Marcelo Gleiser

Theoretical Physicist

Marcelo Gleiser is a professor of natural philosophy, physics, and astronomy at Dartmouth College. He is a Fellow of the American Physical Society, a recipient of the Presidential Faculty Fellows Award from the White House and NSF, and was awarded the 2019 Templeton Prize. Gleiser has authored five books and is the co-founder of 13.8, where he writes about science and culture with physicist Adam Frank.

There’s no escaping the death of loved ones. But that doesn’t mean we’re powerless in the wake of loss.

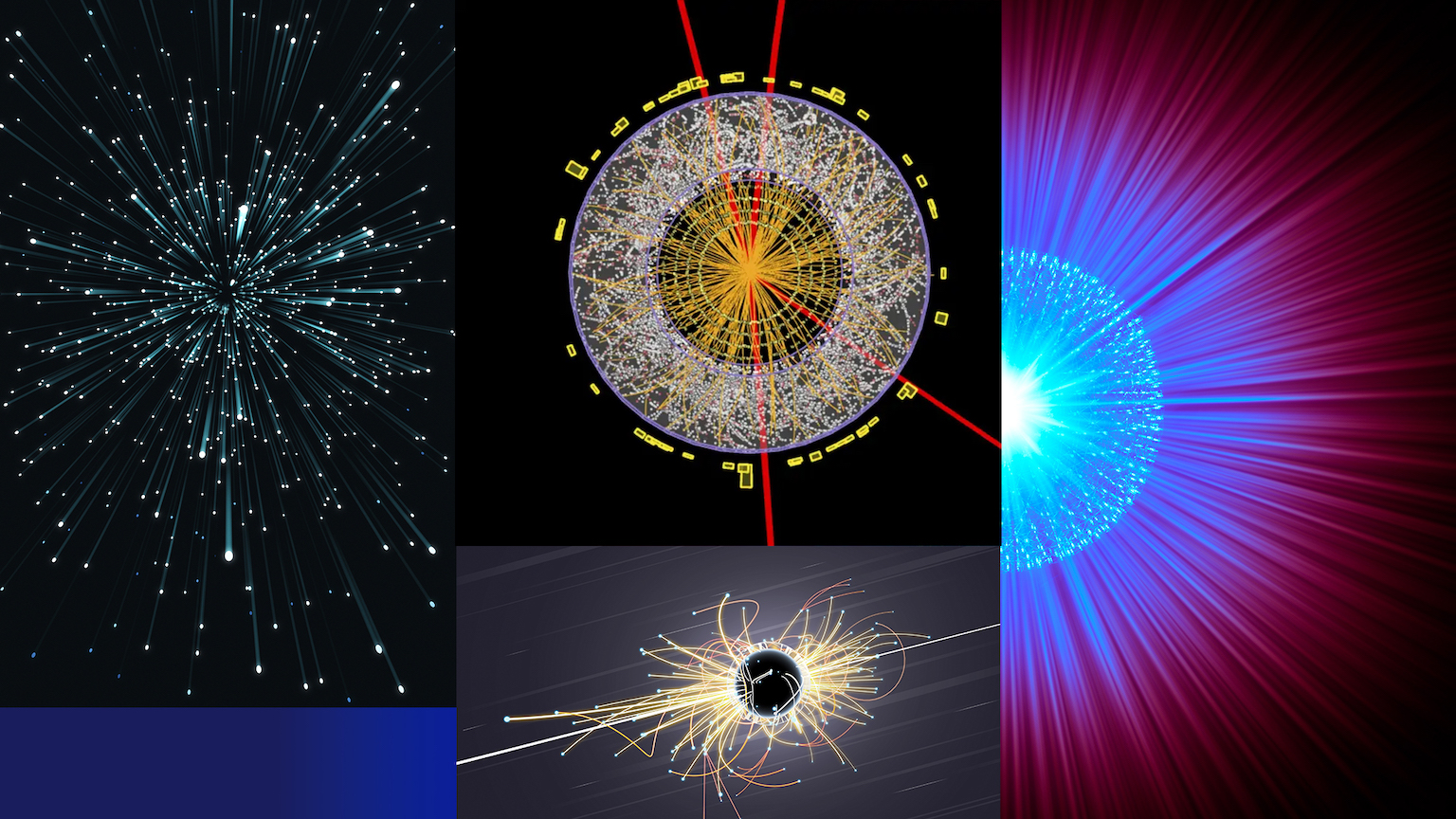

This technological feat changes our cosmic history.

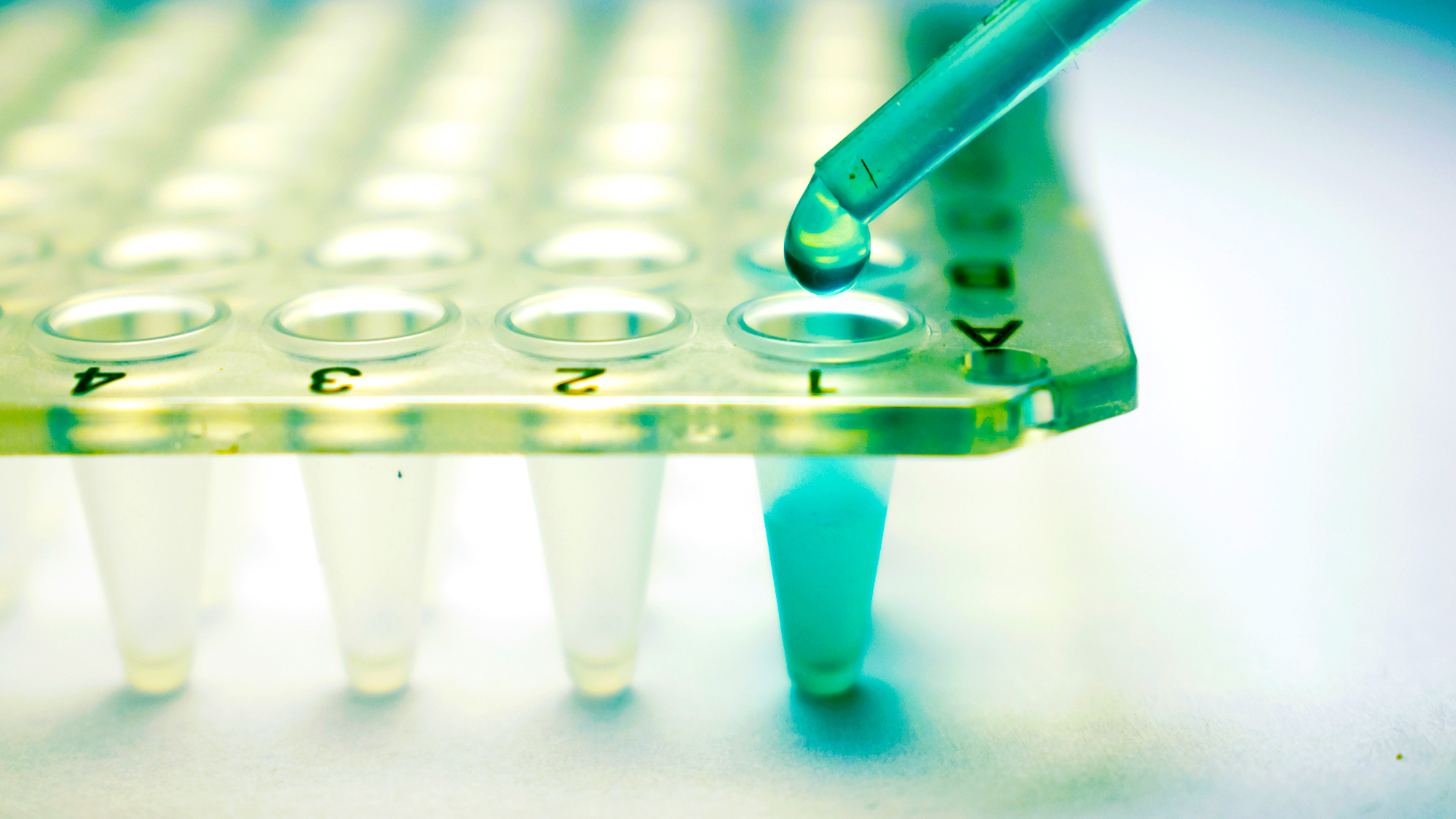

Synthetic biology has the power to cure and kill. Have we learned from our past mistakes?

Even the dictionary doesn’t get the definition right.

The false assumption the Multiverse relies on is that something which exists requires an explanation.

A second Enlightenment would have a far bigger task: Saving civilization itself.

Astronomy’s roots rest in the very origins of humanity. We have always looked to the skies for answers. We are starting to get them.

It is little more than a fancy excuse for escapist fantasizing.

Modern cosmology conjectures different possible fates for the Universe and thus for the end of time. Details depend on which model is right.

Humans are already so integrated with technology that the dream of transhumanism is a reality. Can we handle what comes next?

The engineer working on Google’s AI, called LaMDA, suffers from what we could call Michelangelo Syndrome. Scientists must beware hubris.

There is nothing more important to science than its ability to prove ideas wrong.

Science has come a long way since Mary Shelley penned “Frankenstein.” But we still grapple with the same questions.

All life forms, anywhere in our Universe, are chemically connected yet completely unique.

Singularities frustrate our understanding. But behind every singularity in physics hides a secret door to a new understanding of the world.

How efficiently could quantum engines operate?

Many people perceive the struggle to understand our Universe as a battle between science and God. But this is a false dichotomy.

From the tablets of the Babylonians to the telescopes of modern science, humans have always looked to the skies for fundamental answers.

Science and the humanities have been antagonistic for too long. Many of the big questions of our time require them to work closer than ever.

Most people have a distorted view of what being a scientist is like. Scientists need to make a greater effort to challenge stereotypes.

We cannot deduce laws about a higher level of complexity by starting with a lower level of complexity. Here, reductionism meets a brick wall.

The paradox of tribalism is that humans need a sense of belonging to be healthy and happy, but too much tribalism is deadly. We are one tribe.

Life is possible because of asymmetries, such as an imbalance between matter and antimatter and the “handedness” (chirality) of molecules.

The Universe has asymmetries, but that’s a good thing. Imperfections are essential for the existence of stars and even life itself.