630 – The Silver Dog with the Golden Tail

Five score and seventeen years ago, the United States was a boxy, silver-coloured dog with a chunky tail of dark gold. That bizarre image, embedded in the familiar outline of the U.S. map, is as obscure today as it was poignant during the 1896 presidential election. The question dominating that contest: Would silver trump gold, or would the tail wag the dog? That question makes sense only to economic historians.

As we speed away from it, the past is an increasingly foreign country. National memories become sketchier, anchored only to wars and battles. Thus, we have notions of the causes, casualties and consequences of the Civil War (1861-’65), the Spanish-American War (1898) and the First World War (1914-’18), but hardly an inkling of the titanic struggle between silver and gold that characterised the 1896 election, which in turn dramatically changed America’s political landscape.

It changed it into a silver dog with a golden tail, for the duration of the heated contest between William McKinley, the Republican candidate, and William Jennings Bryan, the Democratic contender. When McKinley trounced Bryan on November 3, 1896, it also meant the victory of gold over silver, the end of farmers as a dominant political constituency and the start of a decades-long stretch of Republican control of the White House. And the silver dog? It vanished, together with its golden tail – both dissolved in the mercury of political irrelevance.

So what was the significance of that dog and its tail? What exactly would the readers of the Boston Globe have chuckled about on September 13, 1896, as they saw this cartoon in their paper?

They would have known about the gold standard – a monetary system in which a paper banknote is freely convertible into a fixed quantity of gold – because it was then in operation in the States, and throughout much of the world. For most of us now, that is a very abstract notion. However, although no country still uses the gold standard to back up its currency, gold itself is still held in reserve, in Fort Knox and similar places elsewhere, as a means to exchange and defend many of those currencies.

In essence, the principle of the gold standard derives from the ancient use of gold, reliably rare and valuable, as a means of payment. The same holds for silver, which nevertheless lost out to gold as the preferred currency back-up, partly due to an increasing abundance of the stuff. The gold sovereign introduced by the Royal Mint at the start of the 19th century formalised the gold standard in Britain, and later throughout the British Empire and beyond. The gold standard was seen as the foundation stone of economic stability, as anchoring money to a limited amount of gold prevents inflation. On the other hand, that same reliance on gold also acts as a damper on growth.

For a long time, the U.S. had a bi-metallic standard, using gold coins for large denominations and silver ones for smaller-value coins. This obviously caused problems when the relative market value of the metals strayed too far from the 15/1 mint ratio (the rate which the government bank was obliged to pay when exchanging silver for gold). Large gold discoveries, as in the California Gold Rush of 1848, caused a chronic overvaluation of gold, which contributed to a crisis of the bi-metallic system and, in 1873, the virtual suspension of silver as a monetary standard.

In the years following this so-called Crime of ’73, the reintroduction of the silver standard would become a political issue, championed most prominently by William J. Bryan during the 1896 presidential election.

Bryan’s speech at the Democratic Convention, one of the least-remembered of great American political speeches, pleaded for the abolition of the gold standard, blaming it for the misery farmers and workers were suffering in a severe economic depression. It is named the ‘Cross of Gold’ speech for its central message: “You shall not press down upon the brow of labor this crown of thorns, you shall not crucify mankind upon a cross of gold”. It was so successful that it delivered the presidential nomination to Bryan – at 36 still the youngest nominee ever.

So-called ‘Bourbon Democrats’, who were pro-business, hence pro-gold standard, fielded their own presidential candidate, John Palmer (at 79 years of age the oldest candidate ever). Bizarrely, the Populist Party, the main ‘third party’ of the time, nominated Bryan, the official Democratic candidate, as their candidate too! They did, however, nominate a different vice presidential candidate. Bryan remained coy about his eventual VP choice, if elected. And that’s not the end of factional weirdness. A group of Republicans from western states, opposed to their party’s gold standard platform, formed a National Silver Party, which nominated – you guessed it – William Jennings Bryan for president!

With three parties supporting his nomination and a nationwide wave of sympathy in the wake of his ‘Cross of Gold’ speech William J.Bryan seemed the likely winner of the contest. But the Republicans collected substantial financial support from businessmen afraid of the destabilising economic effect of Bryan’s pro-silver measures. It was the first – but not the last – time a candidate would appeal directly to business for support, with the promise of favourable results should he get elected. Consequently, McKinley was able to outspend Bryan 5 to 1, in a national campaign portraying himself as the safe pair of hands, and Bryan as a dangerous nutcase whose ‘silverite’ agenda would destroy the economy.

Bryan fought back by going on a speaking tour throughout the Midwest, chalking up 18,000 train miles in 3 months, and speaking directly to 5 million Americans – at one point giving 36 speeches in a single day. The popular surge for Bryan was counteracted by well-orchestrated mudslinging and scare tactics from the McKinley camp.

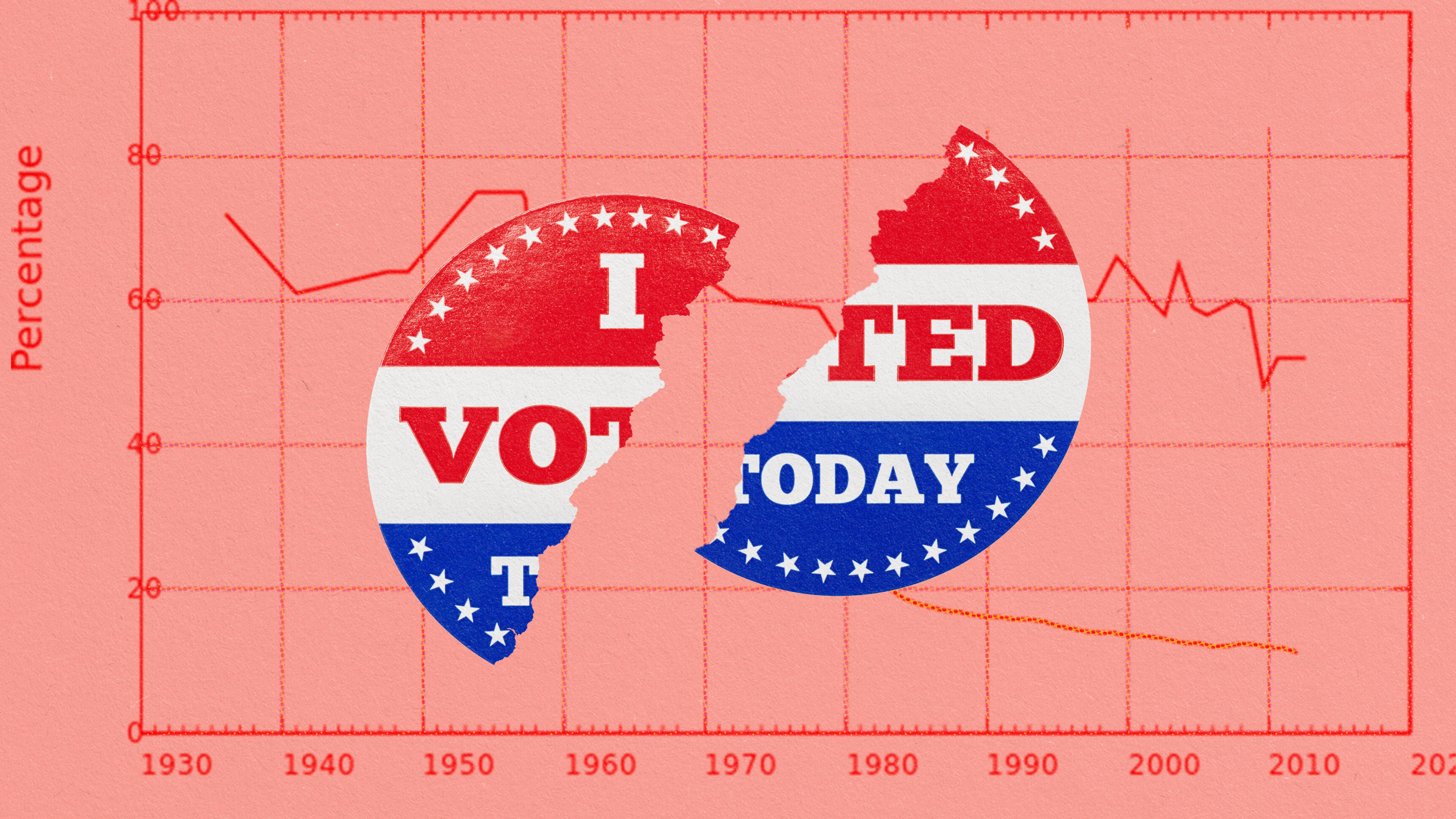

On November 3, McKinley won big among the middle classes and workers in the northeast and midwest, while Bryan scored well among the farmers of the south and west. But the rural vote no longer was enough to win a presidency. In the end, McKinley got 51% of the popular vote (just over 7 million votes) and 271 electoral votes (224 were needed to win) against Bryan’s 47% (6.5 million votes) and 176 electoral votes.

The Boston Globe readers would have recognised this cartoon as an plea for free, unlimited minting of silver coins, thus ending the gold standard’s dominance.

By portraying the (more populous, hence more electorally powerful) northeastern states as a ‘golden tail’ in contrast to the ‘silver body’ of (relatively less populous, less powerful, but more numerous) states in the rest of the country, the Globe is presenting the gold vs. silver question as one of a localised pro-gold elite versus the widespread, pro-silver will of the people.

This is a relatively early example of the expression ‘wag the dog’, which in general can be understood to mean that cause and effect are reversed: instead of the dog wagging its tail, the tail wags the dog. Its more precise, and more widespread use is as a political trope, to express the perverse situation in a democracy when the goals of a minority prevail over wishes of the majority.

McKinley, and the gold standard, might have won in 1896, but that victory would ultimately prove ephemeral.

A few decades later, World War I killed off not just millions of young men and a handful of European monarchies, but also the gold standard. The vast amounts of money needed to finance the war made any pretence of convertibility between paper money and actual gold impossible. In many countries, the forcible abandonment of the gold standard led to runaway inflation. According to some economists, the gold standard contributed to the Great Depression. What is indisputable is that the Depression finished off the gold standard for good.

Image of the dog-wagging tail found here on Authentic History.