National Porcineographic: a Portrait of America as a Young Hog

Nothing remains of Ridge Hill Farm, once an 800-acre estate in Needham, Massachusetts. The only reminder is a street name in neighbouring Wellesley. Yet once it was the Xanadu of sewing-machine magnate W.E. Baker. And one fine summer day in July 1875, Ridge Hill Farms hosted one of the grandest parties the area is ever likely to see.

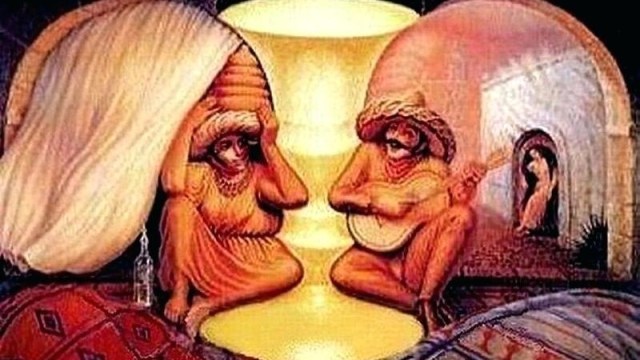

Massachusetts governor William J. Gaston and Boston mayor Samuel C. Cobb were among the many dignitaries, foreign and domestic, attending Baker’s fête champêtre, which served a double purpose: it commemorated the centennial of the Battle of Bunker Hill, fought nearby; and it was the Corner-Stone Party for a ‘Sanitary Piggery’, one that Baker believed would inaugurate a filth-free future for the entire hog-rearing industry. As the patriotic coincided with the porcine, each of the 2.500 guests received a copy of this peculiar map of the United States as a ‘good cheer souvenir’ of the event.

The map’s rather long-winded full title is: THIS PORCINEOGRAPH is copied from the Census Surveys of 1870, adding only 3 feet of territory (?) resting on Cuba, Mexico and Sandwich Islands, and the Hydro-Cephalus from Canada. Congressional Legislation is required to PERFECT this GEHOGRAPHY.

Produced by the Forbes Lithograph Manufacturing Company of Boston, this must be the world’s finest – and possibly only – example of sustained porcineography (1).

The familiar shape of America’s 48 contiguous states is shadowed by the silhouette of a trotting porker. The bristles on its back peek out over the long, straight border with Canada. Maine figures as its eastbound snout, its right eye is placed between Lakes Erie and Ontario to coincide with the Niagara Falls & Cataract (2). A giant pig’s ear covers much of Michigan and Wisconsin, in imitation of the Great Lakes.

Two legs of the continent-sized beast are coterminous with actual geographic features: its right front leg, raised, is the Florida peninsula, its right back leg, touching putative ground, is Baja California, the Mexican peninsula. An imaginary left back leg is reaching across the Pacific to step on the islands of Hawaii, or, as they were then also commonly referred to, the Sandwich Islands (bacon sandwiches, by the look of these). Its imaginary front left companion rests on a sausage-shaped Cuba (3). The state of Washington has sprouted a bristly, curly tail wrapped around Alasqueue.

The map itself is surrounded by a herd of pigs. Some are sitting in mock-allegorical poses atop it, copying the personifications of continents or countries on other maps. The main trio is labelled, left to right, Hog & Ham & Pork. Hog is holding a plate of shrimp and what appears to be a palm tree. Ham is emblazoned with a patriotic slogan (4) and holding an eagle’s nest containing a young chick and some yet to be hatched eggs. Pork is preparing a bean-based condiment by pouring brain sauce into it.

Other swine are running right around the map, each accompanied by the name, coat of arms and pork-based specialty of each American state (5). That list reads like a menu of lost regional dishes – some perhaps mercifully so. Included are such colourful recipes as:

Two small vignettes, at each of the bottom corners of the map, demonstrate the intertwined histories of government and pig-rearing in America (6). A tiny inscription shadowing the curl of the continental pig’s tail refers back to the man who commissioned this lithograph: Entered according to act of Congress by W.E. Baker 1876.

William Emerson Baker (1828-1888) may now be largely forgotten, he was something of a 19th-century Bill Gates. Baker started life as a tailor in Boston, and teamed up with sartorial colleague William Grover to found the hugely successful Grover & Baker Sewing Machine Company. Sewing machines were one of the mid-19th century’s hottest apps. The company’s fabulous success allowed Baker to retire at 40, a very wealthy man indeed.

At that time and place, wealth carried with it the moral duty (or social obligation) of philanthropy. Boston was New England’s focal point (7) for many of the era’s grand causes, be they abolitionism, suffragism or temperance (8). Baker’s do-goodery had a wide variety of outlets, including support for religious tolerance, for post-Civil War reconciliation between North and South, for the Boston Aquarium and for the fledgling Massachusetts Institute of Technology (founded in 1861). But the main thrust of his post-retirement work was in the cause of Pure Food.

Baker subscribed to the Pure Food movement’s view that unsanitary food production was the cause of much disease, and that the latter could be greatly reduced by the reform of the former. Hence his missionary work for what he called Hygienic Farming and Sanitary Cookery: “The prevention of disease among our general citizens, as well as in the army corps, is of more consequence than attention for its cure by the Medical Department.”

As one of its wealthiest patrons, Baker completely identified himself with the Pure Food cause. He turned his summer estate into a crowd-pulling amusement park with over 100 attractions. It was dubbed a ‘Fairyland of the Beautiful and Bizarre’, but Baker’s intention was as much to instruct as to amuse. The Crystal Cave (featuring Ali Baba’s Forty Thieves), the pleasure lake called Elm Tree Pond, the Norino Tower, the Floral Art Gardens, the Museum of Industry – they were all there to guide the visitors towards a more food-hygienic future.

Especially so the many saloons, restaurants and hotels dotting the estate. The guests of the 225-room, luxury Wellesley Hotel and the hiking-oriented Trephis Home Hotel were catered for by cooks graduated from the Massachusetts Institute of Cookery, one of several Pure Food institutes grouped together in the estate’s Mount Charity area. Another one was the Trepho-Phagian Institute (9), a charity providing sanitary cooking for the “invalid poor” (the hygienic quality of the food specifically aimed, one imagines, at making them less ‘invalid’).

One of Baker’s additions to the research side of Ridge Hill Farms was the aforementioned Sanitary Piggery. Baker believed that pigs were not to blame for the filth they were commonly raised in, but that this filth was the cause of much disease: “The hog is naturally more cleanly in its habits than many of those who say he isn’t (…) The flesh of those swine fed on city garbage is liable to be unfit for market, as this garbage is often fermented and sour. And thus the City of Boston, by the disposition of its garbage, directly aids… in filling our hospital wards with patients diseased from eating unwholesome pork.”

Baker’s Sanitary Piggery involved a clean environment and wholesome food for its porcine residents – it was even rumoured they had individual beds, and slept under silk sheets. That may have been hyperbole, but it underscores Baker’s belief that public health depended greatly on sanitary food production.

Baker’s ambitions exceeded his Sanitary Piggery. He wanted to establish an entire Hygienic Village, to be called Hygeria. In 1881, he petitioned the Massachusetts legislature for tax exemption, claiming that his work would benefit public health by preventing medical expenditure, thus saving the state considerable amounts of money. Hygeria would “induce the people of [Massachusetts] to practice such sanitary economies and household reforms as shall tend to diminish crime and disease and improve the vigour of the race.”

The town of Needham opposed Baker’s secessionist plans, and despite his threats to establish Hygeria in another part of the country, this refusal – not to mention Baker’s untimely death, in 1888 – doomed the project. Baker’s widow sold Ridge Hill Farms, which suffered from fire, neglect and lack of funds and was eventually sold for residential development. This map is among the few tangible relics of Baker’s Pure Food crusade.

Curiously, the area around Needham was the test site for other Pure Food experiments, such as ‘hands-free’ milking at the Walker-Gordon Laboratories, where a mechanical ‘Roto-Lactor’ provided “milk untouched by hand from cow to consumer”, at first aimed at infants, later at the general consumer. Developed in the 1930s and displayed at the NY World’s Fair in 1939, the Roto-Lactor was in operation until 1960.

Many thanks to Daphna Atias for sending in this map, found in Recipe for a Culinary Archive, an illustrated essay by American food historian Jan Longone. The Library of Congress possesses a high-resolution downloadable version, as does the Big Map Blog, mentioned earlier on this blog, whence I got the version shown here.

———–

(1) The cartographic representation of pigs, from the adjective for pigs and related animals, ‘porcine’. Other common and/or fun animal adjectives include: bovine (cows), ovine (sheep), asinine (donkeys), ursine (bears), feline (cats), galline (chickens), canine (dogs), corvine (crows), musteline (ferrets), vulpine (foxes), ranine (frogs), equine (horses), caprine (goats), pediculine (lice), and garruline (magpies). This blog treated one other example of pig-related cartography, although its non-figurative por(k)trayal of the map’s subjects may exclude it from the definition of porcineography (see #58).

(2) A clever play on the latter word’s double meaning: eye-disease, or large waterfall.

(3) The pig’s feet on Cuba, Baja and Hawaii account for the three added ‘feet’ of territory mentioned in the title. The claim on Cuba is justified by the (southern) US’s Spanish legacy, the extension towards Hawaii simply by America’s Pacific reach. The justification for the appropriation of Baja is, rather cryptically: Cast not thy (Mexican) pearls before swine least (sic) they tread them under their feet.

(4) Sic semper tyrannis: ‘Thus always to tyrants’. Attributed to Brutus, who supposedly said this when killing Caesar. Used by Americans rebelling against British rule. Adopted by Virginia as its state motto. Later also shouted by John WIlkes Booth when shooting Lincoln.

(5) Not all the entities shown here were states at this time; some were still territories, a few still had to acquire their final borders: the Dakotas were still Siamese twins, and Arizona and Wyoming were still to lose western bits of their territories to Nevada and Idaho, respectively.

(6) The left one reads: Litigation about the killing of two hogs found trespassing in a garden in Rhode Island in 1811, is said to have resulted in the election of the opposition candidate, Howell, to the United States Senate and the Declaration of War of 1812. The right one: Legislation concerning the litigation between the city crier, Capt. Kesyne, and the “widow” Sherman about a hog found astray in the streets of Boston, in 1636, resulted in the organization of the Massachusetts Senate.

(7) Not unlike Clapham was for London (see #499).

(8) A great temperance map, published earlier on this blog (see #258), was published in Boston in or around 1846.

(9) From the Greek words for ‘nourish’ and ‘eat’.

Strange Maps #511

Got a strange map? Let me know at[email protected].