These 9 U.S. biodiversity hotspots urgently need protection

Image courtesy of Clinton Jenkins

- Biodiversity is essential for ecosystems – and humanity – to survive

- These maps show the diversity of biodiversity itself: the hotspots are all over the place

- Compounding U.S. biodiversity data produces a list of 9 ‘Recommended Priority Areas’, most in need of protection

Bridal Veil Falls in Nantahala National Forest (NC), located in the Blue Ridge Mountains, one of the nine biodiversity hotspots in the U.S. in urgent need of protection.

Image: Jan Kronsell, CC BY-SA 4.0

In urgent need of protection

Thanks to pioneers like John Muir and Theodore Roosevelt, the U.S. has a long and proud tradition of nature conservation. But it could do a lot better. Intricate mapping of America’s unique species shows that its biodiversity hotspots match up poorly with the areas already under protection.

A paper published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (1), identifies nine such hotspots in the U.S. outside current conservation areas that most urgently need protection.

Fish species richness is particularly great in the southeast.

Image courtesy of Clinton Jenkins

Size isn’t everything

The best way to prevent extinction is to protect the habitat of vulnerable species. On the face of it, the U.S. is not doing too bad in that department: it counts more than 25,000 protected areas, which cover more than 14% of the nation’s total land area. They make up around 10% of the entire protected land area worldwide.

But size isn’t everything. “Although the total area protected (in the U.S.) is substantial, its geographic configuration is nearly the opposite of patterns of endemism (2) within the country”, the paper’s authors write.

Endemic mammal species in the U.S. are concentrated in the Deep South, with significant presence in the West.

Image courtesy of Clinton Jenkins

U.S. scores lower than global average

When it comes to specific biodiversity protection, the U.S. scores lower than the global average. Only 7.8% of the Lower 48 is within an area categorised as protected by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN). Worldwide, the figure is 10.3%. However, in stricter IUCN categories (I to IV), the share in the U.S. and worldwide is approximately the same, at around 6%.

Most of America’s protected lands are in the West, whereas most vulnerable species are in the Southeast. The mismatch has historical roots: America’s conservation pioneers set out to protect landscapes, not biodiversity.

Bird diversity is mainly a coastal thing.

Image courtesy of Clinton Jenkins

Over 12,000 endemic species

The paper is a first attempt to remedy that problem. By comparing the geographies of biodiversity and conservancy in the continental United States and factoring in species vulnerability, the paper identifies nine priority areas for conservation.

There are over 1,200 endemic species in the continental U.S. and the authors devised a priority score for each of them, based on the size of their range and the proportion that is unprotected.

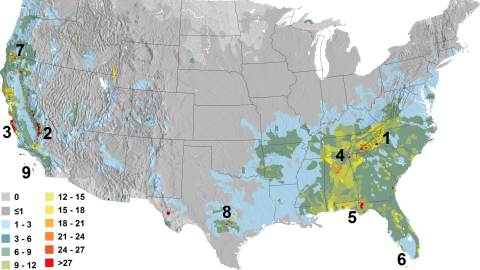

A map of high-priority areas for expansion of conservation in the U.S. to protect the nation’s unique species. It is based on an analysis of multiple groups of endemic species (amphibians, mammals, birds, freshwater fish, reptiles, and trees).

Image courtesy of Clinton Jenkins

Nine Priority Areas

“The highest-priority areas are mostly in the Southeast, California and Texas. (They) cover a relatively small portion of the country but are inordinately important for biodiversity,” the paper says. They are:

- Blue Ridge Mountains (esp. the middle to southern sections, including the Cherokee, Nantahala, Pisgah, and Jefferson National Forests): a major priority for amphibians, mainly due to salamanders, as well as for fish and trees.

- Sierra Nevada Mountains (esp. the southern section): a priority mainly due to amphibians and trees.

- California Coast Ranges: a priority mainly due to trees, amphibians, and mammals.

- Tennessee, Alabama, northern Georgia watersheds: a priority mainly due to its exceptional fish diversity, for which it is globally significant. There is also substantial reptile and amphibian diversity in some areas.

- Florida panhandle: a priority mainly due to trees, fish, and reptiles.

- Florida Keys: a priority mostly due to trees.

- Klamath Mountains (esp. along the border of Oregon and California): a priority mainly due to trees, and somewhat to amphibians, and fish.

- South-Central Texas around Austin and San Antonio: this cluster of sites is a priority mainly due to amphibians, but also fish and reptiles.

- California’s Channel Islands: a priority mainly due to trees, reptiles, and mammals.

Macon, NC is “in the center of global salamander diversity.”

Image courtesy of Clinton Jenkins

Global salamander hotspot

The conservation priority map is one of many biodiversity maps on BiodiversityMapping.org, a website maintained by Clinton Jenkins, one of the authors of the paper. The site also features more detailed biodiversity maps of the United States, Brazil and the world.

“The original inspiration for this site came during the writing of a scientific paper (…) in 2013. (I saw) a need for more widely accessible maps of where the many species on our planet live,” writes Mr Jenkins. “The first maps were for salamanders and other amphibians, created while sitting in the Macon County Public Library in Franklin, NC. That also happens to be in the center of global salamander diversity!”

The maps on the site have been developed by Mr Jenkins, now with the Institute de Pesquisas Ecologicas (IPE) in Brazil, and others.

New Zealand and surrounding waters are a global hotspot for seabird biodiversity.

Image courtesy of Clinton Jenkins

Maps reproduced with kind permission of Clinton Jenkins. For more, check out BiodiversityMapping.org.

Strange Maps #997

Got a strange map? Let me know at [email protected].

(1) ‘U.S. protected lands mismatch biodiversity priorities‘, by Clinton N. Jenkins, Kyle S. Van Houtan, Stuart L. Pimm, and Joseph O. Sexton. Published April 6, 2015, in PNAS.

(2) Endemic species are unique to a defined geographic location.