What’s causing the rise of hoarding disorder?

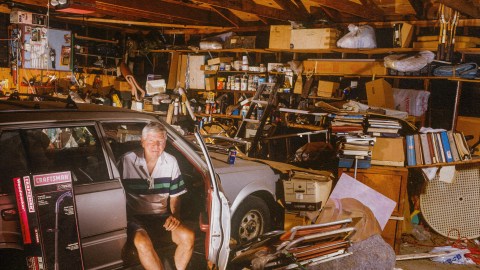

Reality TV doesn’t need to do much to sensationalize hoarding. Like rubberneckers at a traffic accident, we gaze in horror at “goat paths” hacked between mounds of newspapers, greasy pizza cartons, bills, checks, mustard packets, broken gadgets, old T-shirts, and stained Tupperware. Crawling with rodents and cockroaches, covered in mildew, mold, and bacteria, these mounds are a fire hazard (according to one study, they cause 24 percent of all avoidable fire deaths) and a fall hazard. They build a wall of shame that blocks the entry of family, friends, even a plumber or electrician. How can people live like this? we murmur.

But many hoarders don’t see their behavior as disordered, and psychology didn’t either—at first. In 2013, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, the holy book of psychiatric diagnoses, was revised to list severe hoarding as a disorder in its own right. To meet the diagnostic criteria, someone must have acquired an unmanageable, even hazardous number of possessions that appear to be useless or of limited value—yet would cause them severe distress if discarded.

The original understanding of hoarding, however, had nothing to do with clutter; it was financial avarice. King Midas hoarded gold, as did the tight-fisted clergy who, Dante wrote, would be condemned to the fourth circle of hell. Only in the twentieth century did people begin engaging in the eccentric over-accumulation of random, not terribly valuable stuff.

At first, it was called Collyer’s syndrome, in honor of Homer and Langley Collyer, brothers who, between 1909 and 1947, slowly buried themselves in their family mansion in Harlem, filling it inch by inch. By midcentury, as mass production and a postwar economic boom made it possible for people of modest means to acquire more and more objects, Collyer’s syndrome became more widespread. Psychologists decided that hoarding must be a subtype of obsessive-compulsive disorder: a repeated, ritualized action intended to ward off anxiety.

That categorization held for decades—even though clinical hoarding affects up to 6 percent of the world population, twice as many as OCD. A 2010 review by David Mataix-Cols at King’s College London noted that at least 80 percent of people who engaged in extreme hoarding didn’t meet the criteria for OCD. They were more prone to depression than those with OCD. They had more difficulty making decisions. They were far less likely to be aware of their behavior as a problem. Genetic linkage studies showed a different pattern of heritability than OCD, and brain scans showed a different pattern of activation. Drugs that were successful in treating OCD were not effective for hoarding.

Finally, in 2013, hoarding disorder was sprung free of the OCD category. And it can be connected to an array of causes as motley as the stuff that gets hoarded. It shows up on a continuum, spanning everything from an overcluttered home that’s spun out of control to abject squalor. It can extend to the accumulation of live animals (though that’s a very different proposition).

In families with two or more members who hoard, researchers have identified an allele on chromosome 14 (in Doberman Pinschers, hoarding’s been linked to chromosome 7). “More than 80 percent of our subjects reported a first-degree relative with similar problems,” note Randy Frost and Gail Steketee, pioneers in this research, in their book Stuff: Compulsive Hoarding and the Meaning of Things. Hoarders might inherit different ways of processing information, they suggest, or “an intense perceptual sensitivity to visual details… [that] give objects special meaning and value to them.”

Other studies suggest non-genetic causes. Hoarding can also accompany certain traumatic brain injuries, Tourette’s syndrome, ADHD, neurodegenerative disorders, generalized anxiety disorder, clinical depression, and dementia. Childhood poverty, interestingly enough, does not seem to be connected with hoarding. But researchers have found a possible link between hoarding and PTSD among Holocaust survivors, and late-onset hoarding has often been linked to loss or trauma. The psychological understanding is that objects are gathered in a futile attempt to fill emotional emptiness—piled up like a barricade to protect oneself against an uncertain future.

If you zoom out from that intimate pain, though, there’s also a big-picture theory: Hoarding is the natural consequence of a consumer society glutted with stuff and running out of landfills.

In “Neurohistory in Action: Hoarding and the Human Past,” the historian Daniel Lord Smail suggests that we stop thinking of biology and culture as separate causes. “Gene expression is intimately tangled up with cultural and individual life circumstances,” he points out. Couldn’t the rise of compulsive hoarding be caused by the ways our physical selves interact with a changing material environment? When we started processing our food, for example, we no longer needed wisdom teeth—so our mouths grew too small to accommodate them. “Social forms and behavioral patterns sculpt the body,” Smail writes.

Rather than see an object as a member of a large group (say, one of 42 black T-shirts), a hoarder sees it as singular, unique, special.

Monkeys, crows, squirrels, kangaroo rats, and honeybees all hoard—just as humans have for millennia—as an adaptive way to survive a cold winter or a famine. That is not the kind of hoarding that makes it to a reality TV show. “The compulsive hoarding of useless things seems to be characteristic of only the last century or two—and primarily the last few decades,” Smail notes.

In other words, something has changed—in history and culture—to cause hoarding to emerge as a prevalent psychiatric disorder. Objects have taken on, for those who hoard them, individual personalities with outsized emotional significance. They cannot be casually discarded; they are woven into the person’s very sense of self, promoting comments like, “If I throw too much away, there’ll be nothing left of me.”

Acquisition is the first half of the disorder. People fall in love with stuff they don’t immediately need because it’s free, or it reminds them of a particular experience, or they might need it someday, or they could transform it in some cool way and increase its value. These objects accumulate, and people resist parting with them because of their perceived potential, or their sentimental significance, or their triggered memories, or because it’s wasteful to pile up a landfill with some perfectly good object somebody might need someday. Or because the person who’s hoarding simply doesn’t like being told what to do with their stuff.

Even if they want to downsize (which is rare), there’s the overwhelming difficulty of sorting through the mess. People with severe hoarding disorder tend to be easily distracted and have a hard time focusing and concentrating. Paradoxically, they also tend to be perfectionists, so they’ll put off making decisions rather than risk being wrong. And when it comes to their own stuff, they don’t categorize by type. Rather than see an object as a member of a large group (say, one of 42 black T-shirts), they see it as singular, unique, special. Each black T-shirt is perceived apart from the others and carries its own history, significance, and worth. It’s not even categorized for storage (folded with other black T-shirts in a T-shirt drawer), but rather placed on a pile and retrieved spatially (that particular black T-shirt lives about four inches from the bottom of the corner stack). This leads to a deep aversion to someone touching the piles or sifting through them, unwittingly destroying the invisible ordering system.

As with any condition that becomes a collective fascination, there’s a chicken-or-the-egg question: Is hoarding disorder increasing or has an increase in media coverage just made us more aware of it? Estimates suggest that as many as 19 million Americans have a hoarding disorder. The first task force on hoarding formed in 1989 in Fairfax County, Virginia. There are now more than 100 such organizations in the U.S. By 2020, more than 15% of the U.S. population is expected to be 65 or older—prime age for hoarding. According to the American Psychiatric Association, hoarding disorder affects three times as many people ages 55 to 94 as it does those ages 34 to 44. The disorder may show up in adolescence, but it’s often intensified in older age, exacerbated by bereavement, divorce, fuzzy thinking, or financial crisis.

People are living longer and aging at home, where they’re free to amass as much stuff as they like. Sometimes that tendency was held in check by a spouse who’s now gone. Sometimes what’s hoarded are the deceased spouse’s belongings. Or those of a child who has long since grown up and moved out. At a point where people are losing their independence—their work, status, connections, sensory acuity, physical strength, and mental sharpness—hoarding can be a way to shore oneself up, to feel safe, consoled, prepared.

An entire industry has sprung up around hoarding: psychologists, researchers, social workers, public health workers, professional organizers, fire marshals, biohazard cleanup companies, haulers. Why does it bother us so much? There’s an instinctive recoil from the pests and contaminants, of course, not to mention the dreaded fights and physical labor if the person who’s hoarding is a family member.

The disorder’s not just incomprehensible to the rest of us, but intractable. People who hoard are often intelligent, well-educated, and creative, and they don’t want to be “fixed.” If their home reaches a point where city officials force help, it’s likely to be filled again soon after it’s been emptied.

There might be another reason, though, for the general recoil. Several scholars have suggested that hoarding hits a little too close to home. We all do daily battle against an excess of stuff. It flows into our homes, brought by FedEx and the U.S. Postal Service, snagged on Amazon, Facebook Marketplace, Freecycle, or a yard sale, inherited or handed down. It piles up in closets, basements, and garages. Almost 10 percent of American households are renting at least one storage space, often for an overflow of stuff, according to a 2015-16 Self Storage Industry Fact Sheet. It is now possible for every American to stand comfortably, at the same time, under the total canopy of self-storage roofing.

Those of us terrified by this prospect watch episodes of Hoarders or Hoarding: Buried Alive and race to declutter, muttering the KonMari principles as we hunt for sparks of joy amid the detritus. Perhaps Marie Kondo would not have become a multimedia phenomenon in the madly collecting Victorian Age, with its precious cabinets of curiosities, nor in the postwar ’50s, with brightly colored toys and gizmos flying off the factory conveyor belts. But now we are glutted with stuff—and uneasy about the consequences.

This article appeared on JSTOR Daily, where news meets its scholarly match.