The “friendship divide” explained: How your education affects your ability to connect

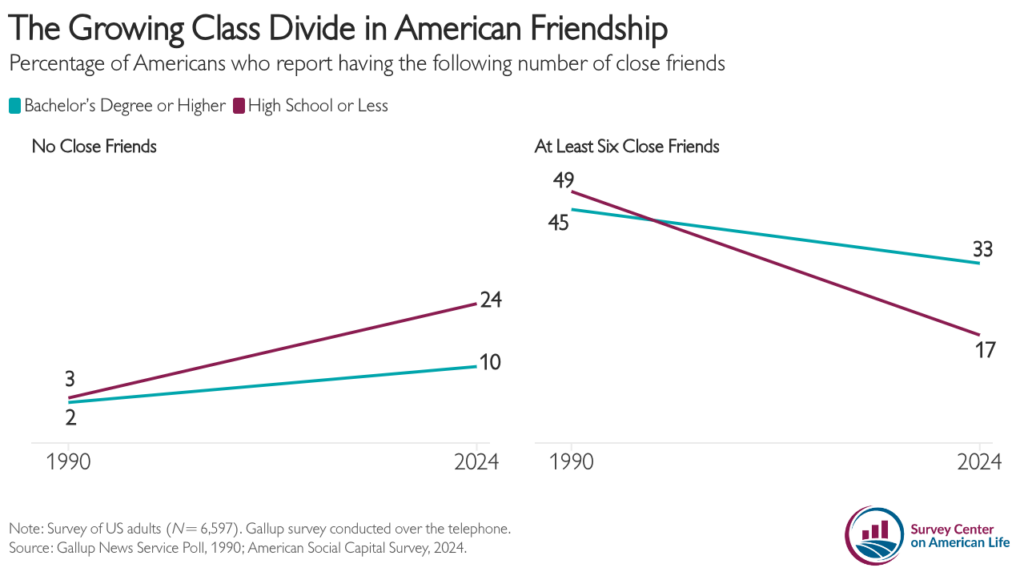

- Recent research led by Daniel Cox, director of the Survey Center on American Life, shows that college graduates tend to have more friends than those without degrees.

- The decline of community hubs, such as churches and civic groups, has disproportionately affected non-college-educated individuals, reducing their opportunities to form meaningful social bonds outside work and home.

- Cox suggests that to combat isolation, people need to engage more with their surroundings, participating in real-life activities and interactions instead of relying on technology to fill social gaps.

A lot has been written about the loneliness epidemic and the huge spike in isolation. It’s not just a post-COVID thing but has been in the works for a while. Study after study shows that, across a range of very different countries, people have fewer friends than previous generations, and they see those friends far less often.

But every country has its own version of this trend. In the US, the erosion of close social bonds is a many-headed beast driven by factors like geography, family, religious beliefs, and governmental policies. Another is education. It used to be commonly thought that people with a college degree were more likely to be lonely: The more educated you were, the fewer friends you tended to have.

According to a new study led by pollster Daniel Cox, that’s not true. Or, if it were true, it’s certainly changing now. To make sense of the “friendship divide” in the United States, Big Think spoke with Cox about his findings and suggestions for anyone suffering from friendlessness.

Office banter and lunch breaks

Cox recently co-authored a piece for The Survey Center on American Life called “Disconnected: The Growing Class Divide in American Civic Life” where he looked at the various trends and possible reasons behind loneliness, friendship loss, and disconnection. Who has the most friends? Why are some people more disconnected than others?

One of the most curious insights of the piece is that it shows a positive correlation between those who went to college and having more connections. In other words, if you go to university, you are more likely to have more friends than someone who does not. Cox highlighted two reasons for this.

The first is that college graduates find it easier to find a job and keep it when they get it. “College graduates have steadier working lives,” Cox said. “They’re less likely to be unemployed for prolonged periods of time.” That’s important not only for financial security but also for our sense of connection. As Cox put it, “Workplaces are critical ways Americans form fast friendships and lifelong friendships.”

To form any kind of meaningful relationship with someone, you have to spend a sustained period of time around them. In our normal, day-to-day lives, this isn’t possible. You might swap a few pleasantries with your cashier at the store, but you probably won’t invite them to your birthday drinks. You might enjoy talking about your holiday with your cab driver, but they likely won’t be at your wedding. Working eight hours a day in the same space helps facilitate these kinds of closer bonds.

Join our club

The second reason college graduates are more likely to have meaningful connections is the skills and mindset that college often provides.

For most students, college is more than just a rung on the career ladder — it also plays a fundamental role in shaping social lives. Educational institutions provide spaces where people form long-lasting friendships and tend to get involved in various activities, from joining a choir to playing as a quarterback, that help individuals build broader social networks. Those with college degrees, therefore, are naturally placed in environments that foster connection. As Cox tells Big Think, “The primary way that people make friends is through institutions… you’re a member of a sports league, you go to a college or university, and you meet friends there.”

As college students grew up, graduated, and joined the wider workforce, they left behind their fraternities and sororities but still retained their willingness to engage with what was around them.

“College graduates just seemed to be more involved [in things like] informal book clubs and meetups in the neighborhood,” Cox said.

The third space

When Cox talks about book clubs and meetups, he’s referring to something sociologists call the “third space.” In the late 1980s, Oldenburg defined the third space as anywhere you get to meet other humans, which isn’t your home or the workplace. At home, your first space, you live with your family or housemates. At work, your second space, you talk with colleagues and go to meetings.

Both, of course, have their place. Your home is essential to your well-being, and, as Cox argued, the second place of work is essential to forming connections. We need family, and we need to work. But we also need a third place. We need a playing field, a coffee shop, or a pub — a place where we can meet other people and exchange ideas. In other words, we need somewhere, which isn’t the home or the workplace, where we can shoot the breeze and relax a little.

Cox pointed out that college graduates are more likely to use these third spaces, but the problem goes beyond a simple educational divide; there is a wider decline in both the availability and use of shared community spaces. Historically, churches, unions, and other civic organizations served as hubs for social interaction, especially for Americans without a college degree. However, as these institutions decline — for whatever reason — so does the opportunity for those without degrees to form meaningful social bonds. Community spaces, once vital to the social fabric, have eroded, and this has disproportionately affected those with fewer resources.

Getting out to get connected

At the heart of Cox’s paper and Big Think’s interview is a simple message: We need to be around other people if those “people” are to become friends. College facilitates this in two ways: It allows you to join communities and activities, and it means securing longer exposure to a consistent workplace.

It’s popular, if controversial, to rail against the damage of technology. Technology is often blamed for many things, and not all of them fairly. But one of the legitimate concerns is, as Cox puts it, “We use technology to fill in the gap that at one point we would rely on another human being for.” Online spaces and forums are important to many people, but they are an inferior surrogate for real third spaces. We need to physically go to a bar, a ballgame, or a library. We need to reach out to each other and not to the smartphone.

In other words, if the problem is that the friendship recession is caused by increased isolation, we need to consciously and determinedly buck the trend. We need to, as Cox puts it, “just get out of the house and spend time around where you live.”