When a customer, an employee, or a senior leader has set their sights on a certain course of action and then runs into obstacles that make it slower, harder, more frustrating, we call this Organizational Friction. Many times, that can be a bad thing, but best-selling author and organizational psychologist Bob Sutton argues that we can actually harness it to benefit us.

One thing that Sutton emphasizes in his book The Friction Project is that you should first ask yourself if your course of action is the ‘right’ or ‘wrong’ thing to do. If it’s the right thing to do, it should happen fast and be relatively frictionless. The ‘wrong’ thing to do is often full of friction, but the right thing, although it may have some ‘constructive friction,’ is often able to push forward and make progress without harsh obstacles.

Here are 2 easy tricks to solve any problem and make friction your secret weapon.

BOB SUTTON: When we face a problem, whether it's planning a trip, fixing a Lego model, or leading an organization, our natural tendency is to sort of race ahead. But some friction, well, that's actually a good thing. I think a good analogy here is the analogy of a race car. The teams that win, they don't go pedal to the metal the whole time. They break when they go in the corners. They pull in for pit stops. And when the car is on fire, they pull over, stop, and get out so they don't die.

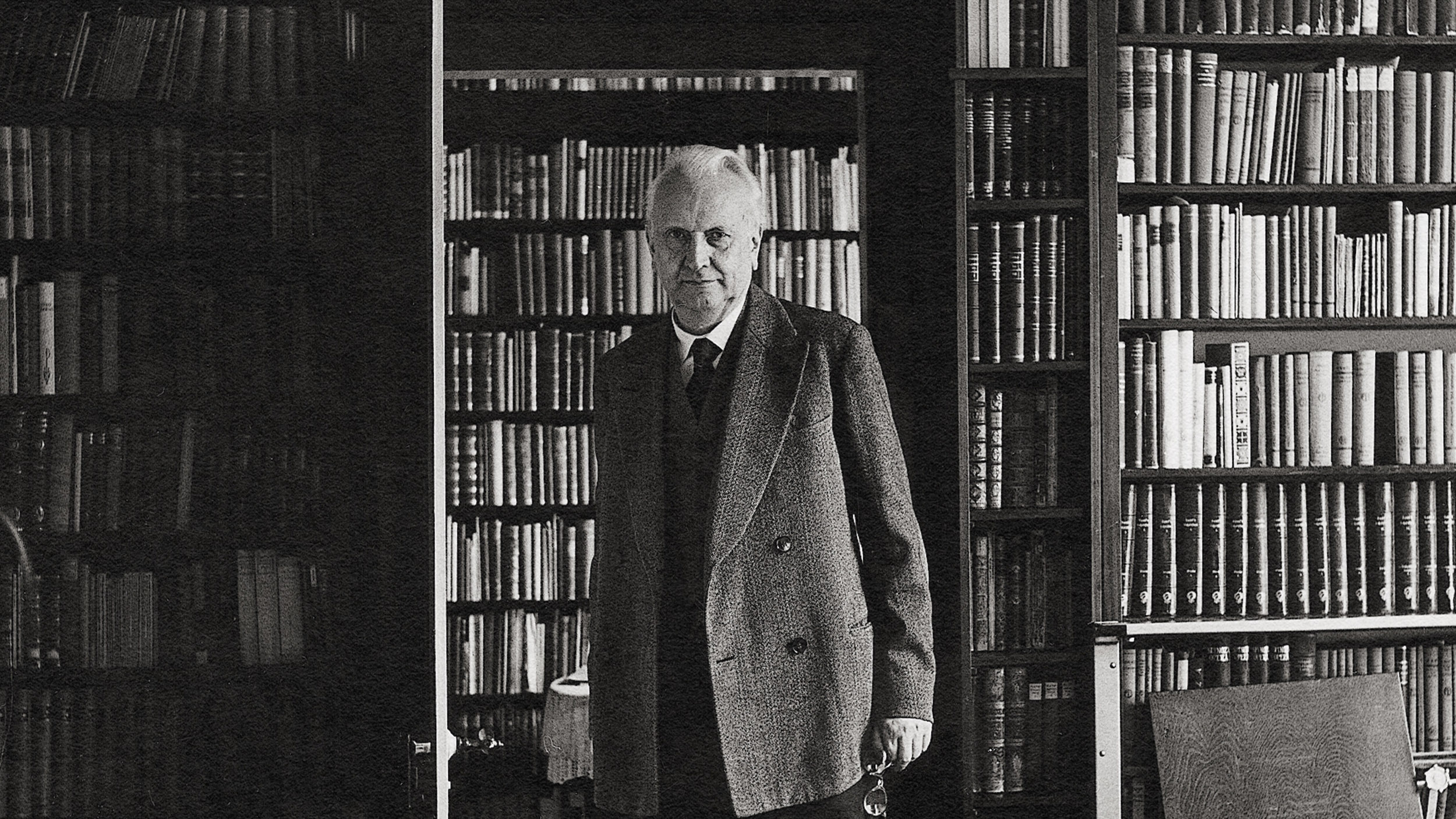

So a customer, an employee, a senior leader, when they want to do something and they run into obstacles that make it slower, harder, more frustrating. We call this organizational friction. And a lot of times, that's a bad thing, but sometimes that's a good thing. I'm Bob Sutton. I'm an organizational psychologist and best-selling author of eight books, including, "The Friction Project: How Smart Leaders Make the Right Things Easier and the Wrong Things Harder."

One thing that we emphasize in our research and in the book, "The Friction Project," is: Is it the right or wrong thing to do? And it's ridiculously simple, which is that if it's the right thing to do, I don't know, paying a bill, getting reimbursed for a travel expense, then it's the right thing to do. It should be easy, and it should happen fast and be frictionless. But if it's the wrong thing to do, I don't know, stealing money from your organization, breaking a law, well, those things, they should be difficult or impossible to do.

So a good example of constructive friction is Elizabeth Holmes, then CEO of Theranos. She did some unlawful things trying to sell a blood testing device that didn't work, and she started pressing military officials to put her blood testing device on military helicopters. And in fact, she even had a four star general press the sort of lower-level lieutenant colonel bureaucrats to put this on helicopters, and they refused because it did not have FDA approval. And there's this rule that it had to have FDA approval, which, well, that's actually a good thing.

And an interesting contrasting example to Elizabeth Holmes is a company in San Francisco called Sequel, which has reinvented the modern tampon. They went through all the friction to develop the product over and over again, to get FDA approval, and now it's being manufactured and sold. And to me, that's a good example of constructive friction. They took the slow, hard road, and now they have a legitimate product that we know works. In the name of full disclosure, I just invested twenty-five thousand dollars in their company. I may or may not get it back, but I couldn't resist. Anyway.

A friction fixer is someone who is obsessed and focused on making the right things easier and the wrong things harder, and they see themselves as trustees of others' time. They're constantly aware of how the big and little decisions they make waste people's time, maybe are a good use of people's time. And a good example of this, I took a visit to the Department of Motor Vehicles office. So I get there at 7:30 in the morning. There's a long line. There's sixty people in front of me. It's like, I know what I'm going to be doing all day. But at 7:45, this wonderful gentleman walks out, asks each of us why we're there. Some people he sends away because you can't get a passport at the California DMV. Others of us like me, he gave a form to fill out, told us what line to get in, and I expected I would spend three hours going through the process. I was out of the office at 8:20 in a state of shock that a visit to the Department of Motor Vehicles was one of the lowest friction experiences I've had, and it was in large part because of that gentleman who went down the line, showed respect for our time, and helped us navigate quickly through the process.

And, yes, just because you aren't at the top of the pecking order doesn't excuse you from being a trustee of others' time. One of the things that we think that good friction fixers do is they're skilled at diagnosing what ought to be hard and what ought to be easy. And there's two questions that great friction fixers ask. The first one: Do I know what the heck I'm doing? In many situations, it's great to think fast and be on automatic pilot. But when we're in a cognitive mind field, when things are falling apart, maybe you should sort of stop yourself and just do nothing.

A good example of this is Google Glass, which was a computer meets your eyeglasses. And Sergey Brin, co-founder, saw the product, fell in love with it, and he kind of ripped it out of the hands of the team, even though they were telling him it wasn't ready for prime time, manufactured thousands of them, gave them to a bunch of famous people, but it had battery life problems, security problems. It didn't work. People couldn't figure out how to operate it, and it was actually on the list of the worst products of all time. So sometimes, even if you're the boss, you need to slow down and think before you make a dumb decision. So that's the first one.

The second diagnostic question is whether or not the decision is reversible. Firing the CEO, acquiring a company, selling your company. If you're going to make a decision like that, you got to kinda slow down and not screw it up. But if you're doing something that's reversible, then in that situation, you should sort of throw it out in the world and see what happens. I'll tell you a little story. There's a famous firm called IDEO, and it used to be fifty people, and it was great. They'd have everybody together. It would feel like a community. They grew to a hundred and fifty people. There was confusion. They had a hard time staffing projects. And so the CEO and founder, David Kelly, called the whole company together. But right before this meeting, he shaved off his Groucho Marx type mustache, and none of us had ever seen him without his mustache, including his wife who screamed. And he looked at everybody in the room and he said, "Okay, we're going to do a reorganization. This change is just like my mustache. It's a reversible prototype. We can change the structure just as I can regrow back my mustache." Now if he cut off his finger, that would not be a reversible prototype. So you've got to be careful that some prototypes and some changes are one-way doors that there's no going back.