Can’t find the Middle East on a map? Here’s why.

Image: Morning Consult

- If the Middle East is easier to find in the news than on the map, there’s a good reason for that.

- The term is a fairly recent invention with myriad definitions and applications.

- In some versions, it extends further west than Ireland and as far north as Copenhagen.

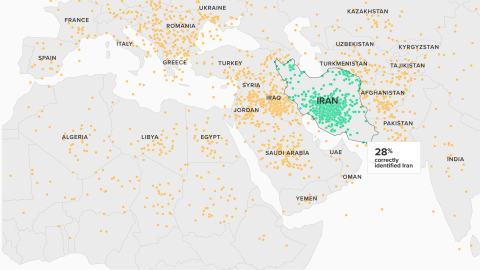

A recent Morning Consult/Politico survey found that fewer than 3 in 10 registered voters were able to identify the Islamic Republic of Iran on an unlabeled world map.

Image: Morning Consult

(Not) finding Iran

At the start of January, as America’s assassination of Iran’s general Qasem Soleimani brought the two countries to the brink of war, there it was again: proof that most Americans can’t find their #1 foreign enemy on a world map.

Asked to locate Iran on a blind map, only 28% of registered American voters surveyed were able to place a dot inside its borders.

- While many picked a location in neighboring Iraq—a forgivable mistake—or stayed in the vicinity of the Islamic Republic, many others strayed much further from their intended target.

- The map shows the Balkans peppered with dots, with various countries in North Africa getting their share.

- The furthest guesses landed as far apart (and away from Iran) as Ireland and Sri Lanka.

It’s an easy and oft-repeated trick: previous versions of the ‘Most Americans can’t find’ map feature North Korea, Afghanistan and Iraq. The subtext is not hard to fathom, and the cause of much sniggering in the rest of the world: Americans are dumb; too dumb to trust with the firepower that comes with being a superpower.

That is of course not true, or at least not proven by these maps. What they do prove is that many Americans are unfamiliar with world geography. A similar survey some years ago showed that one in five Americans were unable to locate the United States itself on a world map.

While that may sound shocking to those who value geo-literacy, it is questionable whether citizens of other countries would do any better. Perhaps they’re just not asked these questions because the likelihood of a shooting war with a faraway, non-neighboring country is rather smaller in, say, Austria or Botswana.

Suez to Singapore: the original ‘Middle East’, as conceived by Alfred T. Mahan.

Image: University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (UNC)

Suez to Singapore, via the Persian Gulf

With Iran’s location on the map up for scrutiny, a much more interesting question surfaces about the region in which it is usually included: Where is the Middle East? That may seem like a strange query for a conflict zone that has dominated global news headlines for the better part of a century. But as these maps show, the definition and the borders of what we think of as the ‘Middle East’ are quite changeable and have evolved over time.

As the term itself indicates, the ‘Middle East’ lies somewhere halfway between the ‘Near East’ and the ‘Far East’. The ‘here’ in that assumption is Europe, and more specifically Britain. ‘Middle East’ is of more recent coinage than its two adjacent denominations, and of surprising origin. The term was invented in 1902 by an American.

Alfred Thayer Mahan (1840-1914) served as a naval officer on the Union side during the Civil War, later rising to the rank of captain in the U.S. Navy. After his retirement, he became a lecturer and historian of naval strategy, gaining worldwide renown with The Influence of Sea Power Upon History (1890) and following books on the topic. His thinking was influential on the development of the pre-WWI naval strategies of the U.S., Britain, France, Japan and Germany.

In an article in the National Review titled ‘The Persian Gulf and International Relations’, Mahan used the term ‘Middle East’ to designate an area along the sea route from Suez to Singapore, including the Persian Gulf. The route was of critical importance for the then British Empire and Mahan urged the British to strengthen their naval power in the area for just that reason.

Mahan’s proposal of the term ‘Middle East’ found wider purchase when it was picked up by Valentine Chirol, writing for The Times.

- In 1903, Chirol published The Middle Eastern Question, in which he defined the Middle East as “those regions of Asia which extend to the borders of India or command the approaches of India, and which are consequently bound up with the problems of Indian political as well as military defense;” i.e. the shores of the Persian Gulf, plus the rest of Iraq and Iran, Afghanistan, and even Tibet, Nepal and Bhutan; as well as Kashmir.

Mirages of the Middle East: Chirol, 1903 (top left), the Royal Geographic Society, 1920 (top right), the RAF, 1939 (bottom left) and British army’s Middle East Command, 1942 (bottom right).

Images: University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (UNC)

When Kenya was in the ‘Middle East’

- In 1920, Britain’s Royal Geographic Society attempted to codify the term, taking the Bosporus as the divider between the ‘Near East’ (i.e. the Balkans; in blue) and the ‘Middle East’ (Turkey to Afghanistan, all the way down to Yemen, and everywhere in between; in red).

- In the years leading up to WWII, the Royal Air Force conceived of the ‘Middle East’ as an entirely different place: it was the land bridge from the Mediterranean to the Indian Ocean formed by Egypt, Sudan and Kenya. All lands under British dominion, providing a safe air corridor between Europe and Britain’s possessions further east.

- A few years later, during WWII itself, Britain’s ‘Middle East Air Command’ expanded that definition to include all the countries in the Horn of Africa (Eritrea, Ethiopia, Djibouti, Somalia), the port possession of Aden (the red dot in Yemen), the countries stretching from the eastern Mediterranean to India (Palestine, Lebanon, Syria, Transjordan, Iraq and Iran), plus Libya and… Greece. That jars with today’s conception of the Middle East, but it made sense from an operational point of view during the war.

A more contiguous ‘Middle East’, as defined by the Brits after WWII.

Image: University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (UNC)

A contiguous ‘Middle East’

By 1952, the official British definition of the ‘Middle East’ was ‘cleaned up’. Henceforth, the concept stood for a geographically contiguous (if not culturally homogenous) region.

Out went Greece and Kenya, at the northern and southern extremities. In came the countries of the Arabian Peninsula (Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Qatar, Bahrain, Oman, Yemen) and Afghanistan.

Oh, and look: Cyprus is in there as well—not unimportantly, as Britain had (and still has) two major military bases in the island, which have often been used since then for British military operations in the region.

Various definitions of the region, all including the nations of the Arabian Peninsula, most excluding Israel.

Image: University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (UNC)

Various definitions

Various international organizations have widely different definitions of the ‘Middle East’. Some examples, all from 2005:

To prevent the dilution of international labour standards by ‘regionalism’, the International Labour Organization (ILO) preferred to organize its regional offices for entire continents. Yet in 1985, the ILO created a regional office for the Arab states which by 2005 covered the countries shown on the map top left (in yellow).

These countries are still treated as part of the Asian department when regional conferences are convened. As is often the case with international organizations, Israel is excluded from the regional grouping in order to avoid acrimony and instead is added to ‘Europe’.

The ILO definition of the ‘Middle East’ is one of the narrowest, excluding Egypt, Turkey, Iran and lands beyond. It is also the most consistent, as it overlaps entirely with the areas covered by other organizations, widely varying as their extremities may be.

On the map top right, the countries in darker blue are part of the ‘Near East’ region of the Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO) when it comes to council elections. The FAO’s definition of the region is wider when it comes to its activities and projects, in which case it also includes the countries in lighter blue (incl. Pakistan, Kazakhstan, Turkey and Mauritania).

In 1957, the World Bank replaced its department for Asia and the Middle East with three new departments: for the Far East, South Asia and the Middle East. In 1967, the latter was enhanced with the countries of North Africa, creating the MENA region (Middle East/North Africa). In 1968, the departments for MENA and Europe merged (EMENA), only to be re-divided, into Europe and Central Asia and, again, MENA—stretching from Morocco to Iran, and from Syria to Djibouti (map bottom left).

In 1948, the World Health Organization (WHO) established the ‘Eastern Mediterranean’ as one of its six global regions. It extended from Greece east to Pakistan (not including Afghanistan) and south to Yemen (not including Oman). In Africa, it took in Egypt, the Tripolitania area of present-day Libya, and the countries of the Horn.

By 2005 (as shown on the map bottom right), Greece and Turkey had been transferred to ‘Europe’; and Ethiopia, Eritrea and Algeria to ‘Africa’ in 1977. Morocco had preferred to remain in ‘Europe’, and was transferred to the ‘Eastern Mediterranean’ only in 1986. Oman and Afghanistan have now also been added to the ‘Eastern Mediterranean’. Israel joined the WHO in 1949, but met with non-cooperation in the ‘Eastern Mediterranean’. It was transferred to ‘Europe’ in 1985.

Evolution of the State Department’s definition of the ‘Near East’.

Image: University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (UNC)

When east is west

After the Brits had relegated the term ‘Near East’ to the Balkans as a prelude to forgetting about it altogether, the Americans decided to adopt it for their own official use.

- In 1944, the U.S. State Department’s Office of Near Eastern and African Affairs had three divisions (top map).

- The African one (in yellow) covered all of Africa, minus Algeria (supposedly considered part of France, hence ‘European’) and Egypt.

- Egypt was part of the Division of Near Eastern Affairs (in blue), which covered an area from Greece to Turkey and Iraq, and the entire Arabian Peninsula.

- To the east lay the area covered by the Division of Middle Eastern Affairs (in red): from Iran to Burma, and everything in between.

- In 1948, presumably after (and because of) the independence of India and Pakistan, the State Department renamed the division covering region from Afghanistan to Burma the Division of South Asian Affairs. Sudan was moved from African to Near Eastern Affairs. Greece, Turkey and Iran were shoehorned in the new Division of Greek, Turkish and Iranian Affairs.

- In 1992, the State Department divided the Bureau of Near Eastern and South Asian Affairs in two. The new Bureau of Near Eastern Affairs jettisoned Sudan (which reverted back to the African desk), but absorbed Iran and the remaining nations of North Africa. Curiously including Morocco, which is more to the west than Ireland, into the ‘Near East’.

Scholars tend to take a maximalist approach to the ‘Middle East’.

Image: University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (UNC)

Scholarly approaches

Scholarly approaches in the U.S. to what constitutes the ‘Middle East’ tend to be maximalist but show interesting variations nonetheless.

Founded in 1946 in Washington DC, the Middle East Institute (MEI) aims to increase knowledge of the Middle East among Americans, and to promote understanding between people from both places. In the very first issue of its Middle East Journal (1947), it printed this map as its definition of the ‘Middle East’ (map top left).

- In Africa: Morocco to Somalia and all the countries in between, including Ethiopia.

- The ‘middle’ Middle East: everywhere from Turkey down to and including the Arabian Peninsula, the Caucasian countries (Georgia, Armenia and Azerbaijan).

- Places further east: Not just entire countries—Iran, Afghanistan, Pakistan and India—but also the Muslim-influenced parts of Central Asia that were then part of the Soviet Union and China.

In 2005, the Middle East Journal published this revised map of the ‘Middle East’ (map top right).

- In Africa, it now includes Mauritania—but not the Western Sahara, illegally occupied by Morocco. No longer included: Eritrea, Ethiopia and Somalia.

- Djibouti is the only country in the Horn of Africa that’s still on board.

- Further east, India (and Bangladesh) have been left out, as have the Muslim areas of eastern China. The ‘Middle East’ has expanded north to include all formerly Soviet Central Asian state, up to and including Kazakhstan—meaning the Middle East extends to about the same latitude as Copenhagen.

The current website of the Middle East Institute offers a slightly different take: plus Western Sahara, minus South Sudan and Djibouti, minus the Caucasian republics, and apparently minus the Central Asian states.

In 1970, the Middle East Studies Association (MESA) in its International Journal of Middle East Studies defined its geographical area of interest (map bottom left) to include “the countries of the Arab world from the seventh century to modern times”.

Also included: territories which were “part of Middle Eastern empires or were under influence of Middle Eastern Civilization,” such as the Iberian Peninsula, the Balkans, up to central and southern Ukraine, the entire Caucasus area and significant areas of Central Asia, up to Pakistan.

In 2000, MESA updated its geographical scope, expanding it into the northern part of present-day India (map bottom right).

**maybe she’s born with it**

**maybe it’s the Arab world** pic.twitter.com/tlG2l4LJcz— Ted Bey (@TedBey) January 10, 2020

Poetry over politics

Except for the very first image, all the maps in this post are from a Twitter thread by Amro Ali, a sociology professor at the American University in Cairo. Replying to the various cartographic definitions, someone responded with an image that literally personifies the region: Arab Lady, her hair the shape of the Arab world. (In fact, coterminous with the member states of the Arab League).

And you can’t argue with Arab Lady, because poetry of place always wins against the prose of politics.

Strange Maps #1007

Iran dot map found here at Morning Consult. All other maps found via Amro Ali’s Twitter. All those from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, except the Arab Lady, viaTed Bey’s Twitter.

Many thanks to Robert Capiot for pointing me to Mr Ali’s maps.

Got a strange map? Let me know atstrangemaps@gmail.com.