“Jumping genes”: A new model of Alzheimer’s

- For years, Alzheimer’s was believed to be caused by a build-up of misfolded proteins. However, drugs that clear out these proteins have little to no effect on the disease.

- This has caused scientists to seek other explanations for Alzheimer’s, such as inflammation, immune system dysfunction, and metabolic dysfunction.

- A new hypothesis suggests that the disease is the result of “jumping genes” in the brain.

The causes of Alzheimer’s Disease are complex and mysterious. Alzheimer’s is characterized by the build-up of plaques and tangles, consisting of insoluble amyloid and tau proteins, respectively, in the brain tissue, and for decades it was widely believed that plaques are the culprit.

Pharmaceutical companies have developed hundreds of drugs that remove plaques or prevent their build-up, but although many of these alleviate Alzheimer’s-like symptoms in mice, they invariably fail in human clinical trials or have only modest effects. These failures have led researchers to investigate other possible causes, including inflammation, immune system dysfunction, and metabolic dysfunction. More recently, evidence that “jumping genes” may play a role has emerged.

Jumping genes

“Jumping genes” (more formally known as transposable elements or transposons) are DNA sequences that can move from one location of the genome to another. They exist in various forms, including as remnants of ancient retroviruses, and make up about 45% of the human genome. When activated, the movements of this genetic “dark matter” can delete, duplicate, or otherwise rearrange chromosomes and alter gene activity.

The discovery in 2018 that tau protein activates jumping genes in the human brain raised interest in the idea that DNA transposition may contribute to Alzheimer’s. Since then, more evidence that jumping genes contribute to Alzheimer’s has emerged. For example, retrovirus-type jumping genes are more abundant in postmortem human brain tissue obtained from Alzheimer’s disease patients than in tissue from healthy controls, and these same jumping genes promote nerve cell death in fruit flies.

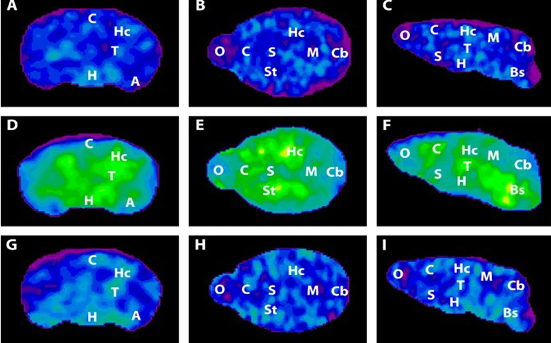

A small study of 25 patients, published in 2022, shows that onset of Alzheimer’s is preceded by a transposon “storm,” with increased or decreased activity in 1,790 different retroviral jumping genes. In mice, these jumping genes cause nerve cell degeneration by activating immune system receptors. Other research shows that activation of these endogenous retroviruses during normal brain development induces an inflammatory response, and that tau protein accelerates jumping gene activation in the mouse brain.

A new model of Alzheimer’s

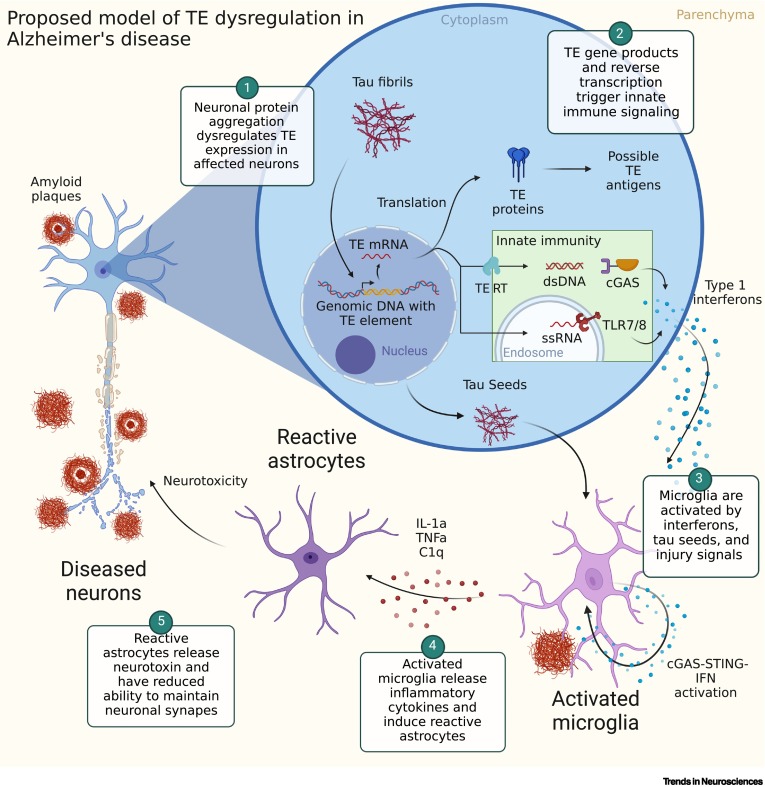

These and other findings have led researchers to propose a preliminary model of how jumping genes might contribute to Alzheimer’s Disease.

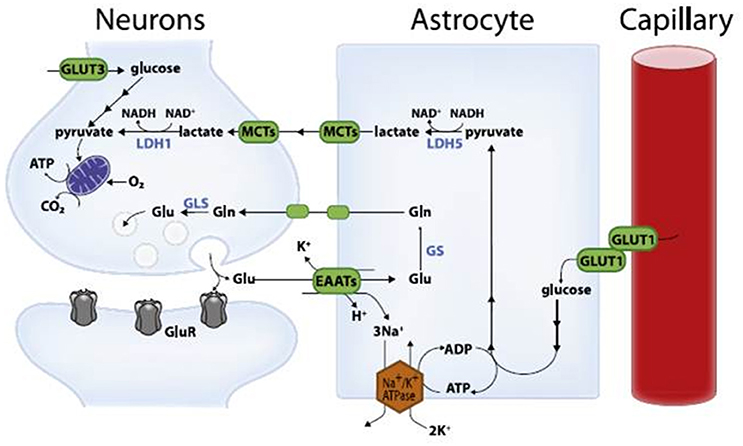

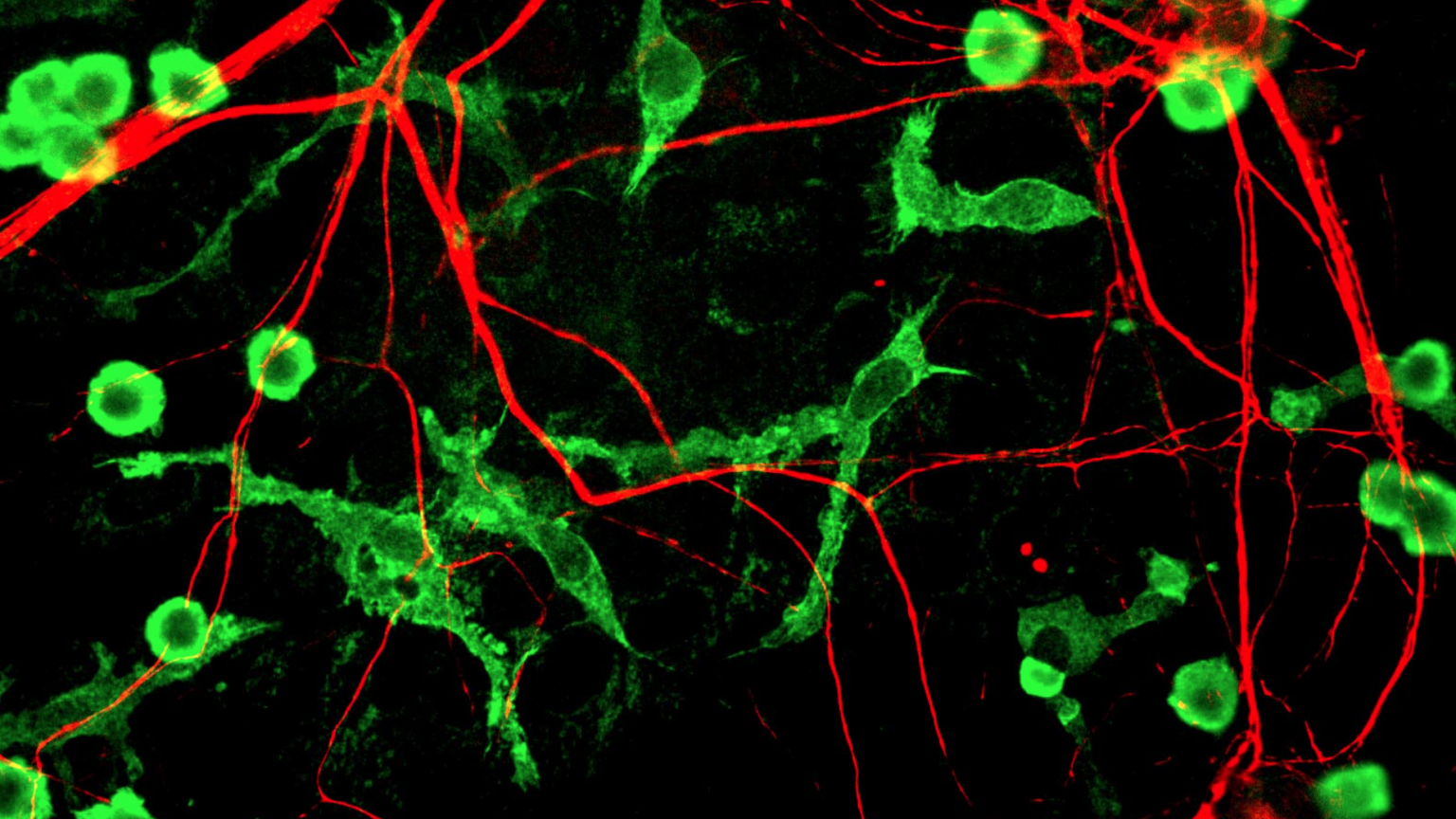

According to this model, aggregation of toxic tau protein alters jumping gene activity, leading to the synthesis of proteins that trigger an inflammatory response. Microglia, the brain’s immune cells, then react to this by releasing chemicals that promote further inflammation and interfere with synaptic function, leading, possibly, to nerve cell degeneration and death.

This is a new area of research which raises more questions than it answers. But the availability of new techniques such as single-cell transcriptomics now enables researchers to perform increasingly detailed analyses, and will help them identify exactly which jumping genes are altered and in which regions, or cell populations, in the brain.

Future work could provide important insights into the mechanisms of neurodegeneration in Alzheimer’s and other diseases. It could also identify biomarkers for these conditions, and novel drug targets for their treatment.