653 – Charity Ends at Home: the Struggle for 0.7%

“How can we possibly be giving £1 billion a month to Bongo Bongo Land when we’re in this kind of debt is completely beyond me”, Godfrey Bloom said in August of last year. That comment went too far even for the Little Englanders of the UK Independence Party, for which Bloom was then still a Member of the European Parliament.

UKIP forbade Bloom to use the term, a crude stereotype equating the exotic with the primitive (bongo is an Afro-Cuban type of drum; it also sounds like African place names such as Congo). Bloom refused to apologise, merely regretting that his comments had caused offence:

“[Bongo Bongo Land is] a figment of people’s imagination. It’s like Ruritania or the Third World. It’s sad how anybody can be offended by a reference to a country that doesn’t exist […] If I’ve offended anybody in Bongo Bongo Land I will write to their ambassador at the Court of St James.”

UKIP has since ejected Bloom from their group in the European parliament, but only after he called women “sluts” and hit a journalist. He’s been called a ‘wince-inducing gaffe machine’, and even a brief sample of his most offensive statements suggests a mindset firmly to the right of Prince Philip, Queen Elizabeth II’s decidedly undiplomatic consort.

In the alphabetised folder, let’s just look under M for Mysogyny. Bloom is on the record as saying that “no self-respecting businessman with a brain would ever employ a lady of child-bearing age”, suggesting that “women don’t clean behind the fridge enough” and “are better at finding the mustard in the pantry than driving a car”. Please note that Bloom, now an independent MEP, also sits on the European Parliament’s Committee for Women’s Rights and Gender Equality.

In defence of his outrageous statements, Bloom claims he merely voices the opinion of the ‘average man in the street’, whose views are ostracised by political correctness. (The average woman supposedly being too kitchen-bound to even make it to the street). It would seem that he is right – at least as far as his bongo-amplified views on foreign aid are concerned.

In the UK as in other crisis-hit developed countries, foreign aid is an increasingly unpopular item on the annual budget, and an easy target of populist grandstanding. Which is probably why the UK has been very quiet about finally achieving the UN’s foreign aid target.

As revealed by The Guardian earlier this month, confirmation that Britain spent 0.7% of its Gross National Income on Official Development Assistance was buried in a tweet by Deputy Prime Minister Nick Clegg about his meeting with Bill Gates. Yes, it is very difficult to hide information in a message of 140 characters max, but Clegg does a good job of it:

On the day we confirm UK has met 0.7% GNI/ODA, @BillGates and I discussed working together to bust common aid myths.

The 0.7% threshold was adopted in 1970 by a UN General Assembly Resolution, to provide rich countries with a target to spend on helping poor countries develop their economy. Expressed as a fraction of their GNI, the 0.7% sounds like a puny amount for rich countries to spend on charity. But for most it has remained a target – despite regular reminders of their pledge at international aid conferences.

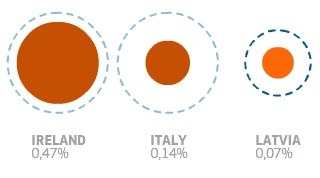

This cartogram provides an overview of sorts of the official generosity of the member states of the European Union.

At first glance, it’s a representation more attuned to represent OCD (Obsessive Compulsive Disorder) than ODA. The EU member states are aligned neatly in three lines of nine dots each, in alphabetical order from top left (Austria) to bottom right (UK). The grand total of 27 is no longer current (Croatia became the 28th EU member state on 1 July 2013), but then the data it represents does refer to 2012.

Each country is represented by two circles, a red one showing the size of its Official Development Assistance relative to a dotted one showing its target. At a glance, it becomes clear which countries are on target, and which are at the back of the class. In fact, on this map (pre Nick Clegg’s tweet), only Denmark, Luxembourg, the Netherlands and Sweden have a red circle larger than their dotted one – i.e. have reached and surpassed the UN’s 0.7% target.

In 2012, the UK with its 0.56% was already closer to that target than any other EU member state, with only Finland also exceeding 0.50%, Belgium, France and Ireland between 0.40 and 0.50%, Germany and Austria stuck well below even that level, and the four economies of southern Europe that were hit hardest by the economic crisis – Greece, Italy and Spain – at between 0.13 and 0.16%.

The names above only include the 15 richer member states from ‘old Europe’. The 12 newer member states, mainly in Eastern Europe, are still on the road to full economic convergence, and have foreign aid targets that are significantly smaller – 0.3% of their Gross National Income. Still, that too is a struggle to achieve. Malta comes closest with 0.23% (thus exceeding the generosity of the aforementioned Mediterranean trio).

Cyprus, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Lithuania and Slovenia all are between 0.10 and 0.13% – which puts them in the Greek league. The others have foreign aid budgets that start two places behind the comma. Poland, Romania and Slovakia each only spend 0.09% of their Gross National Income on ODA, Bulgaria a mere 0.08% and Latvia – the worst student in class – a pithy 0.07%.

According to Godfrey Bloom, foreign aid is wasted on “Ray-Ban sunglasses, apartments in Paris, Ferraris and […] F18s for Pakistan”. In fact, the UN has calculated that the world could halve extreme poverty if the developed world made good on its 0.7% pledge, as the UK has now – stealthily – done. British foreign aid rose by over 30% from 2012 to 2013, totalling £11.4 billion, which is about £180 per person.

Kudos to Britain, but that only makes it the 5th EU member state to get to 0.7%. Sadly, this map shows how charity not only begins, but largely also ends, at home.

Cartogram found on this page of the EU Aid Explorer, at the homepage of the European Commission.