DNA analysis may have finally revealed what killed 15 million Aztecs

Credit: Rischgitz / Getty Images

- When Europeans arrived in North America, they brought pathogens that natives were not immune to.

- Smallpox wiped out 5-8 million Aztecs shortly after the Spanish arrived in Mexico in 1519.

- But a different disease entirely is now suspected to have killed 15 million Aztecs, ending their society.

When Europeans arrived in North America, they carried with them pathogens against which the continent’s native people had no immunity. And the effects could be devastating. Never was this more true than when smallpox wiped out 5-8 million Aztecs shortly after the Spanish arrived in Mexico around 1519. Even worse was a disease the locals called “huey cocoliztli” (or “great pestilence” in Aztec) that killed somewhere from 5 to 15 million people between 1545 and 1550. For 500 years, the cause of this epidemic has puzzled scientists. Now an exhaustive genetic study published in Nature Ecology and Evolution has identified the likely culprit: a lethal form of salmonella, Salmonella enterica, subspecies enterica serovar Paratyphi C. (The remaining Aztecs succumbed to a second smallpox outbreak beginning in 1576.)

Cocoliztli was therefore probably enteric fever, a horrible disease characterized by high fever, headaches, and bleeding from the nose, eyes, and mouth, and death in a matter of days once the symptoms appeared. Typhoid is an example of one enteric fever. “The cause of this epidemic has been debated for over a century by historians, and now we are able to provide direct evidence through the use of ancient DNA to contribute to a longstanding historical question,” co-author Åshild Vågene of the Max Planck Institute in Germany tells AFP. (S. enterica no longer poses a serious health problem to the local population.)

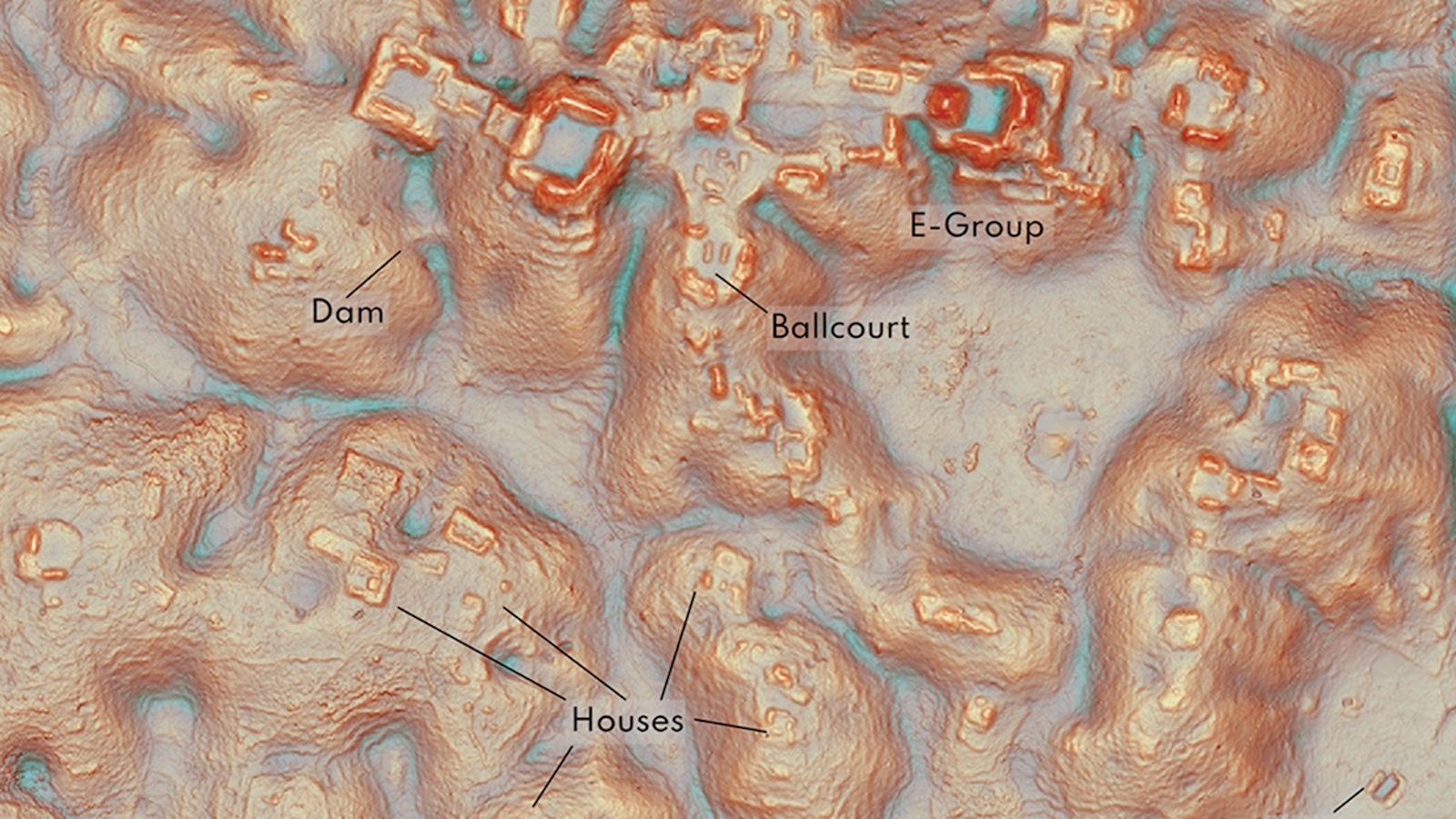

The study is based on DNA analysis of teeth extracted from the remains of 24 Aztecs interred in a recently discovered cemetery in the Mixteca Alta region of Oaxaca, Mexico. The epidemic grave was found in the Grand Plaza of the Teposcolula-Yucundaa site.

The study’s search for known pathogens was extensive. Study co-author Alexander Herbig says, “One of the most important aspects is we didn’t need to make any assumptions.” The team used a DNA-sequencing program called MALT to analyze the teeth. “We tested for all bacterial pathogens and DNA viruses for which genomic data is available,” says Herbig. Teeth from 10 of the bodies had traces of salmonella.

Researchers suspect the Spanish brought the disease in tainted food or livestock because the teeth from five people who died prior to the Europeans’ arrival show no trace of it—this is not a huge sample, of course, so it’s difficult to be certain. Another team member, Kirsten Bos says, “We cannot say with certainty that S. enterica was the cause of the cocoliztli epidemic,” adding, “We do believe that it should be considered a strong candidate.”

A chilling consideration is that the same strain of bacteria has been identified in a Norwegian female who died in 1200, 300 years before it appeared in the Aztec community. Clearly, Europeans weren’t as defenseless against it as those in the Western Hemisphere.

It’s entirely possible that some other unknown pathogen was the true bacterial cause of huey cocoliztli, or that S. enterica was somehow already present in the areas of Mexico and Guatemala where the epidemic occurred. Still, the study’s evidence is compelling. As more cocoliztli grave sites are discovered, further DNA analysis will no doubt be undertaken.