Why doesn’t the U.S. win wars anymore?

Credit: UX Gun via Unsplash

- The type of wars that Americans win — major wars between the great powers — no longer occur.

- The type of wars that Americans lose — civil wars in foreign countries — are the ones that remain.

- American strength will continue to lure presidents into foreign intervention.

The following is an excerpt from The Right Way to Lose a War: America in an Age of Unwinnable Conflicts. It is reprinted with permission of the author.

We live in an age of power, peace, and loss. Since 1945, the United States has emerged as the unsurpassed superpower, relations between countries have been unusually stable, and the American experience of conflict has been a tale of frustration and defeat.

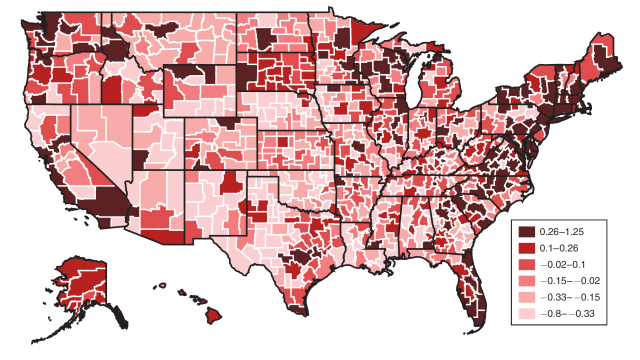

This raises the first paradox: We lose because the world is peaceful. The decline of interstate war and the relative harmony among the great powers is cause for celebration. But the interstate wars that disappeared are the kind of wars that we win. And the civil wars that remain are the kind of wars that we lose. As the tide of conflict recedes, we’re left with the toughest and most unyielding internal struggles.

It’s also hard to win great victories in an era of peace. During the golden age, the United States faced trials of national survival, like the Civil War and World War II. The potential benefits were so momentous that Washington could overthrow the enemy at almost any cost in American blood and treasure and still claim the win. But in wars since 1945, the threats are diminished. Since the prize on offer is less valuable, the acceptable price we will pay in lives and money is also dramatically reduced. To achieve victory, the campaign must be quick and decisive — with little margin for error. Without grave peril, it’s tough to enter the pantheon of martial valor.

There’s a second paradox: We lose because we’re strong. U.S. power encouraged Americans to follow the sound of battle into distant lands. But the United States became more interventionist just as the conflict environment shifted in ways that blunted America’s military edge. As a result, Washington was no longer able to translate power into victory. If America was weaker, its military record might actually be more favorable. With fewer capabilities, the idea of invading Iraq would have stayed in the realm of dreams.

Indeed, the two paradoxes are connected. American power helped usher in the age of interstate peace, as Washington constructed a fairly democratic and stable “free world” in the Western Hemisphere, Western Europe, and East Asia, fashioned institutions like the United Nations, and oversaw a globalized trading system. But this left intractable civil wars as the prevailing kind of conflict. And American power also tempted Washington to search for monsters to destroy in far-flung locations. In other words, power and peace are the parents of loss.

No one wants to go back to the days of weakness, war, and winning. A favorable record in major conflict is poor compensation for global catastrophe. But as we enjoy the fruits of power and peace, we should steel ourselves for more battlefield setbacks. The dark age of American warfare looks set to endure. In the future, conflict will likely remain dominated by civil wars. American strength will continue to lure presidents into foreign intervention. The U.S. military will resist preparing for counterinsurgency. Guerrillas, by contrast, will learn and adapt — and bloody the United States.