An untold story of LSD psychotherapy in communist Czechoslovakia

Hana K.’s third LSD experience was terrifying. Initially, the images that flashed before her eyes were beautiful: fountains of colors, fields of tulips, peacock feathers. Then they turned dark: monsters, claws, demonic eyes, vampires. She saw kings and beggars dead, buried, eaten by worms, providing food for animals and eventually for other people. “Imagine the countless atoms of our ancestors in this perpetual motion!” she cried aloud, describing everything she saw to another patient, sitting beside her bed.

Hana had a troubled life. Born in 1949, she grew up in a town south of Prague, in a family crushed by poverty. When Hana was a child, her father drank and her spiteful mother often hit her for wetting the bed. At school, classmates teased her for wearing secondhand clothes, which were often damp because she was too shy to ask permission to go to the bathroom. In her teens, she was lonely and angry, so tormented by vivid dreams of murdering her enemies that she asked to be hospitalized. At 18, she married a boy she barely knew, separated from him after four months, and then tried to kill herself by swallowing 30 sleeping pills.

After that, Hana’s existence was a series of mind-numbing jobs, more suicide attempts, and stays in the massive, 2,000-patient Dobřany mental hospital, 60 miles southwest of Prague. Although intelligent, she was also considered hopelessly psychotic. But in 1969, when she faced another return to Dobřany, Hana told her family doctor she would rather kill herself — and this time the doctor referred her to the 112-bed clinic at Sadská, a facility east of Prague specializing in repeated sessions of LSD psychotherapy, directed by the psychiatrist Milan Hausner (1929–2000).

Hausner originally doubted that she could be helped. But as he listened to a recording of Hana’s third LSD session, he saw some hope. “The most pronounced aspect of this session is her archetypal regression into the realm of antiquity and to the very beginnings of humanity,” Hausner later wrote. “Hana is beginning to formulate a new attitude toward death and eternity.”

Over the next six months, Hana had 20 more sessions of LSD. Hausner told her that she might need 60 to be cured.

As Sarah Marks and others have detailed, psychiatry in communist Europe was not merely an obedient lapdog to the Pavlovian conditioning promoted by the Soviet Union. It was far more varied and complex — and certainly one of its most unusual chapters concerns the use of LSD psychotherapy in 1960s Czechoslovakia, when that country’s progression to a more humane government, its increasing openness to Western Europe, and its developments in psychiatry and pharmacology all coincided with a worldwide curiosity about psychedelic drugs.

The drug was a “probe into the subconscious,” Hausner wrote — and “the probe goes very deep, often into the first days of life, if not further.”

Until recently, LSD therapy in Czechoslovakia was known mainly through the work of Stanislav Grof (1931–), who practiced at Prague’s Psychiatric Research Institute, moved to the U.S. in 1967, and is today celebrated as one of the founders of transpersonal psychology. But dozens of other Czech and Slovak psychiatrists also used LSD in psychotherapy, and the most dedicated and outspoken of them was Hausner, who supervised more than 3,000 LSD sessions, published research in more than 100 articles and books, and yet remains largely unknown, even in his homeland.

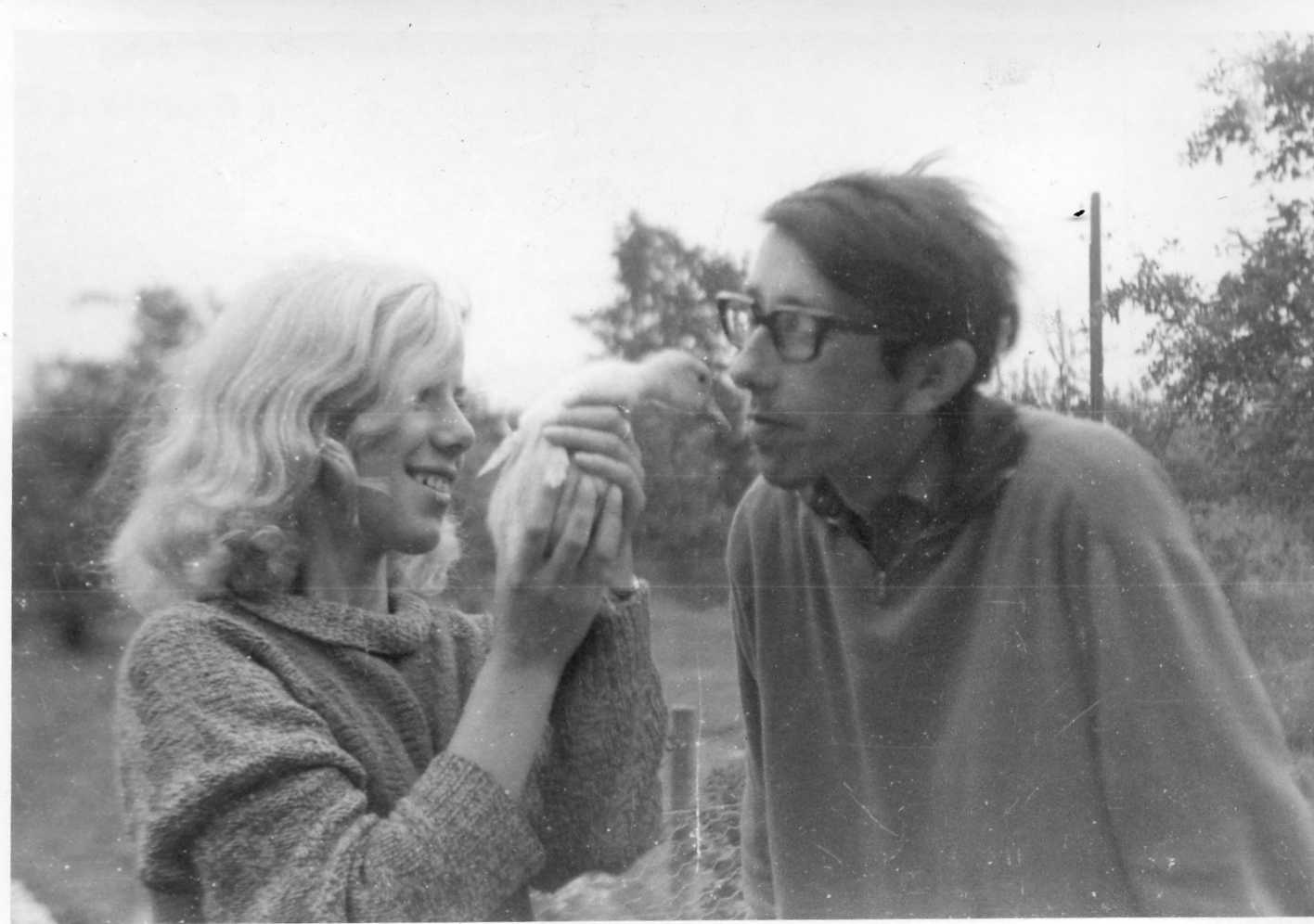

Hausner grew up in Prague, the only child of an insurance clerk and a pharmacist. He was drawn to the healing arts early: In May 1945, during the uprising against Nazi Germany’s occupation of Czechoslovakia, he cared for fighters at Prague’s barricades. Germany had closed Czech universities during the six-year occupation, so after the war, the need for young doctors was acute, and in 1948 — the same year the communists seized control of Czechoslovakia’s government — Hausner enrolled in medicine at Prague’s Charles University. After graduating in 1953, he practiced psychiatry in various places around the country, including a children’s hospital. He married Zdena Procházková, a medical statistician, completed his compulsory military service, and by 1958 was back in Prague, busily working on several psychiatric wards, often traveling from one hospital to another on the same day.

Hausner first experienced LSD in experiments conducted by Jiří Roubíček, likely in 1954. Roubíček, a neurologist, was interested in comparing the brain-wave patterns of schizophrenic patients with those of healthy subjects undergoing a “model psychosis” induced by LSD, which he obtained from Sandoz and started experimenting with in 1952. Since LSD produces mind-altering effects in tiny amounts without inflicting physical harm, Roubíček’s superiors considered it safe, and many young psychiatrists became his test subjects. (Czech doctors have a tradition of self-experimentation: The Czech medical society is named after Jan Evangelista Purkyně, a 19th-century physiologist who asserted that one learns best from direct experience and studied the effects that he underwent after ingesting such substances as digitalis and belladonna.) Unfortunately, it’s not known what Hausner thought of his own LSD experiences, as he did not describe them in his writings.

In the late 1950s, Hausner started conducting his own medical research, publishing a study of his application of the new antipsychotic drug chlorpromazine combined with electroconvulsive therapy (ECT). Increasingly, however, he was interested less in biological psychiatry and more in psychotherapy — a controversial discipline, as it was often associated with Freudian psychoanalysis, which communists considered unscientific, individualistic, and likely to bankrupt national health insurance programs. In 1959, Czech ideologues denounced Ferdinand Knobloch (1916–2018), the head of psychiatry at Charles University’s medical-faculty polyclinic, for advocating the use of psychotherapy to treat neuroses, and Hausner came to his defense. In the journal Czechoslovak psychiatry, Knobloch assured his readers that he was developing a “materialistic” psychotherapy, with measurable results, and Hausner provided a survey of recent Soviet medical literature showing that Russian doctors already were practicing psychotherapy in various forms, using suggestion (often with hypnosis) and persuasion, in an effort to fully understand “the personality of socialist man in unity with the socialist environment.” (Hausner read and spoke Russian, along with English and German.) Czechoslovakia held an international congress on treating neuroses later that year, so a wider acceptance of psychotherapy was already underway. But Knobloch likely appreciated Hausner’s support, because he soon hired Hausner to work at the university polyclinic.

Between seeing patients, Hausner wrote his first book, “The Mentally Ill Among Us” (1961), a guide to the mental-health system for patients and their families that told the story of a young man’s psychotic break, his treatment through medication and psychotherapy, and his return to work. In the preface, Hausner noted that Czechoslovakia’s third Five-Year Plan (1961–1965) called for wider treatment of “nervous diseases,” and he hoped that his readers would learn that “mental illness does not equal disgrace, but can be successfully treated like any other physical illness.” (Hausner’s compassionate book was so popular that it was republished in 1969, 1978, and 1981.) During this time, he also began paying privately to undergo psychoanalysis, perhaps with Knobloch, as part of his training to become a psychoanalyst himself. Most fatefully, though, he became interested in treating patients with LSD, newly available from Czechoslovakia’s government laboratories.

In 1956, chemists at the Research Institute for Pharmacy and Biochemistry in Prague filed a patent for a new process for making LSD, and in 1959, the ministry of health gave the institute permission to begin producing the drug, trademarked Lysergamid, “primarily for experimental purposes.” So Hausner devised an experiment. In 1954, R. A. Sandison and other British doctors had reported benefits in neurotic patients who received small-to-substantial doses of LSD (25 to 400 µg, or micrograms) in conjunction with individual psychotherapy, applied repeatedly over several months — a method that Sandison later called “psycholytic” therapy. Hausner wondered if this would work in groups. Through the university, he knew Vladimír Doležal, a medical doctor and chemist specializing in toxicology, and they proposed using LSD in a therapeutic community established by Hausner’s boss.

Even under communism, Czechs with “bad nerves” were typically treated with baths at the country’s opulent 19th-century spa resorts.

At the polyclinic, Knobloch had become intrigued by the self-defeating behavior of his neurotic patients, so he’d developed a retreat for them on a state farm in Lobeč (35 miles north of Prague), modeled on the therapeutic community for traumatized soldiers that Maxwell Jones had established near London in 1947. Even under communism, Czechs with “bad nerves” were typically treated with baths at the country’s opulent 19th-century spa resorts, and Knobloch wanted to prove that he could help more people at less cost. At Lobeč, 15 men and 15 women spent several hours every day working on the farm, and several additional hours with a rehabilitation aide engaged in group discussions or various types of therapy, producing art or music or acting out events from their lives via psychodrama or “psychogymnastics,” a nonverbal exercise incorporating movement and mime. A psychiatrist from Prague visited to direct individual and group psychotherapy only once or twice a week, so the patients effectively became cotherapists, a design that Hausner tried to duplicate at Sadská.

In their experiment, Hausner and Doležal gave 11 neurotic patients 100 µg of LSD in conjunction with six hours of individual psychotherapy; seven got 50 µg and group therapy, and seven got saline as a control. After several weeks, the patients who’d received LSD and individual therapy showed the most improvement, displaying new insights and changed attitudes in their relationships with staff and other patients. Those who received LSD in the group had the worst results: “Patients were more concerned about their unusual experiences than to expose them to the therapeutic effect of the collective.” It was a modest study, but the first on LSD psychotherapy to appear in the Czech medical literature.

Other Czech doctors were starting to use the drug. Stanislav Grof began psycholytic therapy with neurotic patients at the Psychiatric Research Institute in 1961, and that year the authorities approved Lysergamid for outpatient psychiatry, encouraging other doctors around Czechoslovakia to test it in their own practices. Individual psychotherapy expanded, and soon it was possible to discuss concepts that were essentially Freudian: In 1963, Hausner and Doležal published a remarkable how-to guide for hallucinogens in the journal Czechoslovak psychiatry, citing the West German psychiatrist Hanscarl Leuner’s contention that such drugs “reawakened psychic dynamics” by evoking “age regression going to the first years of life,” “re-living of forgotten traumatic events,” and providing “abreactive emotional release with subsequent insight.” They outlined radical techniques, some borrowed from Leuner and other Western LSD doctors, that they used at Lobeč: getting patients to write out their autobiographies, using family photos to encourage associations, having the doctor play characters perceived in patients’ hallucinations, and even recruiting other patients to assist with the sessions. Hausner and Doležal quoted their patients endorsing LSD therapy, included samples of patients’ artwork, and claimed that after a year, 75 percent of their patients receiving LSD and individual therapy had improved, although the best results were in those who’d combined such therapy with a stay at Lobeč, where they could practice insights acquired from their LSD experience.

Through such research, Hausner established contact with Leuner, who became the principal advocate for psycholytic therapy after Sandison moved on from LSD in 1964. Hausner started getting published in international journals, Czechoslovakia began permitting academics to travel to capitalist countries, and in August 1964, Hausner summarized his Lobeč work at the Sixth International Congress of Psychotherapy in London. By 1965, Czechoslovakia’s authorities had approved commercial production of its LSD, and Hausner wrote a paper — published in English — for the state pharmaceutical export firm, noting that Lysergamid was indistinguishable from Sandoz’s product and describing its effectiveness in outpatient psychiatry. He would run 104 sessions with 65 patients, using doses of 50 to 300 µg, and found LSD was “a valuable means for deepening and accelerating the psychotherapy.” (Perhaps reluctant to limit foreign interest in Lysergamid to therapeutic communities, Hausner downplayed his Lobeč research, writing that he’d seen “no impressive differences” in results with outpatients.)

Hausner had credentials, contacts, and a steady supply of LSD. He was ready to apply everything that he’d learned at a clinic of his own.

The psychiatric clinic at Sadská, a town of 3,000 residents 40 miles east of Prague, consisted of a pair of two-floor pavilions originally constructed in the 1920s as a retreat for postal employees to enjoy a nearby lake and mineral spa, or walk along the Elbe River and through the Kersko forests. To meet the growing demand for psychiatric care, the ministry of health acquired the facility and began admitting patients in 1962. But by the autumn of 1965, Sadská’s chief physician was losing his eyesight. The clinic was affiliated with Charles University’s faculty of medicine, so Hausner, then 36, got the job, and he quickly made changes.

Pavilion A remained devoted to standard psychiatry for inpatients suffering issues from hysteria to psychosis. But Hausner had Pavilion B remodeled as an open ward to suit a therapeutic community. He selected some 50 inpatients for it, to stay six to eight weeks, and from them, he chose one or two groups of 12 to 14 patients who he thought were most likely to benefit from LSD, to stay six months. As at Lobeč, the patients spent mornings laboring in the forest or in the clinic’s garden and workshop, afternoons in group discussions, and evenings hearing lectures, creating dances or plays, or watching films. But with his own facility, Hausner could fully implement psycholytic therapy, and every day several patients underwent LSD.

The drug was usually delivered by injection to control the dosage, and before breakfast so the patients wouldn’t be hungry in the middle of their trip. Sessions were conducted in the patients’ rooms — LSD groups were on the ground floor — and the patients were accompanied by a sitter. Outpatients also came to Sadská for “weekend therapy,” undergoing LSD and individual or group analysis and returning to work on Monday. Like the inpatients, these visitors underwent dozens of treatments: one 42-year-old male received 300 µg 37 times in 18 months.

“Talk openly about everything that comes to mind while using the substance,” Hausner advised. “The purpose of sitting is not to ‘extract’ experiences that you would not discuss in a completely awake state.”

Hausner wrote up a guide for patients, introducing them to psycholytic therapy. Many instructions were typical of clinics elsewhere — he advised patients to keep their eyes closed while on LSD and to accept unpleasant or frightening episodes, as they might reveal the sources of their psychological difficulties — but others seemed worded to reassure patients who had lived under totalitarianism. “Talk openly about everything that comes to mind while using the substance,” Hausner advised. “The purpose of sitting is not to ‘extract’ experiences that you would not discuss in a completely awake state.”

He also wrote detailed instructions for the staff. Nurses were to supervise patients filling out the numerous questionnaires, to conduct art and occupational therapy, and to sit with patients during LSD sessions. Some patients might undergo psychotic episodes, he warned: “Remember that kindness, an effort to understand seemingly bizarre behavior, and minimal restraints can usually eliminate even the most violent manifestations.” Any doctor or therapist working with LSD was required to have at least three experiences with the drug themselves so that they could better understand their patients, and nurses had the option to undergo LSD as well. “When work started at Sadská, the personnel took a very skeptical attitude to the whole undertaking,” Hausner told a reporter, but most employees came around. “Their first eye-opener is that as ‘normal’ people they are not so very different from the patients under LSD intoxication. This discovery breaks down the barrier of prejudice in them.”

The LSD therapy at Sadská was also greatly influenced by Zbyněk Havlíček (1922–1969), a psychologist and surrealist poet who had worked at the Dobřany mental hospital in the 1950s and was at Sadská when Hausner arrived. Fascinated by psychoanalysis, Havlíček considered LSD a “miracle” compared to the mind-numbing drugs issued by most psychiatrists, and he ran many of the early psycholytic groups at Sadská, interviewing patients while they were hallucinating.

In letters to his girlfriend, Havlíček described his method in detail, playing with patients’ symptoms “like a bullfighter, waving a red cloth to their statements,” probing their visions and memories and finding connections in their biographies and patterns of behavior. This LSD analysis apparently worked: Hausner reported that 80 hospitalized patients underwent psycholytic therapy at Sadská in 1966, mainly suffering from neuroses, sexual disorders, and psychosomatic syndromes that hadn’t responded to other treatments for years, and 47 of them improved enough to be discharged. “The more sessions, the better the results,” Hausner said: patients who improved significantly had an average of 12 sessions (average dose 250 µg), while those showing no improvement had an average of six.

This was good news at a time when moral panic about LSD was cresting elsewhere. In April 1966, a few days after the New York Times reported that a man claiming to be “flying” on LSD had stabbed his mother-in-law to death, Sandoz announced that it was stopping all distribution of its product, and therapists from the U.S., the UK, Italy, and other countries started visiting the Sadská clinic, hoping to buy Lysergamid. Stanislav Grof knew many prominent LSD doctors after presenting his own psycholytic research at a conference in New York, and he brought several of them to Sadská, including Harvard’s Walter Pahnke. But the panic elsewhere reached Czechoslovakia, too: The communist daily Rudé Právo ran an article denouncing LSD as a “new god” that had unleashed madness in the West, and Hausner had to respond. No misuse of Lysergamid had occurred in Czechoslovakia, he assured readers; only trained psychiatrists could request the drug after approval by a special committee of the ministry of health. (Hausner was the committee secretary, and he directed foreigners’ inquiries to the state export company.) Besides, LSD was too valuable a tool to be outlawed. The drug was a “probe into the subconscious,” Hausner wrote — and “the probe goes very deep, often into the first days of life, if not further.”

This was an extraordinary claim, especially for the pages of the official Communist Party newspaper, but it did reflect what the doctors were seeing. Hausner reported elsewhere that two-thirds of his LSD patients “relived phantasies concerning their birth, intrauterine life, ‘birth trauma,’ [or] first events of the sucking age.” At an October 1966 conference in Amsterdam, Grof theorized that LSD brought forth constellations of emotionally charged, condensed experiences (COEX), individual to each patient’s life, and these earliest memories or fantasies lay at the core of each COEX system, providing a key to understanding the patient’s problems. Havlíček, the Freudian, disagreed, arguing that such experiences were merely “a retroprojection of later conflicts” onto the richly symbolic moment of birth. To Hausner, these were theoretical differences; he was focused on managing his clinic, and he instructed Sadská’s nurses to comfort patients in a “pediatric regression” by “stroking, taking a hand, etc.” — which required “a certain skill” in distinguishing regression from “adult manifestation on an erotic level.”

Havlíček argued that the psychedelic experience was essentially narcissistic and typically American — a retreat into a “luxurious uterus.”

The most fundamental dispute between the doctors, however, occurred over how LSD therapy should be conducted. In 1967, Grof got a fellowship to work at Baltimore’s Spring Grove State Hospital, which used “psychedelic” therapy, giving alcoholics one huge dose of LSD (400 µg or more) to induce a life-changing spiritual experience. Grof started thinking that Europe’s psycholytic advocates were on the wrong track: Repeated sessions of psychoanalysis were time-consuming and couldn’t grasp the profound sensations of ego death, rebirth, or cosmic unity that LSD patients often experienced at higher doses, which he saw could be beneficial. Havlíček had none of it: He argued that the psychedelic experience was essentially narcissistic and typically American — a retreat into a “luxurious uterus,” providing feelings of divine exaltation but socially worthless, separating the patient from the real world where their problems began, and where they had to learn to survive. Hausner, who’d been elected vice president of the European Association for Psycholytic Therapy, agreed: “In my experience,” he later wrote, “achieving true transcendental insight is rare unless the subject succeeds in discarding the negative aspects of his unconscious and erases the faulty programming that is causing the problem.” (To avoid confusion with psychedelic therapy, Hausner usually referred to the drugs as “psychodysleptics,” meaning that they induced a dreamlike state.)

Grof prepared a response, proposing a way to integrate psycholytic and psychedelic techniques at an international LSD congress to be held in Prague in September 1968, but the paper was never heard. On August 20, Soviet troops invaded Czechoslovakia to crush the democratic progress emerging during the Prague Spring. Then, on January 7, 1969, Havlíček died of leukemia. Sadská’s fortunes were destined to change after that.

When Hana K. arrived at Sadská in 1970, she spent four months in group therapy while Hausner assessed her. She answered questionnaires and wrote her autobiography, read books by Freud and Erich Fromm, and sat in on discussions about relationships — many of the patients were young and had family conflicts because the state wouldn’t assign them apartments of their own unless they were married. Then Hana started the LSD treatments, and by sharing work and experiences with other patients, for the first time in her life she made some friends.

After 22 sessions, Hausner decided that Hana had improved enough to join a group psycholytic session. Although his early research suggested that group LSD sessions had little value, Hausner found that low doses of the drug helped some patients see their own “faulty, unbalanced behavior” when interacting with others. Hana received 100 µg with half the patients in her group. At first, the experience was unpleasant, like she was being watched on a stage. But soon members of the community started violently arguing with each other — and Hana was flooded with empathy.

“I am actually beginning to understand and to relate to people,” Hana wrote in her diary. “I can see and understand the reason for the things they do, and I don’t hate them anymore! Poor doctor. He’s got so many children. How can he cope with it all?”

After the 1968 invasion, it took Czechoslovakia’s new Soviet-backed government several years to replace key officials with hardline communists, and during that time Hausner was able to continue LSD therapy. Newcomers joined Sadská, including a psychoanalyst from Poland and a group therapist from Barcelona, and foreigners continued to tour the clinic — R. A. Sandison visited in 1970 — but increasingly from the Soviet bloc, curious about methods unavailable in their own countries. “We have found your system of contacting LSD group’s therapy very fascinating,” two Polish psychologists wrote in Sadská’s guestbook after staying several weeks in the summer of 1969. “We have seen wonderful results. We have taken LSD ourselves and experienced that it helps very much in speeding up psychotherapy. We would like to arrange LSD group’s psychotherapy in Poland.”

To hear the people who worked there describe it, Sadská was more like an offbeat arts college than a Soviet medical facility. Hausner brought his three children to the clinic, and sculptors and dream interpreters came from Prague to give classes to the patients. Some evenings, they held masquerades or parties; the doctors and nurses and patients would dance together, and the next day, they would discuss in group how they had interacted. There were a few suicide attempts, but there were also romances: one older LSD patient, who had spent his youth in a Nazi concentration camp and suffered from depression, was so impressed by Sadská that after his discharge, he became a therapist at the clinic and married one of the psychiatrists. As one patient later wrote, “At Sadská, it was Freud and love.”

There were a few suicide attempts, but there were also romances.

Sadly, that love wasn’t felt in the Czech capital. Communists feared that the Western scourge of narcotics addiction was leaking into Czechoslovakia, and in December 1969, the popular magazine Květy ran an article about drug abuse by Prague youths, opening with a rumor that LSD could be bought in front of a downtown cinema from a car with Austrian license plates. Hausner increasingly had to defend the psychiatric use of LSD and the distribution scheme that he helped administer. At the prestigious Collegium Internationale Neuropsychopharmacologicum, held in Prague in 1970, he spoke on the “therapeutic and illegal use of Lysergamide”: After some 3,000 sessions with 300 patients at Sadská, he reported that general health improved for 60 percent of them, and life satisfaction increased for 70 percent. “Nobody of these 300 patients became habituated to LSD,” he asserted; distribution of the drug was under “rigorous governmental control,” and “no misuse has been observed.” But he was swimming against the tide. In February 1971, 34 countries adopted the UN Convention on Psychotropic Substances, classifying LSD as a drug of abuse with no therapeutic value. Czechoslovakia was only an observer of the proceedings, but the Soviet Union soon signed on, and Sadská came under scrutiny.

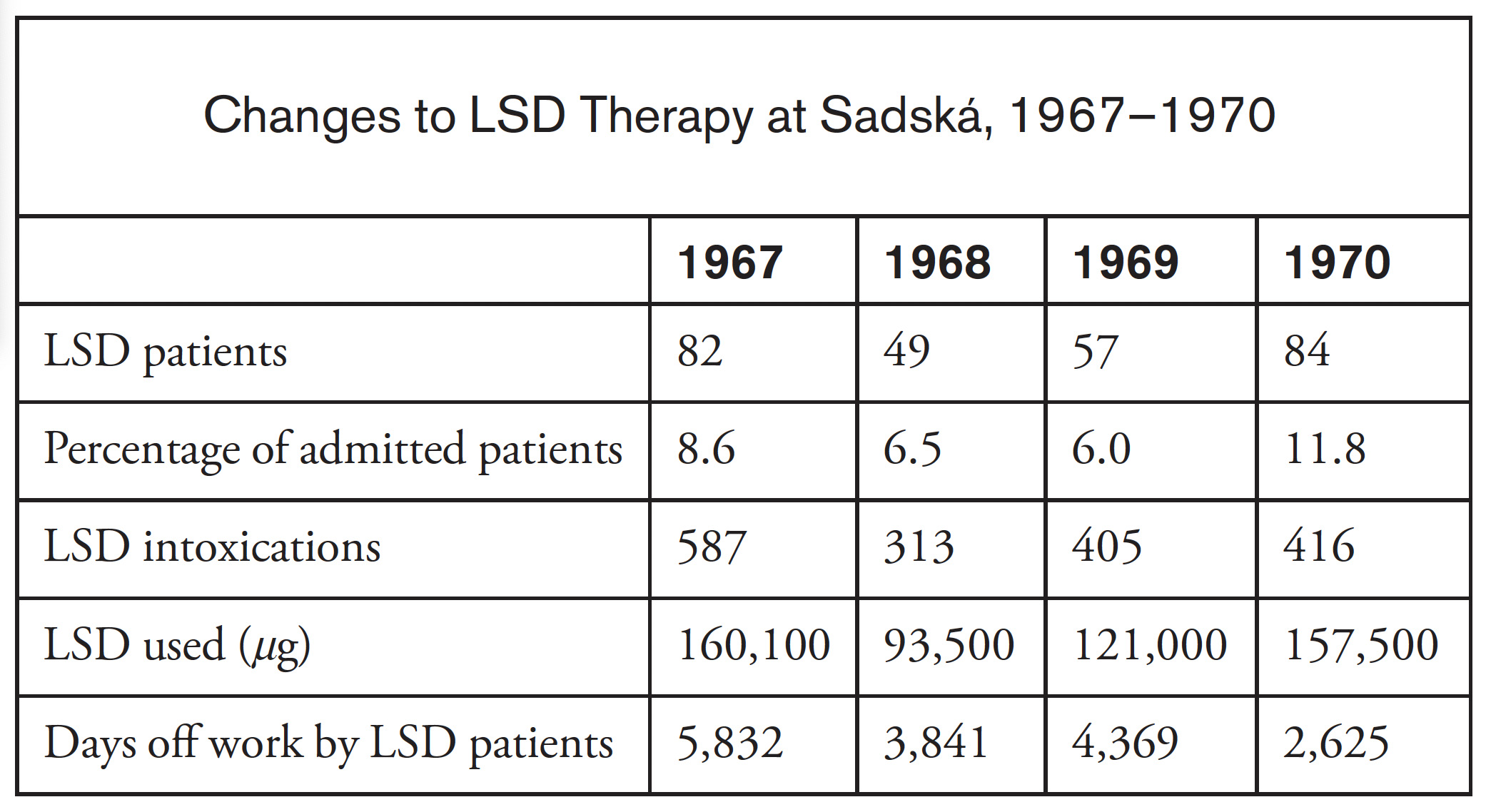

In May of that year, a panel of doctors conducted a comprehensive audit of the clinic “due to frequent negative comments” from the regional health authority. Hausner prepared a table showing that LSD patients were a small percentage of Sadská’s admissions, and the time they spent there was decreasing.

The panel commended Hausner for fulfilling the planned number of treatments, his focus on “modern currents” in psychiatry, such as “group psychotherapy and active pursuit of cooperation of the patient,” and his “progressive efforts” to reduce hospitalization via his “weekend” LSD therapy. But, “[a]s far as LSD treatment is concerned, we reiterate the fact that this method is not generally accepted. The number of patients treated in this way needs to be limited as much as possible, or to stay with LSD for a few cases that would only go to outpatient treatment.”

Every third or fourth weekend, about 40 patients would endure a “psycholytic marathon,” taking turns sitting for each other and heading back to work on Monday.

Hausner complied, increasingly putting new LSD patients on weekend therapy. Every third or fourth weekend, about 40 patients would endure a “psycholytic marathon,” taking turns sitting for each other and heading back to work on Monday. Each of them would have been hospitalized an average of 64 days without the program, Hausner calculated, so it saved the state 1.34 million Crowns per year. (At the time, the average salary in Czechoslovakia was 26,844 Crowns per year.) To save more money, Hausner recruited psychology students to assist on weekends, and many underwent a “training intoxication” with LSD for university credit.

Hausner continued to publish articles internationally, including one comparing the symbology of dreams to LSD hallucinations that was subsequently reprinted in a Czech journal for general practitioners. In March 1973, he chaired a conference on psychotherapy in socialist countries that was attended by experts from across the Soviet bloc — although he was careful to mention psycholytic therapy only once in his own paper, surveying the range of techniques used in Czechoslovakia at the time. (For example, Hausner, then president of the psychotherapeutic section of Czech Psychiatric Society, noted that 250 of its 300 members used hypnosis.) In June, he traveled to Oslo for the 9th International Congress of Psychotherapy, where he identified his practice as “dynamic confrontation therapy,” in which a patient faces the problems of past, present, and future (!) in a controlled environment, with psychodysleptic drugs targeting the “neurochemical, intrapsychic, interpersonal, psychosomatic and the valuation system area[s],” and ultimately providing a corrective emotional experience.

But officials back in Prague were likely suspicious of the relative freedom that Hausner enjoyed without a Communist Party membership. Drug abuse was becoming a problem in Czechoslovakia, and though nearly all the cases involved prescription medicines, often containing ephedrine or codeine, the bureaucrats feared that LSD was next. In October 1973, they inspected the Sadská clinic, and in its safe, they found 619 ampoules of LSD that had expired in 1969. In January 1974, they consulted the pharmacy that distributed the drug and learned it had another 2,400 ampoules that Hausner had ordered in 1971 and were about to expire. In a series of letters, Hausner apologized. Supplies from the factory had been unpredictable, he said, and LSD remained stable in glass ampoules for many years. Besides, the drug hadn’t been stolen or turned up on the black market, so what was the harm?

Hausner needed some good press, so he invited journalists from Květy to visit Sadská. The resulting article described a traumatized 18-year-old girl arriving at the clinic, and Hausner’s plans to treat her with LSD, accompanied by a full-page color photo of Hausner ministering to a female patient lying on a wildly patterned couch in his office under a wall of primitive masks. The deputy director of the regional health authority demanded that LSD therapy be stopped. Hausner apologized again, admitting the photo was “too provocative,” and he got letters from other doctors supporting the continued use of LSD. But the health authority ordered Hausner to send reports on every patient receiving the drug, and it started conducting spot checks of the clinic’s supply.

In the late summer of 1974, Hausner’s father died, and Hausner had a nervous breakdown. “He had the worst fears for the future, he was anxious about his family, and concerned about material security,” one of his colleagues later said. Hausner admitted that he’d considered suicide and was hospitalized in Prague for several months. The regional pharmacist came to Sadská, collected all the ampoules of LSD, and stomped on them in Hausner’s office.

“They took away all his appetite for work,” a nurse said years after this incident. Hausner suffered another breakdown and received treatments from his Prague colleagues that he’d tried to avoid in his own practice, including ECT, antidepressants, and lithium. When he finally returned to Sadská in 1975, he was emotionally flattened, a changed man. A nearby hospital took over administration of the Sadská clinic and converted the psychotherapeutic pavilion into a ward for chronic psychiatric patients. LSD was still theoretically available with permission from the health ministry, but nobody risked ordering it.

Hausner left Sadská in 1981, after he and Zdena divorced. Czechoslovakia drifted into a stultifying political “normalization,” and Hausner ended up in the industrial north, providing psychiatry to the employees of a uranium mine. When he died in 2000, Czech medical journals did not mention his passing.

For many decades, even after the communist regime fell in 1989, Czech medical authorities resisted any talk of reviving LSD therapy, and the few doctors interested in the drug were limited to conducting animal studies. But possibilities are beginning to reopen. Prague psychiatrists are studying the neurobiological effects of psilocybin — in a suite designed to resemble Hausner’s office as it appeared in Květy — and have established a private clinic offering ketamine-assisted psychotherapy, the first in central Europe, although such treatments are not yet covered by Czech medical insurance.

Hausner’s correspondence, patient files, and hundreds of pieces of artwork reside in the Czech Academy of Sciences archive, but they are currently inaccessible to the public. Thanks to the growing interest in psychedelics, a book that Hausner wrote in 1997 about psycholytic therapy at Sadská has finally been published, but to get a more complete picture of what happened at the clinic, I also sought out people who were there. Some 30 psychiatrists and psychologists worked or trained at the clinic; my colleagues and I interviewed nine of them, and while many said that Hausner was a superb administrator and psychiatrist, they also said that LSD didn’t “accelerate” psychotherapy because so much time was spent in sessions and analyzing the patients’ experiences. Several said that therapists were overwhelmed by the volume of material that LSD evoked and Hausner tried to do too much: Many of the LSD patients had neuroses or depression, but the conditions of others ranged from alcoholism to schizophrenia to psychopathy. I also interviewed five Sadská nurses, all of whom said that it was the most interesting period of their careers, and the clinic was “like a big family.” But did LSD therapy help the patients? “Well, they did not come back,” one nurse said. “They went back to life and everything was OK,” said another. “It is true that it was a half-year-long treatment. But it was successful, at least according to me.”

One woman said that she felt “broken” after every session and experienced unnerving flashbacks years later.

I also interviewed 15 former Sadská patients. Three said that psycholytic therapy hadn’t substantially changed their condition, and four said that it made their condition worse. One woman said that she felt “broken” after every session and experienced unnerving flashbacks years later. A man who suffered sexual neuroses said that he didn’t consider LSD useful because “it opened everything in allegorical terms” and confused the therapeutic relationship: In one session, he tried to rest his head in his doctor’s lap, and she rejected him, which took him a long time to overcome. But eight thought that Sadská’s therapy had helped. A woman who suffered from posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and sexual dysfunction said that she was “newly born” after her third session; she had been raised Catholic, and she said that LSD showed her “what belief really is.” A male alcoholic said that “LSD made the first step” to his sobriety and inspired him to become a therapist for other alcoholics.

Hana K. was discharged not long after her group LSD session. In 1972, she married a fellow Sadská patient, and eventually they had two sons. Today, she says that she’s become happier as she gets older, and the worst time of her life was just before she went to Sadská.

“A home, and kind people around me, that is something I never had before,” she said of the clinic nearly 50 years later. “And with LSD they taught me things I never came across anywhere else. But whether the treatment would be equally as successful without LSD I cannot say.”

Ross Crockford is an award-winning journalist based on Vancouver Island who has written about the medical use of psychedelic drugs for publications in Europe and North America. He is currently preparing a book about the history of LSD in communist Czechoslovakia. A version of this article with a complete list of notes and resources can be downloaded here. This story was excerpted from the volume “Expanding Mindscapes.”

This article was originally published on MIT Press Reader.