550 – The City and the Kitty, and Other Urban Analogies

Surprise meeting with an old acquaintance in the Whitechapel Gallery – Grayson Perry’s Map of an Englishman (discussed in #241). “It’s the work that draws the most people, and gets the most laughs”, said the attendant. No wonder. Perry’s Map is a masterful blend of vaguely Tolkienish fantasy cartography, astute social commentary and dark comedy. It is most rewardingly confronted up close, so you can browse its improbable place-names, trace the links between its geo-located neuroses, and travel between neighbourhoods named for the hobbies and sins of Perry’s idealised (if hardly ideal) Englishman.

Sadly, no facsimile in the Gallery’s bookshop. But they did have O.M. Ungers’ Morphologie/City Metaphors. Even flipping through it once, I knew I had to have it. But perhaps a less bent and used-looking copy? “Sorry, last one. And going out of print fast”, said the lady behind the counter, sensing my eagerness. So I forked over a tidy sum for the presumed rarity [1]. How could I not?

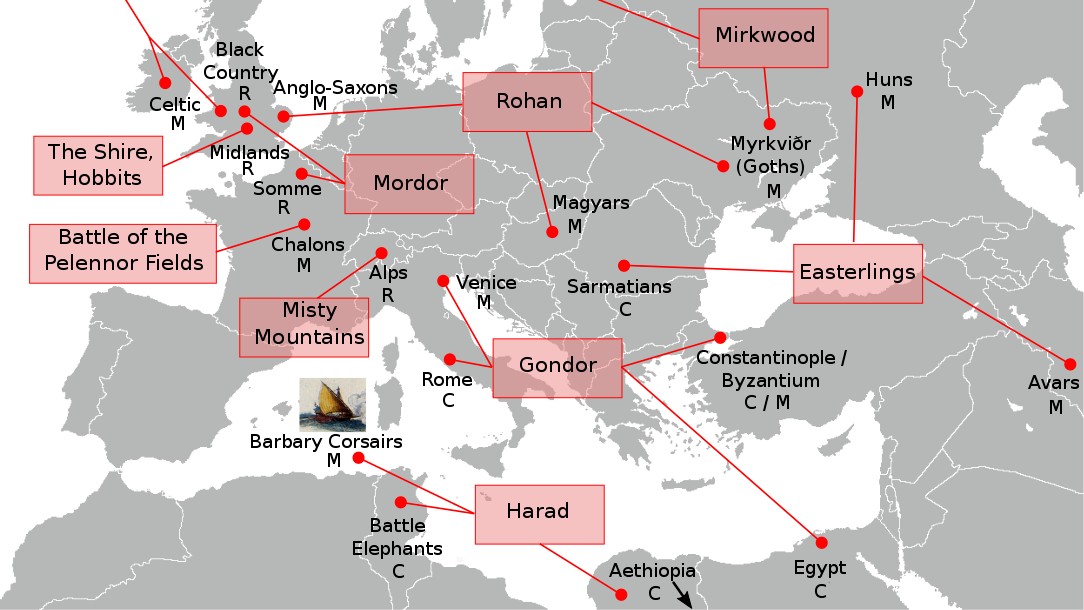

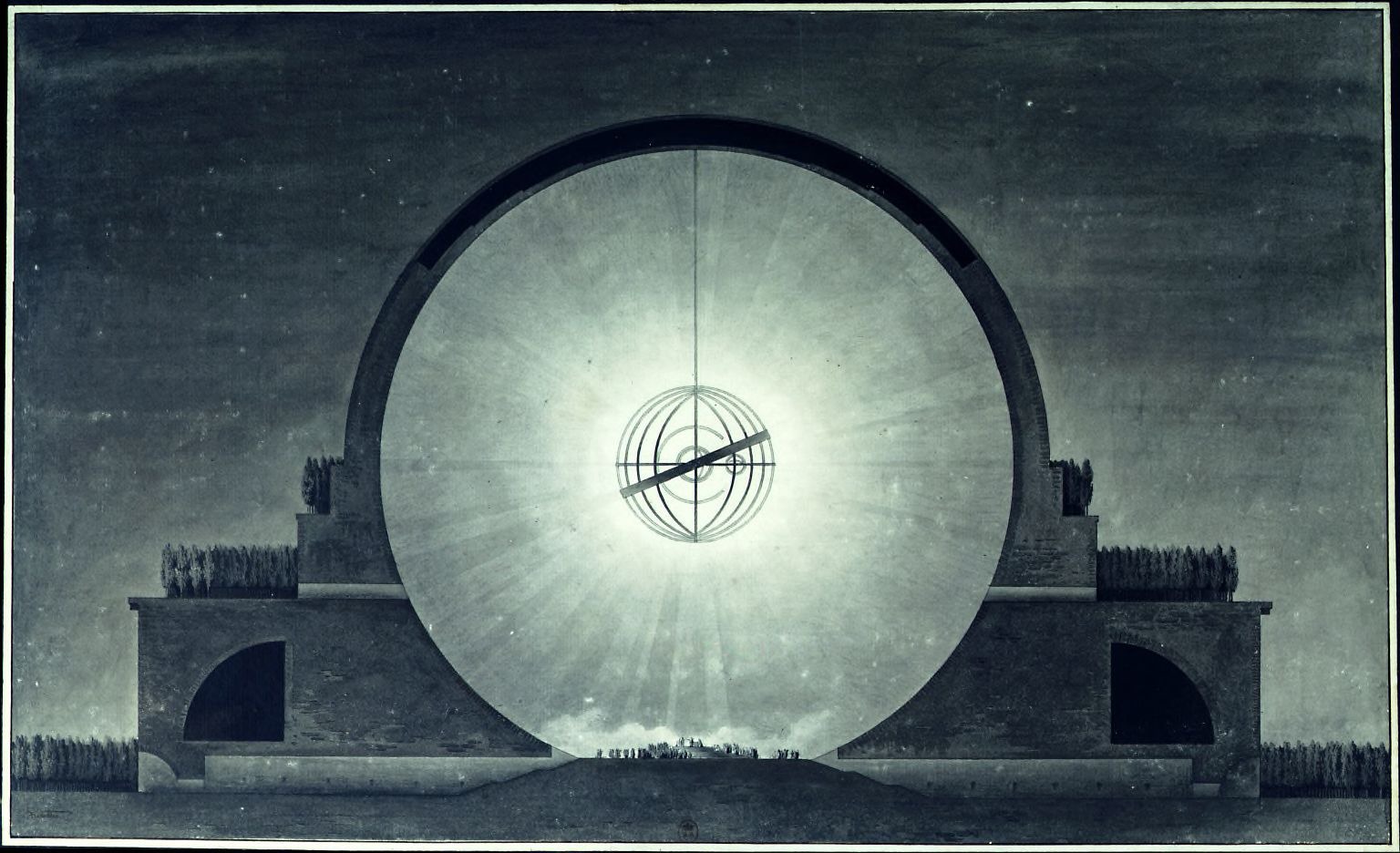

Concentric ideal-plan of a settlement (Trystan A. Edwards, 1930), and what looks like a radar installation.

Morphologie/City Metaphors is a slight volume, in paperback and black and white. Eight pages of dense theory on image and perception, symbols and analogies. Bilingual text, German and English. Followed by 50-odd image pairs, showing the mimicry between urban layouts and natural forms. It sounds like a long-shot subject for a thesis – and one almost predestined to fail. In fact, the image pairings (mostly) succeed magnificently. Perhaps also because the author knew his stuff.

City with independent satellites (Unwin, 1910), and a kitty nursing four of its young.

Oswald Mathias Ungers (1926-2007) was a German architect famous enough to be known simply as OMU. His starkly geometric work refers back to shapes and forms from classical Antiquity, reimagined in an idiosyncratic – and often controversial – manner. Ungers taught at the University of Berlin, becoming dean of its architectural faculty before moving to Cornell in 1967. He also taught at Harvard, Princeton and UCLA, but later returned to Germany.

Pentagonal ideal-city (Perret de Chamberz, 1604), and a starfish.

As an academic, Ungers defended a style his admirers labelled ‘German rationalism’; his opponents derided it as ‘Quadratism’. Ungers’ many buildings include his own house, now a listed building and the location of his archive, at Belvederestraße 60 in Cologne, the German Architecture Museum in Frankfurt-am-Main, the residence of the German ambassador in Washington DC, and an intriguing Haus ohne Eigenschaften (House without Qualities), again in Cologne.

Satellite town (de Groer, 1936), and ball bearing.

That bit of context makes it easier to understand the juxtaposition of images in the book, which at first are merely comical Aha!-moments. Ungers is using them to make a serious point about the way we perceive reality. But that’s not to say we can’t have some fun, even at the intersection of architecture and philosophy:

A map of Venice, and two hands touching.

“[T]he city-images as they are shown in this anthology are not analysed according to function and other measurable criteria – a method which is usually applied – but they are interpreted on a conceptual level demonstrating ideas, images, metaphors and analogies. The interpretations are conceived in a morphological sense, wide open to subjective speculation and transformation.”

Plan of an ideal city (Georg Rimpler, 1670), and an almost-cuddly hedgehog.

“The book shows the more transcendental aspect, the underlying perception that goes beyond the actual design. In other terms, it shows the common design principle which is similar in dissimilar conditions. There are three levels of reality exposed: the factual reality – the object; the perceptual reality – the analogy; and the conceptual reality – the idea, shown as the plan – the image – the word.”

Hilarious, isn’t it?

Ungers’ sustained analogy of city plans with other shapes is somewhat reminiscent of Raymond Queneau’s 99 variations on a very banal theme in his Exercices de style. Content-wise, the pairing of street grids with animal, vegetal and human forms recalls the zoo-morphism discussed earlier on this blog in #477 (on South Sudan’s animal-shaped city layouts), and #521 (on the Cartographic Land Octopus), among other posts.

__________

[1] Quite a few copies for sale online, don’t worry.