“Zombie-like” prion proteins appear to link Alzheimer’s and Down syndrome

- People with Down syndrome who live beyond age 40 develop progressive dementia similar to people with Alzheimer’s disease.

- In the last few decades, scientists have found that the brains of people with Alzheimer’s contain abnormal clumps of pathogenic, self-propagating proteins called prions. New research shows the same is true for those with Down syndrome.

- Unfortunately, drugs that target these protein clumps are unsuccessful at treating Alzheimer’s, suggesting that our understanding of the disease is incorrect.

Before the 1950s, the life expectancy for people with Down syndrome was 12 years, and little was known about the health challenges these individuals would face in adulthood. Fortunately, over the last seven decades, life expectancy has risen to 60 years, and with that increase, scientists have discovered more about the pathology of the extrachromosomal disorder.

Unexpectedly, this expanded lifespan has provided insight into other disorders, such as Alzheimer’s disease. And recently, a team of neurologists at UCSF discovered that people with Down syndrome have abnormal brain proteins with prion-like features — just like people with Alzheimer’s do.

The discovery of Alzheimer’s

In 1901, Auguste D. was admitted into the Community Psychiatric Hospital in Frankfurt. Auguste was 50 years old and experiencing profound memory loss and aggressive, emotional changes. During the same period and at the same hospital, a young physician named Alois Alzheimer was working to develop a technique to diagnose dementia by analyzing brain tissue. When Auguste passed away in 1906, Alzheimer performed an autopsy and discovered abnormal protein formations in her brain, which he believed to be connected to Auguste’s mental illness.

As Alzheimer’s diagnoses became more common, for the better part of the 20th century, scientists sought the cause of these problematic proteins. Many researchers suspected there was a genetic component to Alzheimer’s because it seemed common within families. However, the human genome is vast, and the tools for analyzing it at the time were primitive.

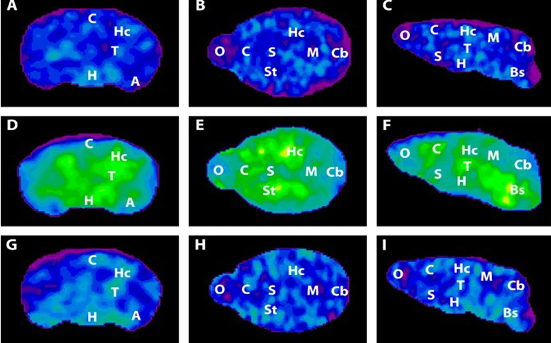

By the 1980s, a clue had arrived from an unexpected source. For the first time in history, people with Down syndrome were living to late adulthood. Over half exhibited the abnormal proteins and symptoms of Alzheimer’s by their sixth decade of life, compared to only 10% of the general population. Down syndrome and Alzheimer’s seemed to share a similar pathology, which narrowed down the search for a genetic cause considerably.

The 21st chromosome

People with Down syndrome, also called Trisomy 21, possess three copies of chromosome 21 (whereas most people have two), and scientists suspected that a genetic cause of Alzheimer’s must be hidden in that chromosome, given the greater prevalence of Alzheimer’s symptoms in those with Down syndrome. So they began searching the chromosome for the amyloid-beta gene, which encodes a protein that aggregates to form one of the abnormal clumps found in the brains of Alzheimer’s patients. In 1987, they found the amyloid-beta precursor protein (APP) gene. The discovery of the gene allowed scientists to study the protein’s behavior with a new level of scrutiny. Surprisingly, they discovered that it behaved like a prion.

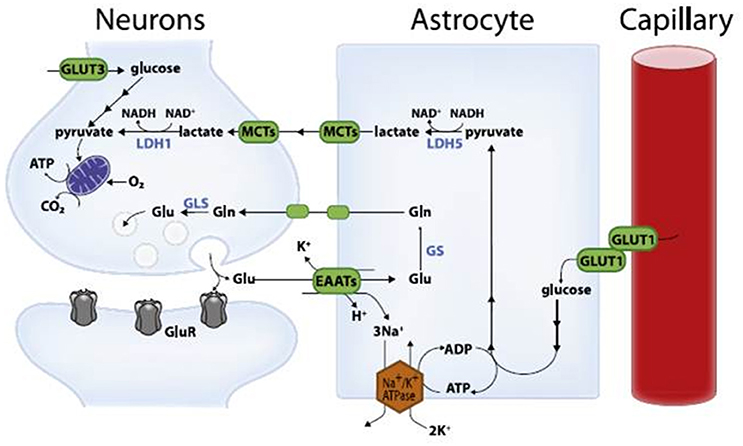

Prions are the zombies of the protein world. When one of these malfunctioning proteins interacts with a normal version of that protein, it warps it into a prion, resulting in a self-perpetuating cascade. Prion diseases often develop slowly as the pathogenic proteins accumulate and form aggregates throughout the brain over decades.

As scientists learned more about the pathology of prion diseases (like Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease and “mad cow” disease), it became increasingly clear that Alzheimer’s shares a similar pathological mechanism. By the early 21st century, evidence overwhelmingly suggested that prion-like behavior by the amyloid-beta peptides is responsible for the abnormal aggregations associated with Alzheimer’s.

Down’s syndrome also features prions

Due to the similarity between Alzheimer’s and Down syndrome, one would expect prions in the brains of people with Down syndrome. And that’s exactly what a recent study published in PNAS found: The same amyloid-beta prions (as well as tau prions, which are also found in Alzheimer’s) were detected in the brains of Down patients.

However, the problem that likely will plague this research is the same as what has been plaguing Alzheimer’s research: Drugs that clear out these abnormal protein aggregates have little to no effect on Alzheimer’s symptoms, suggesting that our entire understanding of the pathology of Alzheimer’s is incorrect.