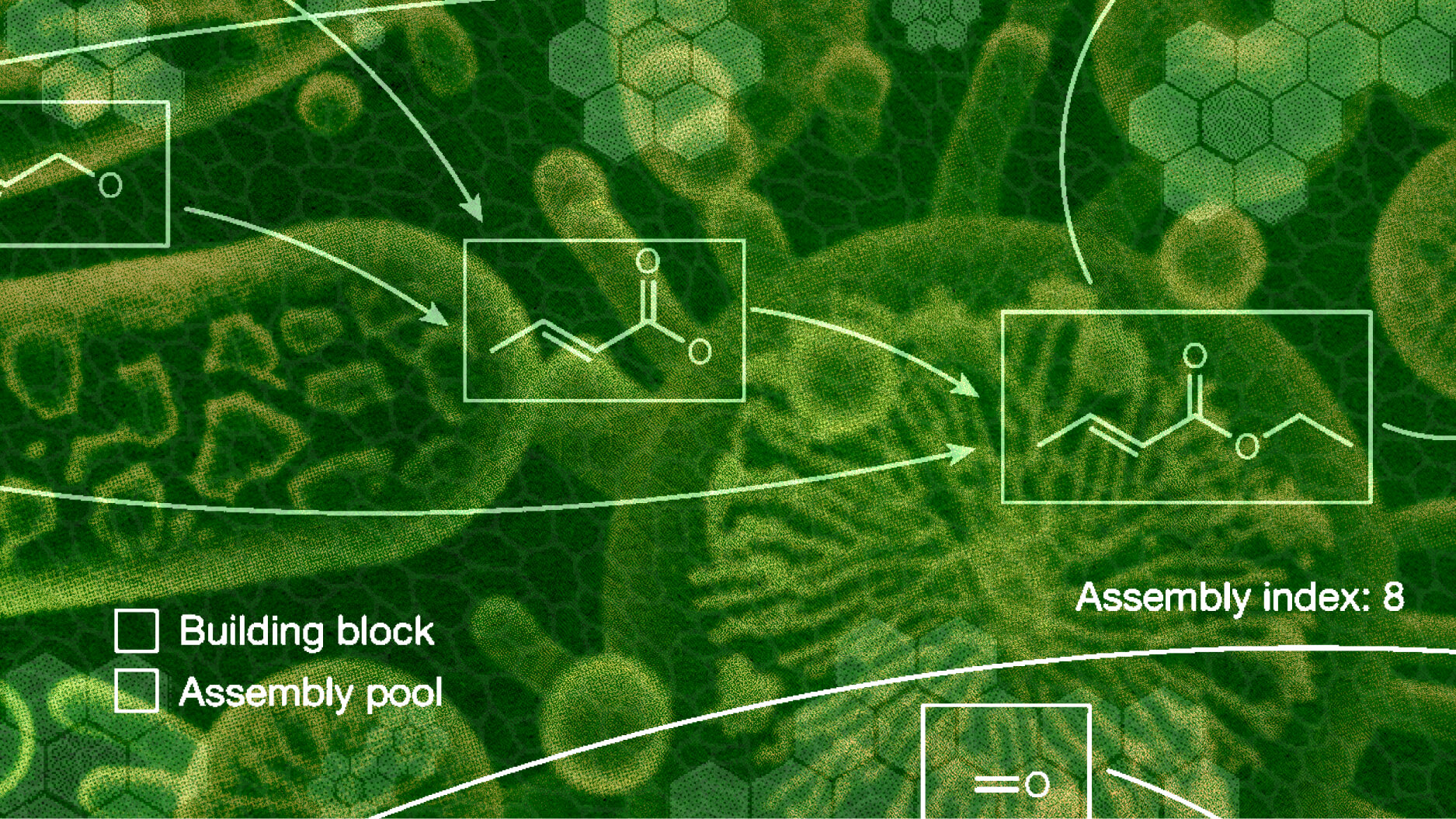

In order to unlock the data contained in the SoSW database, the University of Edinburgh in 2018-19 launched a project to locate and visualise the various places it recorded. It was the first time this dataset of alleged Scottish witches had been geo-located so exhaustively.

Mid-2019, Emma Carroll, a Geology and Physical Geography undergraduate student, was taken on board as ‘witchfinder general’: to locate the witches on the map of Scotland. “Before the internship I had barely even heard of Haddington and now I know that it is the witch capital of Scotland,” she remarked on the blog detailing her progress.

Carroll had to find locations for which the name or spelling had changed dramatically, or which had disappeared off the map altogether. Her detective work involved scouring old, detailed Ordnance Survey maps and even older maps of Scotland, contemporary to the witch trials, including the Blaeu Atlas of Scotland (1654).

Carroll’s work consisted not only of geo-locating the places of residence, detainment, trial and (if applicable) execution for the accused, but also of pinpointing locations for the more around 2,000 other people associated with the trials – ministers, sheriffs, and others.

The detective work also shed some new light on some of the cases, like that of Marie Nian Innes, of the Isle of Skye. The fact that she was accused of witchcraft may have had more to do with local politics; specifically, with the new local clan chief Ranald attempting to assert his authority.

Carroll prepared various maps based on the information at her disposal, including one ‘story map’, on John Kincaid, “a notoriously evil witch-pricker” from Tranent. Kincaid was involved in 17 cases – in one of which he was the accused.

Devil’s sermon and witches’ brew – one of the few contemporary illustrations of Scottish witchcraft.

Image: British Library – public domain

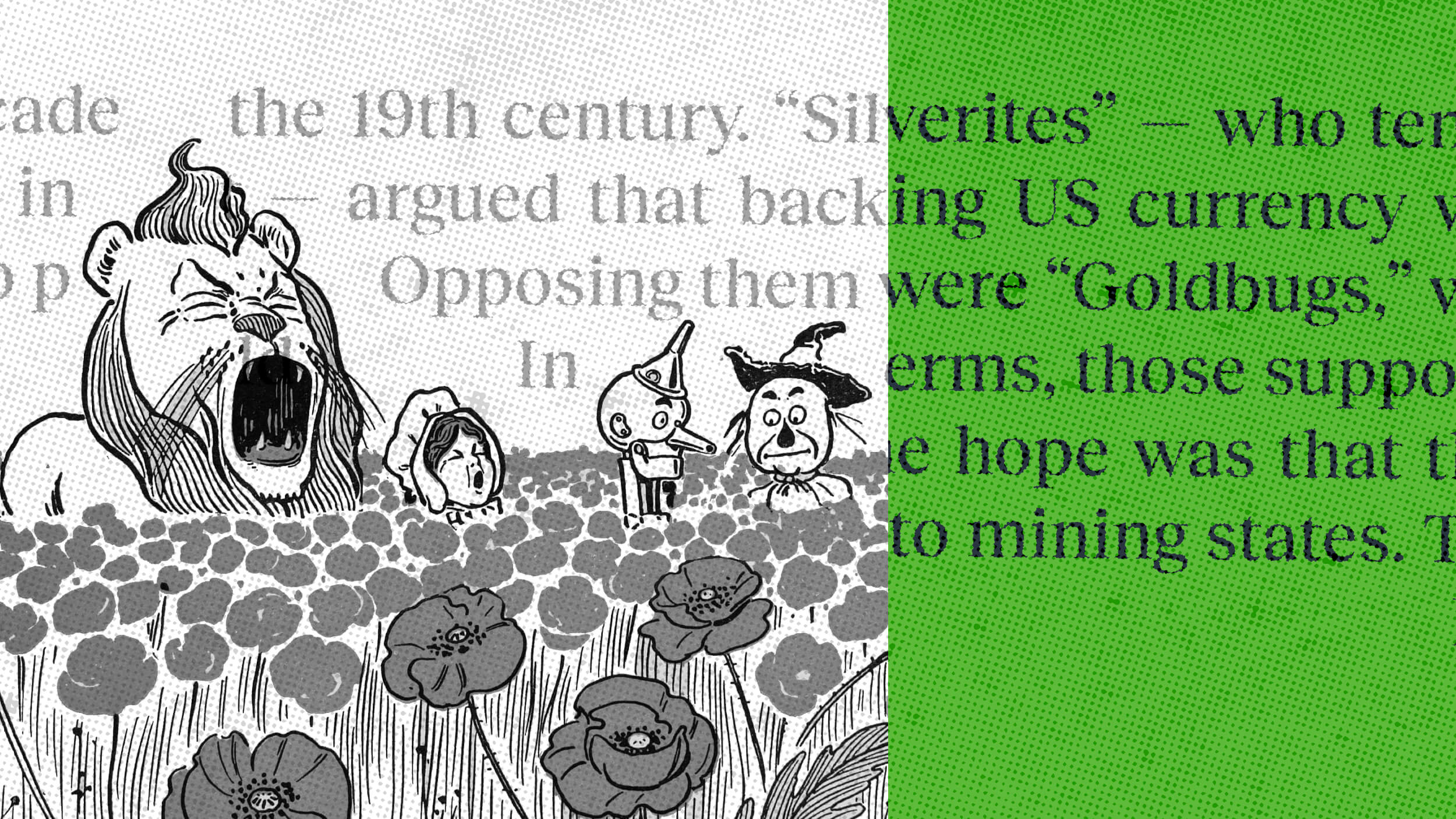

The North Berwick Witch Trials

One of the focal points of the map is North Berwick, which was the scene in 1590-91 of the infamous North Berwick Witch Trials, presided over by King James IV of Scotland himself. The trials were discussed in the anonymous pamphlet Newes from Scotland, published in London in 1591. It contains the only contemporary illustrations of Scottish witchcraft. One of them is this woodcut (above), which shows:

- A group of witches (center) listening to a sermon by the Devil (left) at North Berwick church on Halloween of the year 1590. Haddington schoolmaster John Fian (in between) is acting as the witches’ clerk.

- A ship sunk by witchcraft (top left). Local witches were accused of raising the storm that had troubled the North Sea voyage of Anne of Denmark, bride of King James (later also King James I of England). Although none of the ships in that party was sunk, witches were accused of sinking a ferry in the Forth, and a ship named Grace of God at North Berwick itself.

- Witches stirring a cauldron. Boilerplate witchery, not directly related to any accusations in the witch hunts of 1590-91.

- A pedlar (right) discovers witches in Tranent, and is then magically transported to a wine-cellar in Bordeaux, France (bottom right).

Newes from Scotland was probably written by James Carmichael, the minister of Haddington. He both helped interrogate the North Berwick witches and advised King James on writing his Daemonologie (1597).

Macbeth’s three weird sisters, as imagined (ca. 1783) by the painter Henry Fuseli.

Image: public domain

Weird Sisters

Written a few years before he authorised the Bible translation with which King James has become synonymous, Daemonologie contains three philosophical dialogues that deal with demons, magic, sorcery and witchcraft. The work explains why it is right that witches should be persecuted in a Christian society.

It is thought that Shakespeare used Daemonologie as source material for Macbeth (1606) – set in Scotland and featuring three Weird Sisters – witches whose rituals and quotes would not altogether have been out of place in Newes of Scotland.

Daemonologie influenced later witchfinders (and their manuals), including Richard Bernard (A Guide to Grand-Jury Men, 1629) and Matthew Hopkins (The Discovery of Witches, 1647).

The Witchstone in Dornoch marks the presumed spot where the last witch in Britain was executed.

Image: © JThomas, geograph.co.uk – CC BY-SA 2.0

A witch in the garden

Women had been persecuted as witches for much longer than the period described by this map; but its end date coincides with the end of government-sanctioned witch-hunting.

Executed in 1722, Janet Horne was the last person to be legally killed for witchcraft in Scotland – and in fact the entire British Isles.

Janet, who was showing signs of senility, and her daughter, who suffered from deformities on her hands and feet, were turned in to the authorities by their neighbors.

They accused Janet of riding her daughter to the Devil, to have him shod her like a pony. Both mother and daughter were quickly found guilty by the local sheriff, who sentenced them to be burned at the stake.

The daughter managed to escape, but Janet was stripped, tarred, paraded through town and burned alive. The Witchstone, in the private garden of a house in Carnaig Street in Dornoch (Sutherland) still marks the presumed spot of her execution.

Strange Maps #1016

Got a strange map? Let me know at [email protected].