What do Aretha Franklin, Bruce Springsteen, Bob Dylan, and Stevie Ray Vaughan have in common? In addition to being phenomenal 20th-century musicians, all were scouted or had their careers furthered by the American record producer John Hammond.

Finding talent is a talent in itself. And to the author and economics professor Tyler Cowen, it is a talent that gets neglected in many companies, whether due to biases, boring hiring practices, or a failure to think outside the box.

As Cowen explains in this Big Think video, the way to go about finding exceptional talent is by searching the areas where the rest of the market is not looking.

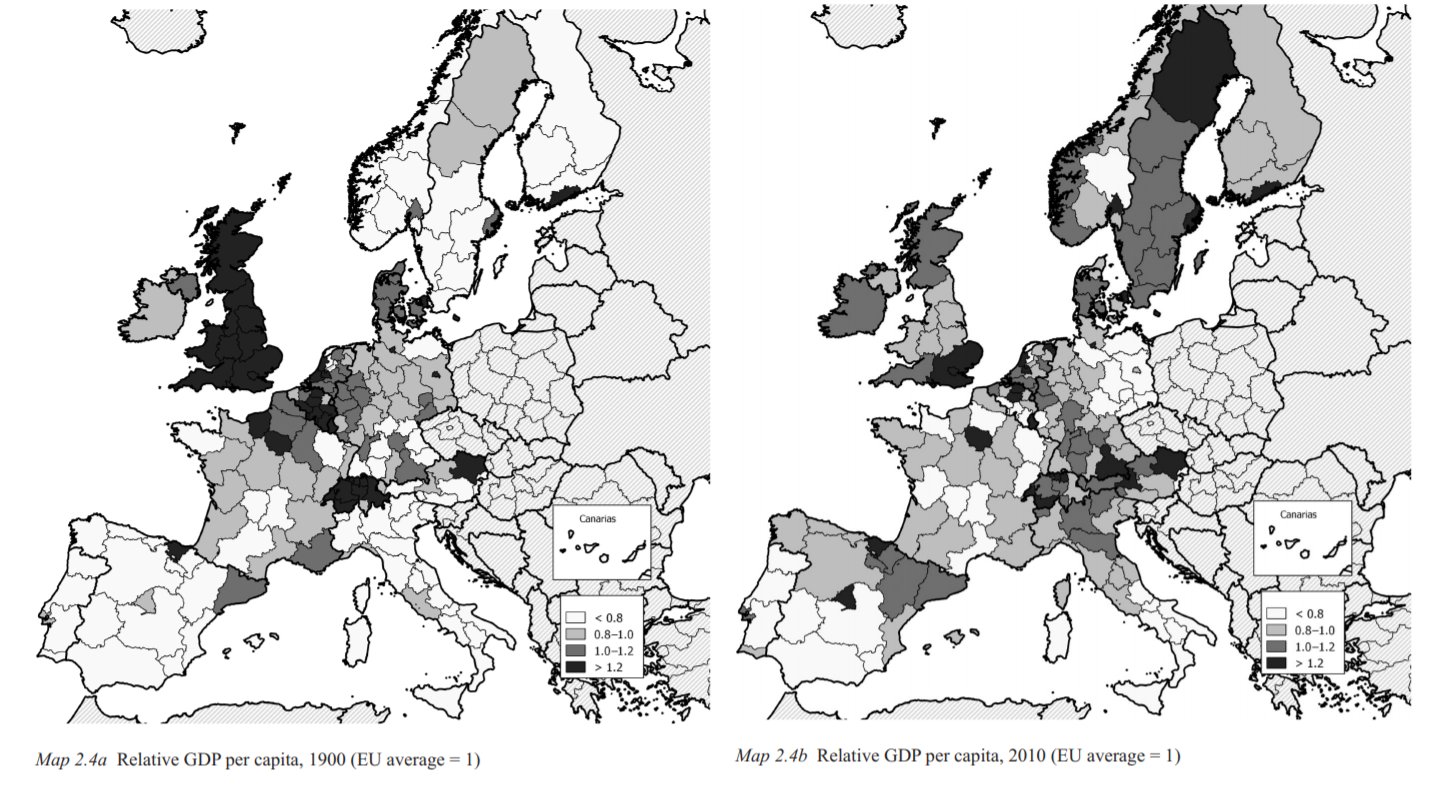

TYLER COWEN: My entire life, I've been involved with starting or managing projects. And in virtually every case, I found the true binding constraint was not enough talent. There was a recent study that estimated the total value of talent, or human capital, in the world, is over $550 trillion. So it seemed to me that as a social problem, we're not taking talent seriously enough. We end up with a lack of opportunity, excess inequality, and many individuals simply not performing up to their maximum potential.

I'm Tyler Cowen. I'm a professor of economics at George Mason University. My latest book, co-authored with Daniel Gross, is called "Talent: How to Identify Energizers, Creators, and Winners Around the World."

John Hammond was one of the great musical talents of the 20th century. But his contribution was not singing or playing an instrument. What he did was to find other musical talents. So he found and identified Count Basie, Aretha Franklin, Benny Goodman, Bruce Springsteen, Bob Dylan, Stevie Ray Vaughan. He was one of the most phenomenal talent scouts of the 20th century. He had at least two key features in his search for musical talent. First, his primary motive was love for music. He wasn't necessarily out to make as much money from these people as possible. Second, he did not have preconceptions about race or gender. And he, you could say almost ruthlessly, was devoted to hearing quality and then seeing through the process of advancing those people in their careers. What I'm saying in my book with Daniel Gross is that we need more John Hammonds, but in every single walk of life.

There are so many problems on how talent evaluation is done today. In larger corporations, the problem tends to be too much bureaucratization. Too many boring interview processes that just make everyone a little bit numb. The interviewer goes through some rehearsed questions. The interviewee goes through some rehearsed answers. Everyone knows it's a bit phony. Neither side really learns that much. But I think that's also just the beginning of the mistakes we're making. One problem is that people, when hiring, they're too prone to hire other people like themselves. Those are virtues they find relatively easy to detect. Think about the role of intelligence in the hiring process. For people who are highly intelligent, highly skilled, the evidence is that they are overrating intelligence. For any kind of job, there might be some basic, minimum level of intelligence that would be required. But when you look above that level, it's remarkable how weak is the correlation between success and intelligence. There are other factors such as drive and determination, energy levels, how well you work with other people, leadership skills, charisma- all of those can be more important than intelligence. So I wouldn't say that everyone overrates intelligence, but it's the smart people who do, and that's exactly the problem.

If you're hiring people, you're also looking for people who are undervalued by the rest of the market. The way you really do well is by finding undervalued talents where the rest of the market is not seeing something. It could be the market doesn't understand fully how talent works. It could be a case of prejudice. There can be issues across race. There can be qualities that might appear negative, like neuroticism, but actually for a lot of jobs, neuroticism is a good thing. For your own success, focus not only on talent at the absolute level, but focus on which talents are the truly undervalued ones. I think another area where you find major biases is gender in the workplace. For instance, there is good evidence that very smart men tend to underrate how smart the very smartest women are. In most cases, I don't think it's explicit prejudice or chauvinism, though there is some of that. Men, when they interview women, at least on average, they tend to put too much weight on how they perceive the woman's personality. Whether they individually find it pleasant or agreeable. That might matter for the job, but you know, very, very often it doesn't. I think by being more open and just trying to look past some of your immediate emotional reactions, you can make better decisions.

Disability is a very important topic in the workplace today. But let me first say, I don't even like the word "disability." What is called a disability is not in every case a disability, or it can be understood in some better and more complex way. There are large numbers of individuals who are, for whatever reasons, quite different. One of the most common reasons might be ADHD. Another possibility would be some form of autism. These individuals do not always interview well, and very commonly they didn't do well in school 'cause our school systems, they are not well-designed to deal with neurodiversity. But don't be so quick to dismiss them on the grounds of a bad interview or bad grades. Some of our greatest talents are highly unusual. There's plenty of talent there that is currently greatly undervalued.

Of all the different parts of the American, and indeed global economy, I think the sector that does the best at finding talent is venture capital. Because the way venture capital is structured a lot of your investments, they're gonna lose money- you know it. But there'll be a small number that return to you 100x or 200x your initial investment. So your emphasis is on the deals you might be missing and how you can find them. And that makes people more open-minded, more tolerant of their own errors, less risk-averse, and more willing to think outside the box. They have the mentality: "Fear of missing out," and that's the direction we all need to move in.