How our definition of freedom has changed

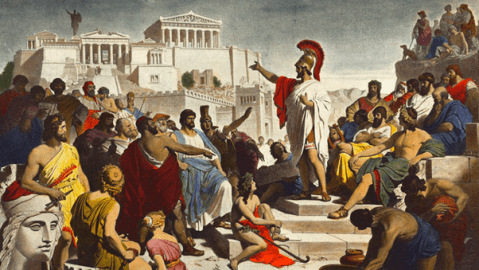

Pericles' Funeral Oration (Philipp von Foltz)

- Philosopher Ben Constant explains how democracy today is nothing like what it used to be.

- His arguments show us that debates around what freedom actually is can go in very strange directions.

- Remember how busy the Athenian citizens were next time you think there are too many questions on the ballot.

When people talk about freedom and democracy, they often trace the lineage of both back 2,000 years to the rocky shores of Greece or to the Senate of Rome. However, the freedom they had in the ancient world was a bit different than what we have today, with significant benefits for us.

The ancient democrats wouldn’t think you live in a democracy

According to French philosopher Benjamin Constant‘s lecture The Liberty of Ancients Compared with that of Moderns, the freedoms enjoyed by ancient peoples were fundamentally different than the ones we enjoy now.

He explains that Greek democracy:

…consisted in exercising collectively, but directly, several parts of the complete sovereignty; in deliberating, in the public square, over war and peace; in forming alliances with foreign governments; in voting laws, in pronouncing judgments; in examining the accounts, the acts, the stewardship of the magistrates; in calling them to appear in front of the assembled people, in accusing, condemning or absolving them.

That is to say, democracy and freedom meant popular participation in the political process. Any citizen might find themselves weighing the merits of war and peace, having to cast a vote on significant issues, or giving a speech on the need for more public spending to a crowd of hundreds. However, this increased democratic power came at a high personal cost. Constant explains:

…among the ancients the individual, almost always sovereign in public affairs, was a slave in all his private relations. As a citizen, he decided on peace and war; as a private individual, he was constrained, watched and repressed in all his movements; as a member of the collective body, he interrogated, dismissed, condemned, beggared, exiled, or sentenced to death his magistrates and superiors; as a subject of the collective body he could himself be deprived of his status, stripped of his privileges, banished, put to death, by the discretionary will of the whole to which he belonged.

For the citizen in ancient times who could say they were free, the freedom part was the act of voting. After that, little was assured. Socrates was put on trial for “not believing in the gods of the state”—an affront to our idea of religious liberty that didn’t strike the Athenians as strange at all.

Constant holds that idea up against the notion of personal liberty and representative government that we have today; we have rights that the state can’t violate and the state is to be managed by representatives working on our behalf. We have popular sovereignty, but not direct participation in the workings of the state. He calls this “modern liberty,” and it is a far cry from the Athenian system where you could be randomly selected to facilitate a meeting of the assembly.

This is a pretty significant change for such an important concept. How did it happen?

More slaves… more democracy?

Constant argues that the change was a practical one.

He points out that “modern” states simply cannot operate in the same way as ancient Athens did. After all, if the city of Chicago were to have an assembly that only 20 percent of the adult population showed up to, like in ancient Athens, they would have to find room for 300,000 people to have a meeting. The physical size of modern states also exacerbates the problem.

Likewise, he reaches the same conclusion as historian Anthony Everitt: that the widespread participation in Athenian Democracy, and the golden age of Athens by extension, was made possible by the city having a vast number of slaves doing all the necessary work. This assured enough leisure time for the citizens to actually gather and discuss all the matters of state on a regular basis. While automation might bring back such leisure time, for now, we are stuck with the need for representatives that can carry out day to day work for us.

On the other hand, the increasing variety of options available to people at the dawn of the modern age and impossibility of micromanaging everybody’s affairs lead to the idea of personal liberties that the state shouldn’t infringe on. Constant also thought the state would have a hard time trying to infringe on these rights anyway since all of the familiar means of repression were originally designed for small city states. When he said that in 1819 he might have been right.

He also reminds us that we have it pretty good with these modern liberties, as it allows the individual much more freedom in their personal lives at the cost of making our political participation less direct. Given that being part of a large electorate would leave our personal impact on the political process minor at best, he argues this is a fair trade.

So, is voting is overrated?

Not at all, as Constant argues that exercising our political liberty is the only way to guarantee personal freedom. What he rejects is the idea that a modern society requires ancient liberties, like direct participation all the time, to be free. Indeed, he blames the worst excesses of the French Revolution on attempts to bring the wrong liberties to France. Colin Woodard suggests in his book, American Nations, that a similar thing happened in the early years of the United States when the democratically elected John Adams restricted free speech.

The democracies that we live in today are entirely different from the ones in the ancient world. While it isn’t possible for everybody to serve as a magistrate or vote on every issue that affects society, it is possible for us to govern ourselves, choose representatives, and assure our freedoms through the democratic process. While we can’t be free in the same way as the Greeks were, we might have it better now anyway.