When you think about the word “anxiety,” it likely comes with a negative connotation. But anxiety is a normal human emotion that nearly all of us experience. Reframing anxiety as a tool for change, adopting concepts from Zen Buddhism, and striving to live in a ‘flow state’ can quell the negative thoughts we experience and amplify your mind’s abilities.

Optimizing your brain so that you can work in harmony with your thoughts is entirely possible. These 3 experts explain how we can work with our physiology, rather than try to rebel against it.

Authors Steven Kotler and Wendy Suzuki along with psychiatrist Robert Waldinger show us how to optimize our mind, transform anxiety, and drop into ‘flow state’ for a more peaceful life.

STEVEN KOTLER: One of the really incredible things about being human is we're all built for peak performance. Flow is often described as a state of kind of effortless effort. We feel like we're propelled through the activity. Everything else just seems to disappear. You hear the word "anxiety," you think, "Oh God, this thing I wanna kick out the door. I want to get rid of it." I wanted to flip the script. Anxiety is a normal human emotion. We all have it. We can use neuroscience and tools from psychology to learn how to take advantage of anxiety. Because we tell ourselves so many stories about who we are, and who we're supposed to be. Once we realize that everything is always changing, it helps us let a lot of that go. My name is Stephen Kotler. I'm a writer and a researcher. And my latest book is "The Art of Impossible Flow Itself."

Flow is often described as a state of kind of effortless effort. We feel like we're propelled through the activity. Everything else just seems to disappear. Time is gonna dilate, which is a fancy way of saying it's gonna pass strangely five hours, go by in like five minutes. Occasionally it'll slow down. You get a freeze frame effect. I, anybody who's been in a car crash, for example, intuition tends to get turned up a lot. This is an basketball player in the zone, seeing the hoop and suddenly it's as big as a Hulu and our frown muscles tend to be paralyzed. And what that frowning is, is a sign that the brain is doing work. This is, uh, this is a constant issue. And by my, where my wife thinks I'm mad at her or somebody, and I'm like, no, no, I'm just thinking, this is just me thinking I'm in robot mode. Actually, uh, the term is coined by Gerta who uses the German word RO, which means overflowing with joy. NCHA actually wrote about flow. William James worked on the topic, but Miha sent me high as often referred to as the godfather of flow psychology. He was very interested in sort of well meaning of life. And he went around the world, talking to people about the times in their lives when they felt their best. And they performed their best everywhere. He went, people said the same thing. I mean this altered state of consciousness where every action, every decision I make seems to flow effortlessly, perfectly seamlessly from the last flow actually feels flowy. More specifically. It refers to any of those moments of rad attention and total absorption. You're so focused on the task at hand. So focused on what you're doing. Everything else just seems disappear. But one of the things that athletes talk about a lot is what they call bell voice. Often when I'm skiing and flow, I will get directions right left, do this, do that. And it's, it's very quick. You either do what the voice is telling you to do, or you tend to crash. The challenge skills balance is often called the golden rule to flow. And the idea here is pretty simple. We pay the most attention into the task at hand when the challenge of that task slightly exceeds our skillset. So to do this work and to get good at it, you have to get good at being comfortable with being uncomfortable. So you want to stretch but not snap. So there are a number of different things you can do to sort of prepare yourself and prepare the environment to drop, to flow. The flow triggers are your toolkit. 22 of them have been discovered. There are probably way, way more, but so far researchers have identified 22. The most basic of flows, triggers, complete concentration. You really want to sort of start your work session. If you can, um, in relationship to your physiology. I like to wake up at 3 34 o'clock in the morning. That's when I'm most awake, most alert. I am married to a night out. My wife doesn't wake up till 5, 6, 7, o'clock eight o'clock at night. That's when her brain comes alive. And then you want to try to block out 90 to 120 minutes for uninterrupted concentration practice, distraction management ahead of time. So you want to turn off your phone, turn off email, Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, et cetera, all your messages, all your alerts. There was a study where they found that coders and flow. They get knocked out by distraction and knock at the door, a text alert or whatever it can take. 'em 15 minutes to get back into flow. If they can get back in at all, low only shows up when all of our attention is in the right here right now, one way to kind of explore flow triggers is a cluster of them that are predominantly dopamine triggers. They drive focus. They drive attention that drive alertness, um, and, and excitement. And there's a lot of different ways to get dopamine. Novelty produces, dove mean we see the same thing with unpredictability complexity, the experience of awe. You look up at the night sky and you see stars everywhere. And you know, those stars are actually universes and you get sort of perceptual vastness. You've ever done a crossword puzzle, or Succo you get an answer that little rush pleasure you get that's dopamine. And then you usually get a couple of answers right in a row. That's because the dopamine that is now in your system is amplifying pattern recognition. We get that same dopamine from risk taking, and this could be physical risks, emotional risks, social risks, and intellectual risks, possibly spiritual risks. We get the dopamine, not as a reward for taking the risk, which is what some people, uh, used to believe. But now we know it's to kind of drive motivation. Now there are lots of different intrinsic motivators, but from a motivation standpoint, there are five and they're all designed to be built into one another and work in a sort of specific order in a specific sequence. The most base to human motivator is curiosity. One of the things we get from curiosity is focus for free. When we're curious about something, we don't have to struggle. We don't have to burn a lot of calories trying to pay attention to it. Curiosity is designed biologically again to be built into passion and think about we've all fallen in love how much attention you pay, Hey to the person you're falling in love with you. Can't stop thinking about them. Can't stop staring at them. That's a tremendous amount of focus for free. Now passion is incredibly useful, but as a motivator, you can go one better, which is purpose. Everybody wants to talk about, oh, I have a purpose and it's this big altruistic thing. And it's good for the world. And all those things may be true. But from a peak performance perspective, it's very, very selfish. Once you have purpose, the system demands autonomy. I want the freedom to pursue my purpose. And once you have that freedom, the system wants the last of the big motivators mastery mastery is the skills to pursue that purpose. Well, one of the really incredible things about being human is we're all built for peak performance flow is universal in humans, actually universal in most mammals and deaf, all social MAs. There's a shared collective version of a flow data, a a team performing at their best, a group performing at their best. This is called group flow. In fact, studies have shown that the people who score off the charts for these characteristics who score off the charts for overall wellbeing and life satisfaction, are the people with the most flow in their lives. We're all capable of so much more. Then we know that is a commonality across the boards at the largest lesson. The 30 years in studying peak performance has taught me. And the way I sort of like to think about it is motivation is what gets us into the game. Learning allows us to continue to play creativity is how we steer and flow, which is optimal. Performance is how we amplify all the results beyond all reasonable expectation.

WENDY SUZUKI: My name is Wendy Suzuki. I'm Dean of the College of Arts and Science at New York University, and my most recent book is "Good Anxiety: Harnessing the Power of the Most Misunderstood Emotion."

- Anxiety is the feeling of fear or worry typically associated with situations of uncertainty. Brain plasticity is the brain's extraordinary ability to change and rewire itself in response to the external environment. I've tried to use and explore the boundaries of brain plasticity to address some very challenging issues, particularly our high anxiety levels. You hear the word "anxiety," you think, "Oh God, this thing I wanna kick out the door. It's a disease. I have it. I don't know how to get rid of it." One of the first things that I wanted to do was flip the script on our whole mindset around anxiety. Anxiety is a normal human emotion. We all have it, okay, so you're never gonna get rid of it. It evolved to protect us, and so my whole book, "Good Anxiety," is teaching us to look at anxiety in a different way. The amygdala is a brain structure that is automatically activated when you hear that bump in the night that launches your anxiety, and the brain area that could help that calming in that situation is the prefrontal cortex, the area that's involved in executive function, that helps you order your day. But unfortunately, in situations of high stress, high anxiety, what happens is not only is your amygdala activated but your prefrontal cortex gets shut down too, so that makes the situation even worse. One thing that trips essentially all of us up is something called the 'negativity bias,' which says that we are more prone to see the negative sides of things than the positive. What happens is, if you're tired, if you're stressed, if lots of problems are coming up, you will tend to see the world in, "Oh my God, this person hates me. I'm never gonna get the job. I'm never going to lose the weight that I wanna lose." All these things become part of the big stone of anxiety dragging along with you. 'Cognitive flexibility' is the idea that we are able to look at and approach situations in lots of different ways. We are habit-forming animals, and sometimes without even knowing it you are approaching the same situation the same way that you approached it when you were six years old. Cognitive flexibility says that if there is a realization, there are other ways to approach it. You have the ability to do just that. I dove into trying to find gifts from all the different kinds of anxiety, and that's how I came up with the six gifts or superpowers of anxiety. Let me mention my top three: The first one is the superpower of productivity, that "what if? list." What if you didn't do that, or what if you did that and you didn't do it right? That anxiety is focused on things that are important to you in life. That is the key. Evolutionarily, anxiety evolved to have us put an action on it. 2.5 million years ago, it was either you fight the danger that was causing anxiety or you run away from it. That is the fight or flight response. The way to transform it is to turn that what if list into a to-do list. Put an action on each one of them, whether it's asking a friend for help, doing something, Googling something, and go tick through them one by one. Superpower number two is the superpower of flow. Flow is a psychological state. It's those moments that you're doing something that you're really good at. Times stands still. It's like you're moving in slow motion and everything is just going beautifully. All the data out there says that anxiety can eliminate flow. I know I wanted to talk about flow, but I couldn't just say, "Well, sorry, if you have anxiety, no flow for you." Okay, maybe it's not classic flow. Maybe it's "micro flow." Your own anxiety can make your own moments of micro flow which we all have during the day, even if you don't realize you do, be even flowier. Superpower number three. Think about that anxiety that is most familiar to you, your most common form of anxiety. You know what it feels like. You know what it looks like. All you have to do is notice when others might be suffering from that same form of anxiety, and here's your superpower. All you have to do is give a kind word, a simple helping hand in that situation, and I love this superpower because I can't think of anything that we need more in the world today than higher levels of empathy. An 'activist mindset' is one that is flexible, that can look at a situation and see lots of different possibilities, everything from that negativity bias all the way to, "Oh, actually, maybe this is gonna teach me something really interesting, really new." To have an activist mindset requires cognitive flexibility. You're gonna try something new. Sometimes it's hard, but if you practice it in different ways every single day it can be something that becomes a very powerful tool. This is a really important part of my book, and I think it was emphasized because of this situation that really shaped the book, which is a difficult passing of two of my family members, and really coming out of that with a beautiful example of an activist mindset. Everybody's going to experience loss of a loved one during their lifetime. My activist mindset was knowing that all of that pain and that loss and that sadness was undergirded by love for these people, and that was my activist mindset. I brought that beautiful, helpful, almost life-saving example of activist mindset to my addressing anxiety. What is it about my anxiety that is difficult? Can I bring a superpower or a gift from that as an opportunity to learn, to grow, and to learn more about yourself?

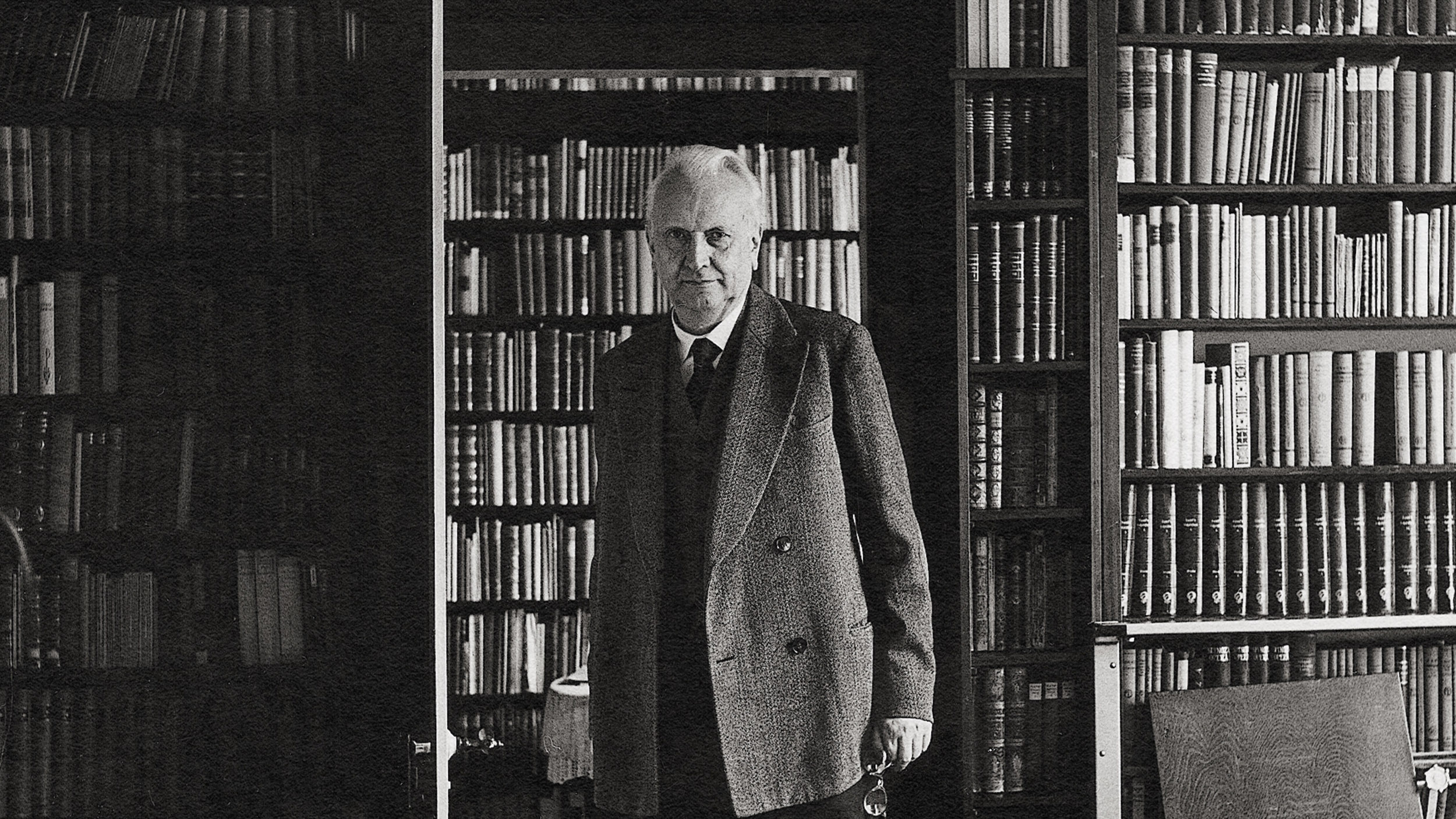

ROBERT WALDINGER: I'm Robert Waldinger. I am a psychiatrist and I'm professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School. I direct the Harvard Study of Adult Development at Massachusetts General Hospital.

- Zen emphasizes community. It's called 'Sangha' in the Buddhist language. and it's really the idea that we practice learning about ourselves and each other by being in relationships with each other, both during meditation sessions and out there in the world. I am a Zen practitioner. I'm actually a Rōshi, a Zen Master. It's a big part of my life, and it is an enormous benefit in terms of how I think about my own life, other people's lives, how I think about my research, and how I think about working with patients. I would rate the concept of impermanence as, number one, as the greatest hit of Zen Buddhism. Basically, the idea of everything constantly changing There's nothing to hold onto in the deepest sense. And that on the one hand, that can be scary, on the other hand, it can be an enormous relief because we tell ourselves so many stories about who we are, and who we're supposed to be, and how the world is supposed to be, and when we really know the truth of impermanence, we let a lot of that go. Once we realize that everything is always changing, it helps us be more compassionate to other people 'cause we realize that they are also dealing with all the complexities of a self and a world that's constantly changing. The Four Noble Truths are perhaps the most iconic teachings of the Buddha. They start with the Buddhist statement Now, it's often said that, "The Buddha was teaching that you could get to a point where you never suffer anymore." Zen does not teach that. Rather, what we can do is learn to be with what's unsatisfactory in life, learn to be with unhappiness, even be with pain in a way that makes it more bearable, in a way that doesn't layer on The optional suffering being the stories we tell about how unfair it all is, for example, that I have back pain or how unfair it is that I've got a cold today- that all of these things are workable. It makes me a little less likely to blame other people for what's going on in me, and that can be hugely helpful. When we talk about harmony in relationships. The best definition I know of mindfulness is simple: So right now, for me, that's talking with you. That's the feel of the chair on my back. It's the feel of the air on my skin. You can work on your mindfulness right this moment, by simply paying attention to whatever stimuli are reaching you. It might be your heartbeat, it might be your breath, it might be the sound of the fan in the room-anything. And simply letting yourself be open and receive whatever is here right now. And you can do that in any moment. Buddhism talks about the idea of attachment. It's really about holding on tightly to a fixed view of something. Zen teaches that unsatisfactoriness is always there in life, and that we do have preferences, but that what we can do In other words, to insist less that the world be a certain way. I mean, think about in relationships, how much we try to insist that someone else be a certain way that we want them to be, and how much less we suffer if we let that go. And just assume that that person is allowed to show up in the world as they are, and we are allowed to show up in the world as we are. So this idea of relieving suffering is in Zen, the idea of being able to face towards suffering, looking at it, and living with it in a way that hurts less. There's a concept of Metta, loving-kindness, in Buddhism, and there are a couple of different ways that it's talked about. One is an explicit skill that we can cultivate. You can do a loving-kindness meditation where you think about another person and you say to yourself, "May you be happy. may you be at peace." And you do that over and over again, and you come to feel differently about the other person, including about people you don't like very much, or you're angry at. So there's that way of actively cultivating a skill. There's another way, which is simply by becoming more and more aware of your own pain, your own anxious, angry thoughts, your own difficulties. Because what happens when we become more aware of that through meditation, for example, is that we become much more empathic toward other people. And naturally, that kind of loving kindness arises, where we see an angry person and say, "Oh, I wonder if that person is having a terrible day," rather than immediately reacting with our own anger. And so that's a different way to cultivate loving-kindness, but it happens pretty reliably through meditation. And finally, there's a wonderful teaching in Zen about Beginner's Mind. The idea that we let go of all the stories we tell ourselves that we're so sure of. Having a beginner's mind really helps in relationships because it allows us to be curious, it allows us to say, "Okay, there's so much I don't know about this person, let me watch closely. Let me notice what I haven't seen before about this person. Let me find new ways to interact with this person." And that brings a kind of freshness and openness to relationships that can otherwise, easily get stale. Shunryu Suzuki was a Zen Master who had a saying that I love. And what he meant by that is when we can remain open to many possibilities, rather than being so sure that we know what's what, that we become open to surprise, open to new ways of experiencing ourselves and the world, that make us suffer a great deal less than when we are so-called experts. And the older I get, and the more people call me an expert, the more aware I am of how little I know.