Is Your Vote Safe? The Hazards of Computerized Voting

Hurricane Sandy has introduced significant uncertainty into next Tuesday’s presidential election. But even without a natural disaster hobbling transportation and cutting off power to as many as 10 million people on the eastern seaboard, we all have reason to wonder about the safety and accuracy of our votes — and to worry that the process may be ideologically tilted out of view of the general public.

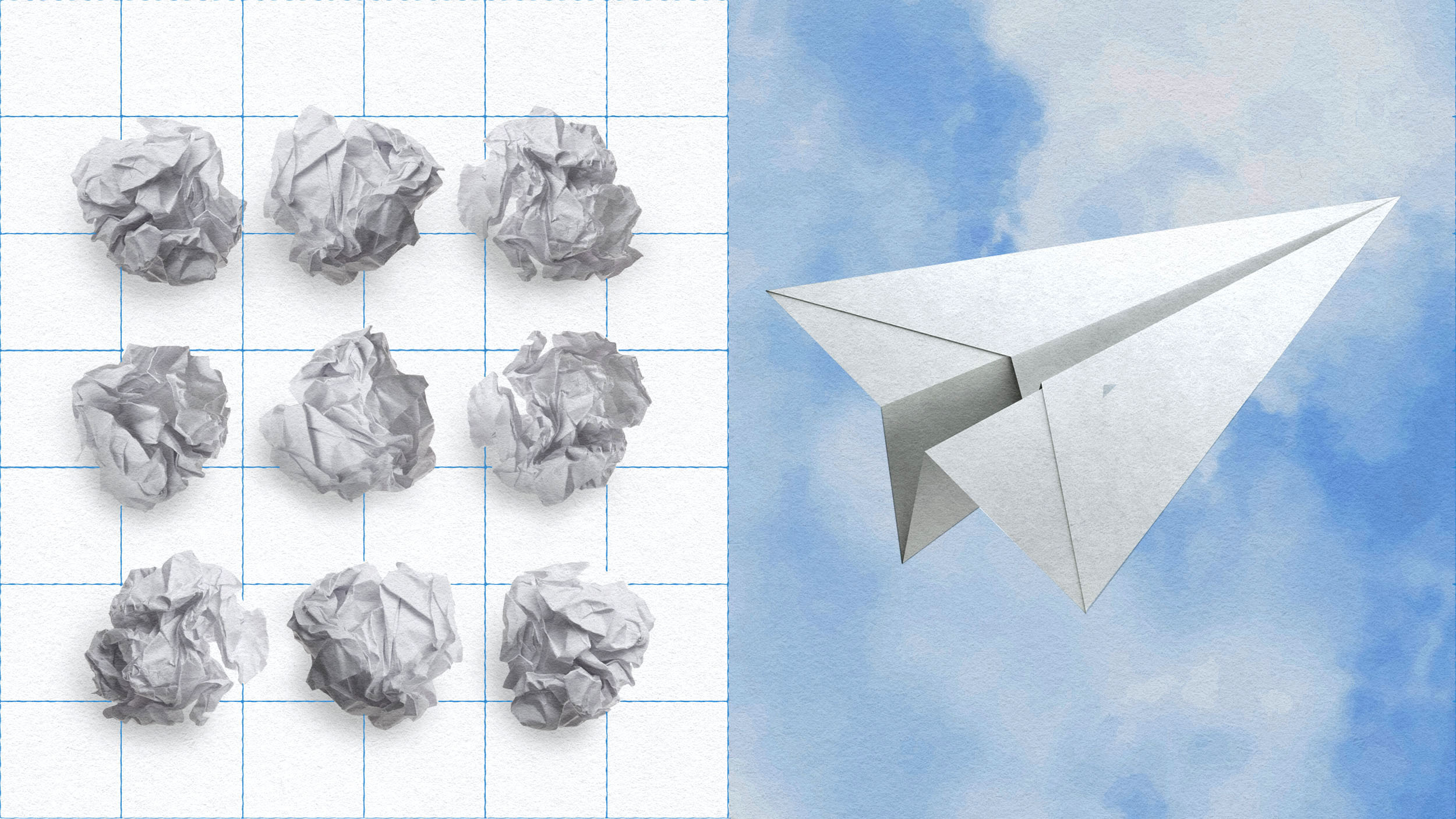

As frustrating as the “hanging chad” incident in Florida was in 2000, at least there were chads to inspect, and we could watch the whole process unfold on television. But with the advent of Direct Recording Electronic (DRE) voting, which will be the medium by which 35 percent of Americans vote next week, in most cases there are no physical ballots to review at all. With electronic voting, there is no paper trail.

Early in her important article in this month’s Harper’s, “How to Rig an Election: the G.O.P. Aims to Paint the Country Red,” Victoria Collier sets the stage:

We are now in the midst of yet another election season. And as November 6 approaches, only one thing is certain: American voters will have no ability to know with certainty who wins any given race, from dogcatcher to president. Nor will we know the true results of ballot initiatives and referenda affecting some of the most vital issues of our day, including fracking, abortion, gay marriage, GMO-food labeling, and electoral reform itself. Our faith-based elections are the result of a new Dark Age in American democracy, brought on, paradoxically, by technological progress.

These are strong claims, and Collier devotes over 7000 words to substantiating them. The argument breaks down into two distinct contentions: (1) In the age of electronic voting, “we have actually lost the ability to verify election results” and (2) The “statistically anomalous shifting of votes to the conservative right” — the so-called “red shift” observable in elections since 1988, even those in which Democrats prevailed — can be explained by “secretive corporations with interlocking ownership [and] strong partisan ties to the far right.”

At the end of her article, Collier asks why liberals haven’t made more of the issue. Ironically, those “on the left seem most reluctant of anyone to grapple with the concept of large-scale election tampering.” Collier cites NYU professor Mark Crispin Miller, who has exposed “a wide assortment of G.O.P. vote-stealing tricks in every major election from 2000 to 2006.” No one in the media seems to have picked up his story.

“ ‘I know Michael Moore, Noam Chomsky, Rachel Maddow,’ Miller says. ‘I’ve tried for years to get them to concede that possibility, but they won’t do even that. There’s clearly a profound unease at work. They just can’t go there.’ “

Collier avers that “fear of being branded a conspiracy theorist inhibits many” from broaching the issue. That could be. As persuasive as the argument is for right-wing vote rigging — claim (2) above — the case is almost entirely circumstantial. It has the flavor of the argument for Intelligent Design as an alternative to Darwinian evolution: Just look at this organism or organelle! It works amazingly well! How in the world could the bacterial flagellum or the human eye be the result of a series random mutations selected for over millions of years? There is evidence of design here, so there must be a designer!

Likewise, Collier points to many electoral examples of discrepancies between polls and election results. How in the world could these discrepancies be explained if nobody tampered with the votes?There is an appearance of fraud here, so someone must be fixing the elections! Granted, the conclusion is often tempting. Consider Collier’s example of Georgia Senator Max Cleland’s unexpected defeat in 2002:

Early polls had given the highly popular Cleland a solid lead over his Republican opponent, Saxby Chambliss, a favorite of the Christian right, the NRA, and George W. Bush (who made several campaign appearances on his behalf). As Election Day drew near, the contest narrowed. Chambliss, who had avoided military service, ran attack ads denouncing Cleland — a Silver Star recipient who lost three limbs in Vietnam — as a traitor for voting against the creation of the Department of Homeland Security. Two days before the election, a Zogby poll gave Chambliss a one-point lead among likely voters, while the Atlanta Journal-Constitution reported that Cleland maintained a three-point advantage with the same group.

Cleland lost by seven points. In his 2009 autobiography, he accused computerized voting machines of being “ripe for fraud.” Patched for fraud might have been more apt. In the month leading up to the election, Diebold employees, led by Bob Urosevich, applied a mysterious, uncertified software patch to 5,000 voting machines that Georgia had purchased in May.

This Georgia election may have been crooked. Lou Harris may be right that the 2004 election in Ohio was “as dirty an election as America has ever seen.” The 2008 election may “suggest extensive red-shift rigging.” But no direct evidence exists to prove any of these charges. Nebraska Senator Chuck Hagel’s suspiciously large win over Ben Nelson in 1996 when Hagel had only recently resigned as chairman of Election System & Software — the company that counted the votes — justifiably furrowed observers’ brows. But as Collier admits, “whether Hagel’s relationship to ES&S ensured his victory is open to speculation.”

This is the most worrisome angle of the story: the epistemological conundrum. Argument (1) ironically casts doubt on argument (2): without paper ballots and without a functional, reliable means for independent observers to verify election results, there is no way to know if and when our votes are being switched or stolen.

Follow Steven Mazie on Twitter: @stevenmazie