The joy of French, in a dozen maps

- Isogloss maps show what most cartography doesn’t: the diversity of language.

- This baker’s dozen charts the richness and humour of French.

- France is more than French alone: There’s Breton and German, too – and more.

Most maps show physical features and political divisions, but there’s a special subset of cartography that reveals language as an exciting, unpredictable layer of human geography.

These are called isogloss maps, because they illuminate regions that share similar linguistic traits. Those traits sometimes echo the landscape or the history of the area they depict – and sometimes they appear to be completely random.

That mutability is one of the main attractions of isogloss maps, as Mathieu Avanzi surely will agree. He is the creator of these maps (and many more like them), that chart the diversity, the richness and the humour of the French language.

You can find them at his website, Français de nos regions (mapping French regionalisms) or in his Twitter feed. Here’s an amuse-bouche, assembled for your enjoyment. Bon appétit!

Don’t fall off the va-gong

In both English and French, a ‘wagon’ is a vehicle – mainly horse-drawn in English, exclusively rail-bound in French. An English wagon is used for transporting goods, and occasionally people. A French wagon never carries people; that’s a ‘voiture’.

Although French seems to have a clearer idea of what a ‘wagon’ is supposed to be, it’s in two minds on how to pronounce the word. In most of the Francophone world, the common practice is to say something like ‘va-gong’ (in blue). In a much smaller part of the French language area – essentially, French-speaking Belgium – the popular pronunciation approximates ‘wa-gong’ (in red). There’s a narrow fifty-fifty zone just across the French border (in white).

French has a habit of dealing poorly with the “w” sound at the start of words, which are often Germanic loan words. It’s produced English word pairs of similar origin with different shades of meaning, such as guarantee (a promise to assume responsibility for something) and warranty (a written, formal version of a guarantee); or warden (a keeper) and guardian (a protector).

Shut the door already

If you’re an English-speaker who wants to express their deep admiration of a French-speaker, just say “Shut the door”. That’s close enough to Je t’adore (“I adore you”). If you want that French speaker to actually shut (and lock) the door, the options are a bit more varied.

- In most of France, the rather matter-of-fact request would be: Fermez à clef:“Close (the door) with the key”.

- In the Loire Valley, plus bits of Normandy and Artois, further north (in blue), you’d have to ask: Barrez (la porte): “Bar the door”. Which suggests that surviving the night depends on a firm obstacle to keep the bandits outs. Which may have been true, not that many centuries ago.

- In the Lorraine area in the northeast and in most of Normandy, your best bet would be to ask: Clenchez (la porte). In the Belgian province of Luxembourg, the variant is: Clinchez (la porte). Sounds like an anglicism, and indeed, some dictionaries refer to this as an expression used in Québec.

- In the départements of Aveyron and Lozère, you may have to ask: Clavez (la porte). (‘Claver’ is related to ‘clef’, key), with smaller areas insisting on crouillez, ticlez or cottez (la porte).

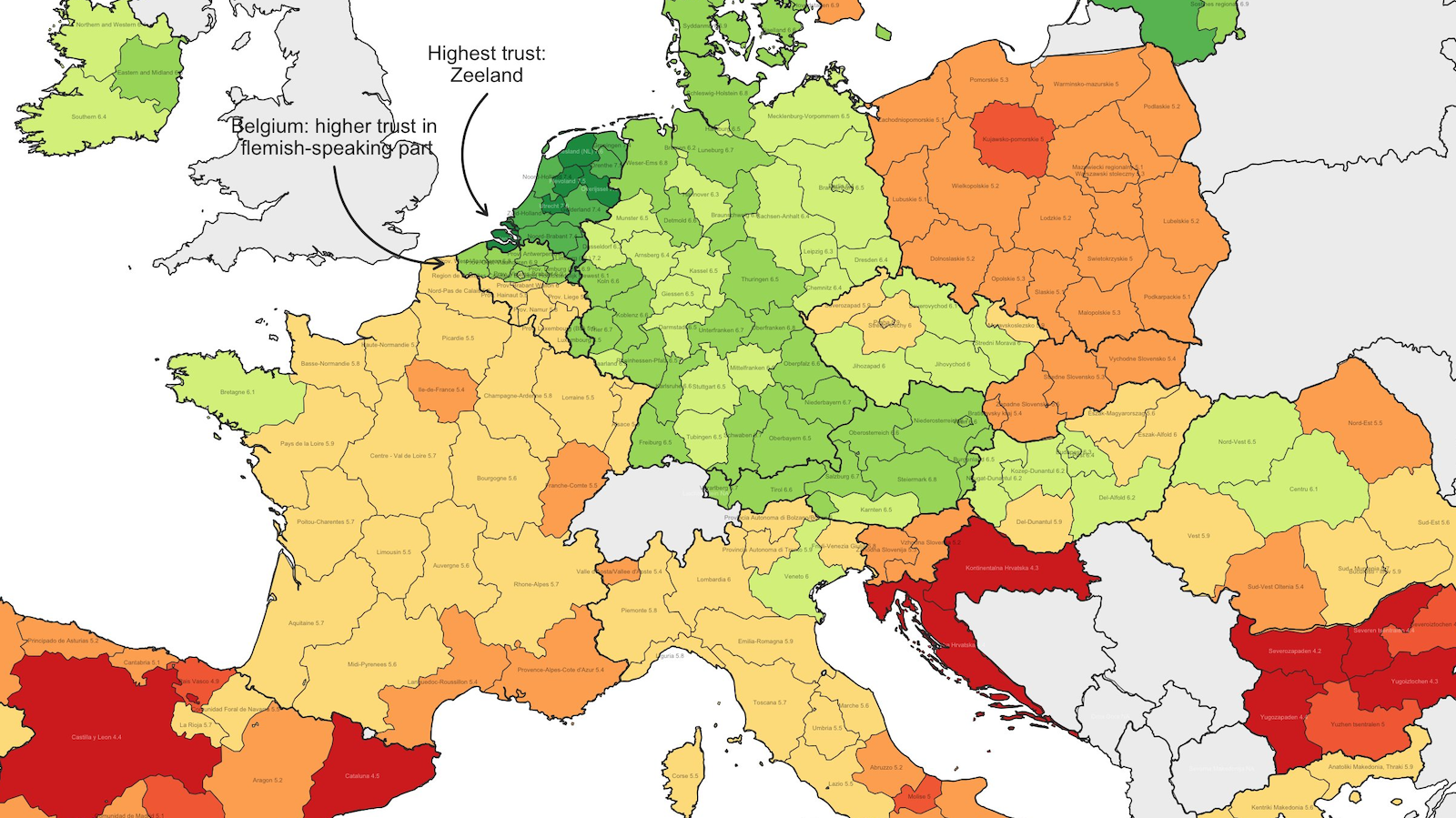

Sharpen your pencils

The humble pencil has more than half a dozen appelations across the French language area. In Belgium and the Alsace, it’s a simple crayon. But in most of northern France, it’s a crayon de papier, while in most of southern France, it’s a subtly different crayon à papier; although there are pockets of de/à dissenters in both halves. Sprinkled across the rest of France (and Switzerland) are small islands, where the locals insist a pencil is a crayon de bois, or a crayon papier, or a crayon gris.

How did the same variant emerge in areas so far apart? Was perhaps the whole Francosphere once crayon gris territory, only for it to be beaten back to the periphery by newer, more aggressive strains of crayon? The smallest, most isolated island is the crayon de mine zone astride the Aisne and Marne departments. Beset on all sides by three other variants, it is only a matter of time before it falls to one of its besiegers – the question is, which one?

Foot-fingers and lexical poverty

The French language is an excellent vehicle for complexity and subtlety, be it poetic or scientific. But it doesn’t have to be. Take this map, which collects vernacular descriptions for ‘toes’.

The information was collected in the 19th century – hence the non-inclusion of Brittany and Alsace, where the majority at that time still spoke Breton and German, respectively. Also note the white spot in the middle: this is Paris and environs. Of course, these locals speak proper French. No need to do any research here.

In most of France, the common word for toe is orteil. Which is the one still used today. One area, half in southern Belgium and half in northern France, insists on calling toes doilles. But in some areas, in the northeast and southwest especially, people use the descriptor doigts de pied, which literally translates as: ‘foot-fingers’. It’s a shocking indicator of lexical poverty. What did these people call their nose: ‘face-finger’?

Sixty-ten or seventy?

French famously doesn’t have a dedicated word for ‘seventy’. Instead, the French use soixante-dix (‘sixty-ten’). But that hasn’t always been true – nor is it true everywhere.

As indicated by the red triangles on the map on the left, septante (or setante) was dominant in much of the southern, eastern and northern areas where French was spoken. Fast forward to now (map on the right), and modern education and media have done their work.

Both in France, where soixante-dix has won the battle, and in the Francophone parts of Belgium and Switzerland, where septante has retained its local dominance. The Belgians and Swiss also say nonante for ninety, by the way, while the French seem to think quatre-vingt-dix (‘four times twenty plus ten’) sounds better.

Le Wite-Out or La Wite-Out?

When writing was still mainly a matter of ink and paper, corrector fluid was the analog version of the backspace key. Americans may know it under the brand name Wite-Out. In the UK and Europe, the corresponding corporate designation was Tipp-Ex. And that’s what Parisians, Belgians, Swiss and the inhabitants of Alsace and Lorraine also call it.

A swathe of eastern France corresponding roughly with Burgundy calls it, simply, blanc (‘white’) – without the final -o that gives it the product a slightly exotic flourish in the rest of France.

The graph to the left of the map indicates the preferred terms in French Canada: mostly Liquid-Paper (another brand name), sometimes also its French translation papier liquide, and Wite-Out or, simply, correcteur.

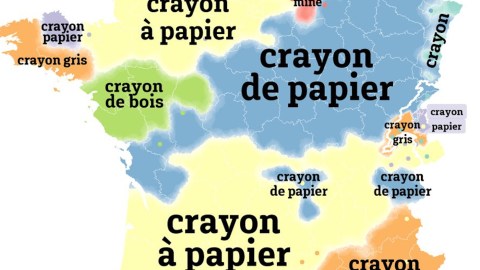

Pitcher perfect

It’s a warm day, and/or the food itself is too hot. How do you ask your French waiter for a pitcher of water? This map will tell you.

In Paris, and various areas in the center and south of France: un broc, s’il vous plaît. In the northeast: une chruche. In the north and west: un pichet. In various parts of the south: une carafe. Or un pot à eau, if not un pot d’eau. In case you don’t have this map handy: there’s just one word for wine: vin.

Case of the melting mitten

‘Mitten’ is such a common English word that its foreign origin comes as a surprise. It is from the 14th-century French word mitain, for ‘hand-covering, with only the thumb separated’.

While the word has flourished in English, it has melted away in its native France. The standard French term for ‘mittens’ these days is moufles.

Mitaines survives as a regionalism, in the Charente region, the hinterland of the port city of La Rochelle; and in parts of Francophone Switzerland.

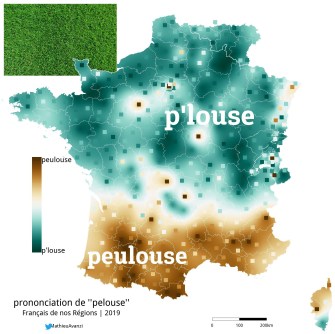

Your pelouse or mine?

France – and French – used to be characterised by a deep split between north and south. The north was the land of butter and beer, the south of olive oil and wine. In the north, in the past often referred to as ‘Langue d’ouïl’, the common way to say ‘yes’ was the current standard term, oui. In the south, today often stlll called ‘Languedoc’, the local version of ‘yes’ was oc.

While the edges of France’s great north-south divide have softened, there are still traces to be found, in culture and language. Take for instance the pronunciation of pelouse (‘lawn’). Northern French will have you believe the word is p’louse (‘plooz’), while southern French will take the time to pronounce the entire word, as peulouse (‘puh-looz’).

It is possible that name for the Palouse, the region in the northwestern US, was provided by French trappers, impressed by its rolling grasslands. A more common French loanword for grasslands is, of course, prairie.

France is not all French

The French language is essential for France’s understanding of itself as a nation, yet for much of its history, the nation was not contiguous with the language. Some parts of the French language area are (and mostly always have been) outside the French borders, notably in Belgium and Switzerland. French language and culture is also significantly present in Luxembourg, northern Italy and the Channel Islands.

Conversely, while most of France now speaks French as its first language, other languages have historic significance (and lingering presences today) at the nation’s extremities: Flemish in the north, German in the northeast, Breton in the west and Basque in the southwest, to name the most familiar non-Romance ones.

What survives in daily use are local expressions, like these three Breton words. Louzhou is used at the very tip of the Breton peninsula as a synonym for ‘herb, medicine’. Kenavo has a wider purchase, across three and a half departments, and means ‘goodbye’. Bigaille is understood down to Nantes and beyond as slang for ‘small change’.

As a conversational vehicle for daily life, German in Alsace and elsewhere in eastern France is moribund, if not already dead. But a bit of Deutsch survives nonetheless, for example in Ca gehts?, the curious local portmanteau for “How are you?” – composed equally of the French “Ca va?” and the German “Wie geht’s?” Another Germanic survivor: the term “Schnapps”. In the rest of France, it’s called “Eau de vie” (“Water of life”).

All images reproduced with kind permission by Mathieu Avanzi. Check out his website and/or his Twitter feed, both focusing on isogloss maps of French, in France and beyond.

Strange Maps #1006

Got a strange map? Let me know at strangemaps@gmail.com.