GPS jamming, a weapon in hot and hybrid wars, will soon be obsolete

- Electronic warfare has become standard in the world’s conflict zones.

- GPS jamming confuses enemy missiles but can be deadly for civil aircraft.

- Solid-state gyroscopes could soon render the practice obsolete — but that’s not all good news.

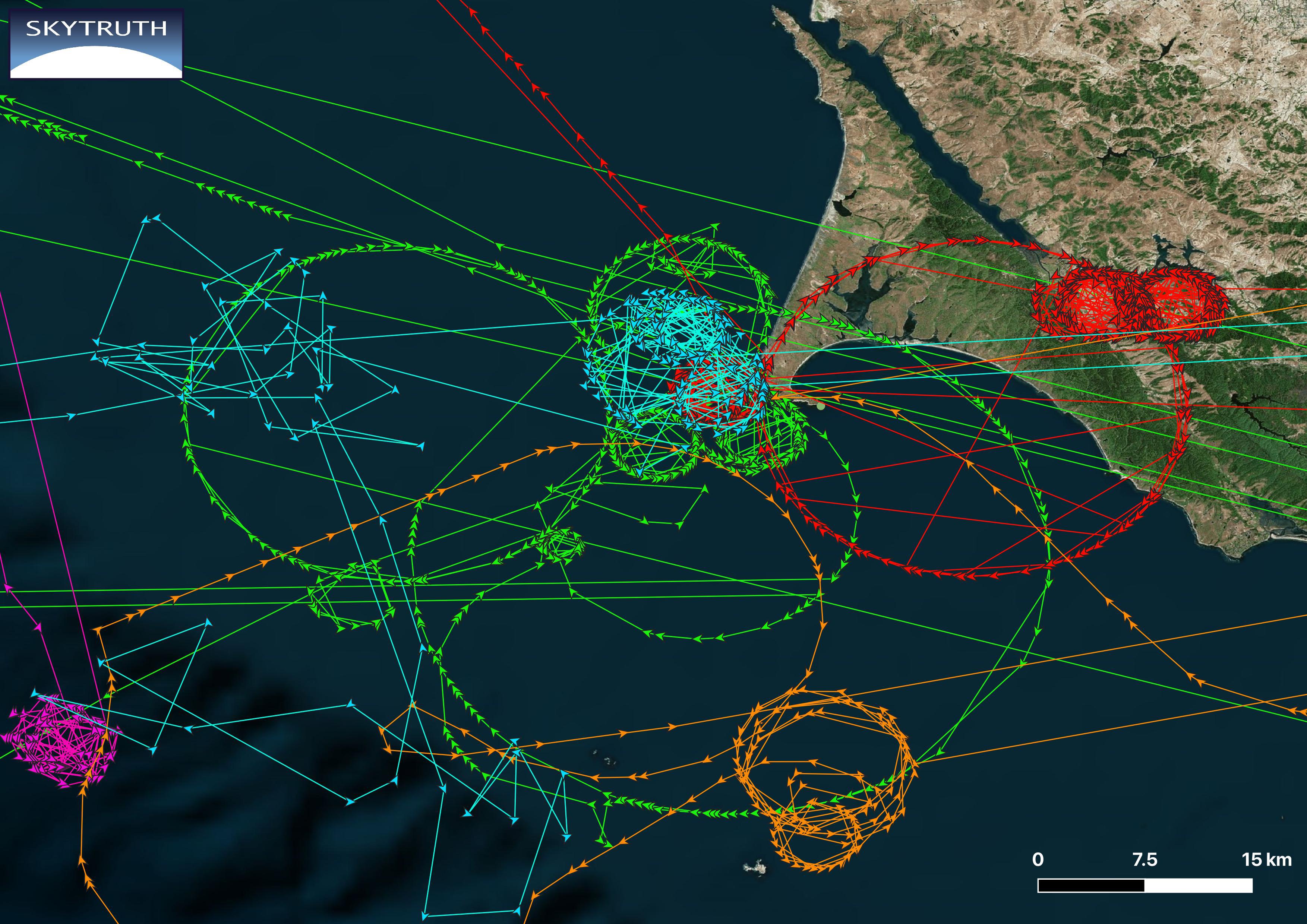

This may look like a weather map, but what it shows isn’t your usual kind of atmospheric interference. The red hexagons denote areas affected by GPS jamming in the preceding 24 hours.

GPS jamming, which disables the positioning system of electronic devices, including those used to locate aircraft, can be anything from inconvenient to deadly. It played a part in the Christmas Day crash of Azerbaijan Airlines 8243 in western Kazakhstan, killing 38 passengers and crew.

As the geographical distribution of the red hexagons suggests, GPS jamming occurs mainly in and around the world’s conflict zones.

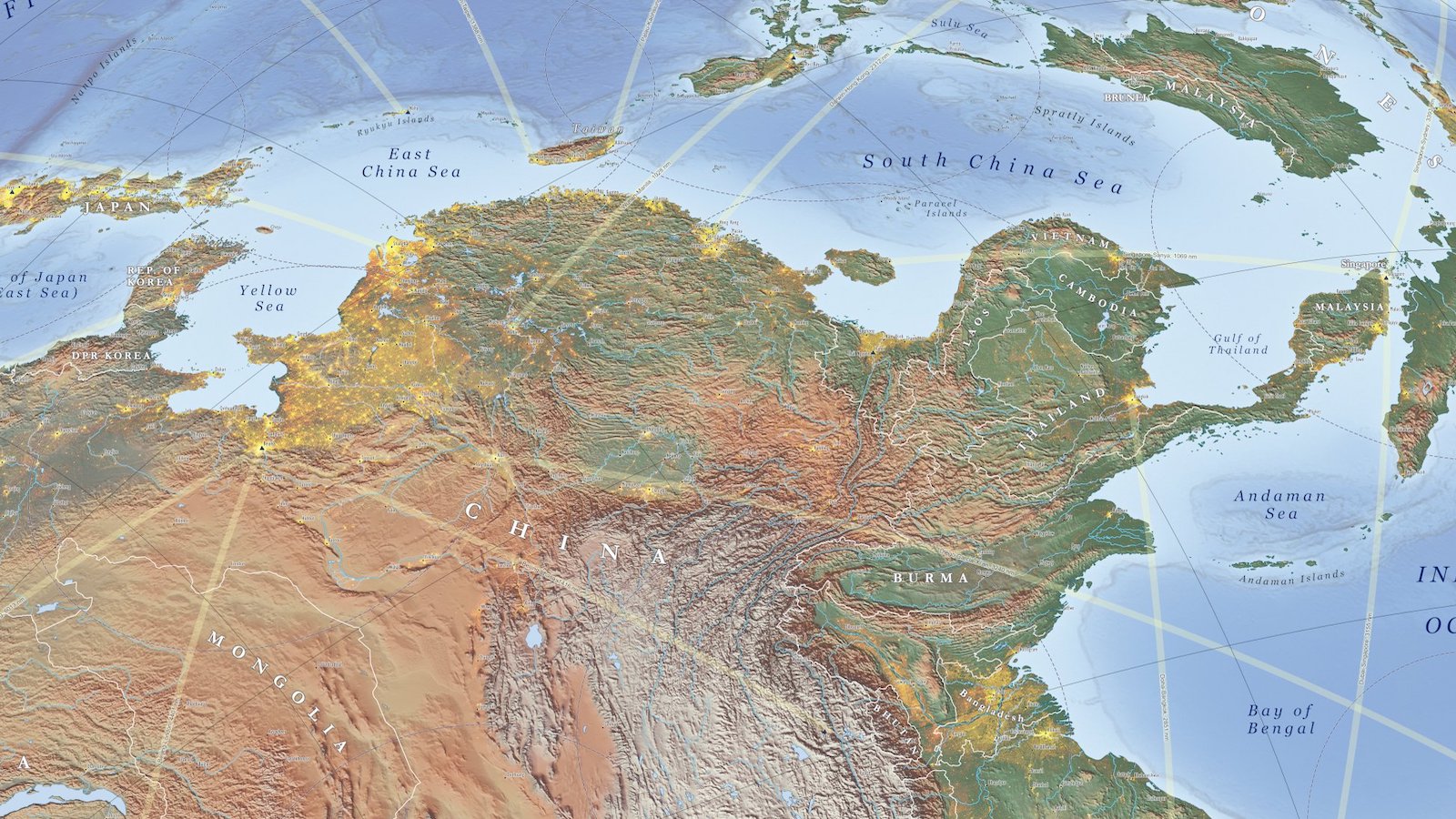

Red dominates the skies over and near European Russia and the Black Sea — basically, around Ukraine; over large parts of Turkey and the Middle East; across the Caucasus and the Caspian Sea, which was the area of the Azerbaijan Airlines crash; and farther east, above Indian-administered Kashmir, and in Burma/Myanmar, home to the world’s longest-running civil war, since 1948.

According to this snapshot, GPS jamming is not much of an issue in the rest of the world. At other times, however, the “GPS weather” on this map, provided by flight tracking specialists FlightRadar24, will show some jamming near the U.S.-Mexico border. There are also frequent reports of jamming by North Korea to its south, and by China toward Taiwan.

Whether in hot or hybrid wars, GPS jamming is one of the most popular forms of electronic warfare. So what exactly is it?

GPS jamming

To understand how dependent today’s aviation is on GPS, it’s worth going back to when it wasn’t, less than a century ago. There were no satellites in 1927 when Charles Lindbergh went on his record-breaking non-stop solo flight across the Atlantic. He only had a compass to navigate by, using dead reckoning to calculate his position. When he reached Dingle Bay in Ireland, the first dry land since Newfoundland, it turned out his calculations had only been off by three miles — a feat almost as impressive as the flight itself.

While accurate enough for the relatively airplane-free skies of the 1920s, today’s aircraft need to be much more precise about their position — and they are, thanks to satellites and the signals they send.

Modern aircraft use this Global Positioning System (GPS) to know and broadcast their position. Or, more precisely, they use something called the Global Navigation Satellite System (GNSS), which includes not just America’s GPS, but also similar systems worldwide, such as Europe’s Galileo, Russia’s GLONASS, and China’s BeiDou.

Signals from these satellites help pinpoint the exact geographical position of a receiver aboard an aircraft, which then communicates that position to ground stations and other aircraft.

That is, if all goes well. Solar storms can interrupt or degrade GNSS signals. More dangerous, and increasing in frequency, are human-made, malicious disruptions and distortions of the signal.

One type of these human interventions is GPS jamming: saturating the receivers with junk signals, making it impossible to use GPS (or GNSS) to navigate the aircraft. (Another is GPS spoofing, which tricks the receiver into transmitting a false location, sometimes with bizarre results — see Strange Maps #1074).

GPS jamming is inconvenient for aviation, but generally not prohibitive. Aircraft use satellite positioning together with other systems to determine their position, specifically WAAS (Wide Area Augmentation System) for general navigation, and GBAS (Ground-based Augmentation System) when approaching airports. Airlines are aware of GPS jamming, and crew know how to use these backup systems to ensure flight safety.

That is because most GPS jamming is not primarily targeted at airplanes. It can be used to disrupt other GPS-dependent missiles and devices, including drones and phones. Russia is using the technique to fend off attacks by Ukrainian drones — and this is reportedly what occurred over Grozny as the Azerbaijani passenger jet was preparing to land, likely leading it to be confused with an enemy projectile.

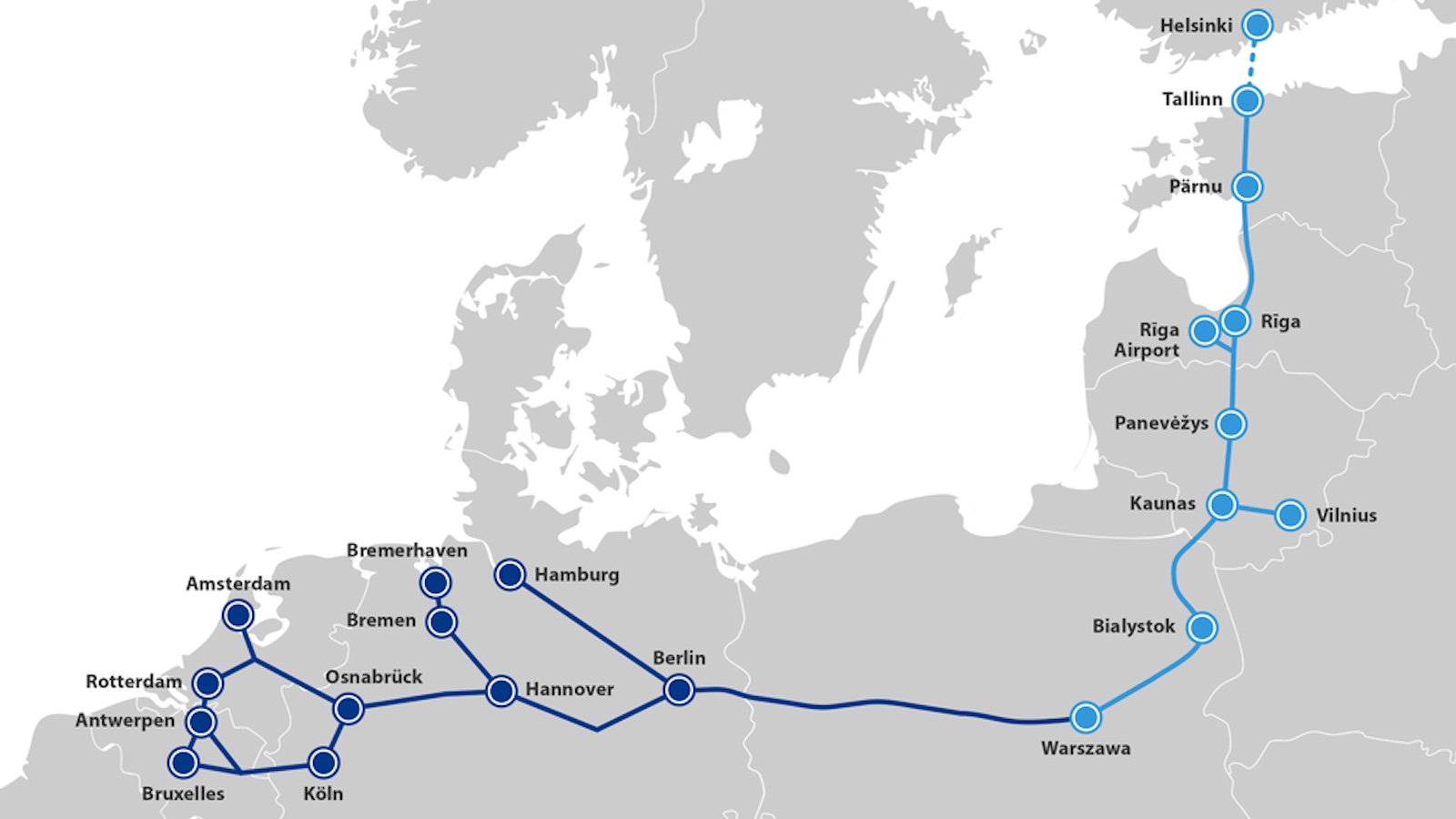

However, Russia appears to be using GPS interference not just internally, to disable enemy attacks on its territory, but also externally, as part of its hybrid “shadow war” against Europe, to make an electronic nuisance of itself. Some examples:

- In 2022, Finland was hit by GPS interference immediately after a meeting between its president and his U.S. counterpart, former President Joe Biden, on the topic of Finland joining NATO.

- In 2023, after Poland activated an anti-missile system near the Russian exclave of Kaliningrad, GPS signals in the country’s north were affected by jamming and spoofing attacks.

- By mid-2024, GPS jamming in Norway’s northern region of Finnmark had become so widespread that authorities stopped logging incidents, and have accepted them as the “new normal.”

- On December 12, 2024, Bulgaria and Romania joined Schengen, the Europe-wide, visa-free travel zone. Immediately after, the Bulgarian capital Sofia was subjected to GPS interference.

GPS interference also was a factor in Israel’s recently paused war with Hamas in Gaza and Hezbollah in Lebanon. The practice, used to confuse incoming enemy missiles and drones, also impacted thousands of civilian flights — not just those departing and arriving locally, but also others merely passing through.

This type of electronic warfare can have unintentionally surreal and/or hilarious consequences. One Beiruti Uber driver recently reported suddenly finding himself in the Gaza Strip — at least according to his online map application. And the GPS disruptions are also known to have affected dating apps across the Middle East, showing users potential matches in “enemy countries.”

North America currently has no hot or hybrid wars, but the continent isn’t entirely free from GPS interference — or the risk of such problems increasing.

Criminals are using GPS jamming as an aid in drug trafficking and vehicle theft, among other nefarious activities. Occasional GPS jamming and spoofing events have disrupted American airports in recent years. More and more citizens are acquiring jamming devices, as privacy fears and conspiracy theories spread.

The U.S. currently lacks an automated, real-time national detection system for GPS interference, leaving government, emergency, and commercial operations vulnerable to such interference.

One solution could be to turn the more than 300 million smartphones in use across America — “one of the most potent distributed sensor networks on the planet” — into a crowdsourced detection tool for GPS/GNSS interference.

GPS jamming and spoofing have become enough of a nuisance, for civil aviation and other industries, that two tech companies have developed a workaround: a new technology that’s been called a “gyroscope on a chip”.

Traditional optical gyroscopes were a bulky alternative to satellite-based navigation — until 2018 when CalTech scientists figured out a way to reduce a solid-state gyroscope to the size of a grain of rice.

In the last few months, Anello Photonics (Santa Clara, California) and OSCP (Montreal, Canada) have separately introduced inertial navigation devices that don’t require satellite signals to accurately report geographical position and direction.

Both companies are marketing conveniently tiny devices that will benefit not just passenger planes, but also drones, autonomous tractors, and unmanned underwater vehicles in the ocean.

This satellite-free navigation technology will undoubtedly help make civil aviation a little bit safer — while also potentially making military drones a lot deadlier.

Strange Maps #1269

Got a strange map? Let me know at strangemaps@gmail.com.

Follow Strange Maps on X and Facebook.