Can’t stop unwanted thoughts? Poor sleep may be to blame, study says

Credit: vlorzor via AdobeStock

- Poor sleep has been linked to many health problems, including diabetes, heart disease, obesity, depression, anxiety, suicidal thoughts and a shortened lifespan.

- A new study suggests that poor sleep also impairs the brain’s ability to suppress unwanted thoughts.

- The researchers suspect this is because not getting enough sleep disrupts the brain’s executive control functions.

Not getting enough sleep can wreak havoc on your mental health in ways that aren’t immediately obvious. Studies have shown that poor sleep can disrupt the brain’s ability to regulate cognitive and emotional regulation, exacerbating psychiatric conditions including anxiety, depression and bipolar disorder.

Now, new research suggests that poor sleep can also impair the brain’s ability to suppress unwanted thoughts. The study was published October 15 in the journal Clinical Psychological Science.

The researchers knew from past research that poor sleep impairs cognitive functioning — especially executive control, which describes your ability to manage and regulate cognitive functions. Because blocking unwanted thoughts from your mind would be a cognitive function that falls into the executive control category, the researchers hypothesized that poor sleep would reduce the ability to suppress intrusive thoughts.

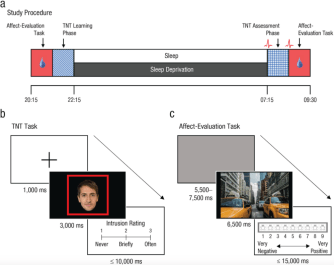

To test that idea, the researchers had two groups of participants take part in an overnight study. In the evening, all 60 participants were asked to memorize associations between pairs of images, each of which included a face and a scene that was rated either neutral or negative.

Both groups also learned a commonly used task in psychological experiments: the think/no-think paradigm. For the task, you’re shown an image, and, depending on the visual cue, you’re supposed to either think of something you’ve learned to associate with that image, or try to make your mind go blank.

Study procedures and tasks.Credit: Harrington et al.

The participants were shown faces in either a green or red frame. The green frame indicated “think,” meaning the participants should try to remember the image associated with that particular face. In contrast, red meant “no think,” make your mind go blank — and if a thought pops up, try to get rid of it.

Then one group slept for about eight hours, while the other didn’t sleep at all. In the morning, both groups completed the think/no-think task. The sleep-deprived group was far less able to keep intrusive thoughts out of their minds, despite the fact that both groups performed equally well the night before in a mock think/no-think task.

“Strikingly, the sleep-deprivation group suffered a proportional increase in intrusions of nearly 50% relative to the sleep group, revealing how deficient control may be a pathway to hyperaccessible thoughts,” the researchers wrote.

As the experiment went along, both groups became increasingly successful at suppressing unwanted thoughts. But the sleep-deprived group was less successful. The results showed a similar effect on relapses of intrusive thoughts (which were prompted by showing the same visual cue multiple times during the experiment): Both groups became better at suppressing relapses over time, but the no-sleep group had a harder time blocking relapses.

“…sleep deprivation diminished the cumulative benefits of retrieval suppression for down-regulating subsequent intrusions,” the researchers wrote. “Even after sleep-deprived participants initially gained control over unwanted memories and prevented them from intruding, they were consistently more susceptible to relapses when reminders were confronted again later compared with rested individuals.”

In addition to having difficulty suppressing intrusive thoughts, the sleep-deprived group also seemed to be more negatively affected by those thoughts, based on subjective reports from the participants and skin-conductance responses recorded by the researchers.

Although the study didn’t use brain imaging, the researchers noted that sleep deprivation may impair memory suppression by disrupting functional interactions between various parts of the brain, including “the [dorsolateral prefrontal cortex] (and possibly [medial prefrontal cortex]) and [medial temporal lobe] structures such as the hippocampus and amygdala during retrieval suppression, impairing inhibitory control over memory and affect, increasing intrusions, and decreasing affect suppression.”

The findings could shed light on how poor sleep interacts with psychiatric conditions, including major depressive disorder, schizophrenia, and obsessive compulsive disorder, to name a few.

“Insufficient sleep might increase memory intrusions while also nullifying the benefits of retrieval suppression for regulating affect,” the researchers wrote. “The onset of intrusive thoughts and affective dysfunction following bouts of poor sleep could create a vicious cycle whereby upsetting intrusions and emotional distress exacerbate sleep problems, inhibiting the sleep needed to support recovery.”

Fortunately, evidence suggests people can get better at suppressing intrusive thoughts. For example, a 2018 study found that college students who reported having experienced high levels of trauma were better at suppressing unwanted thoughts compared to students who had led relatively trauma-free lives.

“…given proper training, individuals can learn to better manage intrusive experiences, and are broadly consistent with the view that moderate adversity can foster resilience later in life,” wrote the researchers behind the 2018 study.

The team behind the recent study similarly noted that people with major depressive disorder might benefit from interventions where they learned strategies for suppressing unwanted thoughts.

No matter your ability to suppress unwanted thoughts, getting good sleep (seven to eight hours for most adults) is one of the most consequential health decisions you can make. Harvard Medical School offers eight tips for getting better sleep:

- Exercise at some point during the day.

- Reserve your bed for sleep and sex—not work or TV.

- Keep the bedroom comfortable.

- Start a sleep ritual.

- Have a bedtime snack—but not too much.

- Avoid alcohol and chocolate before bed.

- Wind down before going to bed.

- See your doctor about what’s keeping you up at night.