Meet the neuroscientist who uses puzzles to help the brain heal after injury

- Solving simple puzzles can help to “rewire” the brain, and it may even help to repair damage caused by traumatic injuries.

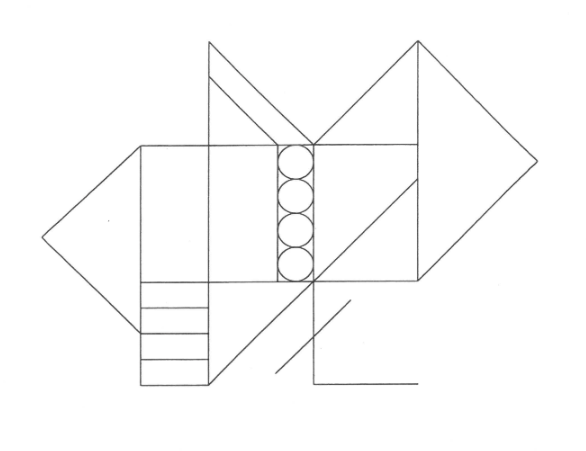

- By working with abstract illustrations, people can activate long-dormant parts of their brains.

- According to some psychologists, brain puzzles can also help elite performers, from athletes to scientists, to up their games.

When neuroscientist Donalee Markus first meets with her clients, she asks them to reproduce an abstract image using colored pencils. Every minute or so, they are asked to change pencils, from red to green to blue, and then other colors if necessary.

The colors leave behind traces of their problem-solving strategies. Do they begin by drawing the square at the center of the image? Or moving from left to right? Or recreating the pointed figures on the outside? Or isolating the small details in the center of the image?

For four decades, Markus has offered therapy and training for victims of traumatic injuries, people struggling with developmental and emotional problems like autism, and high-achieving processionals.

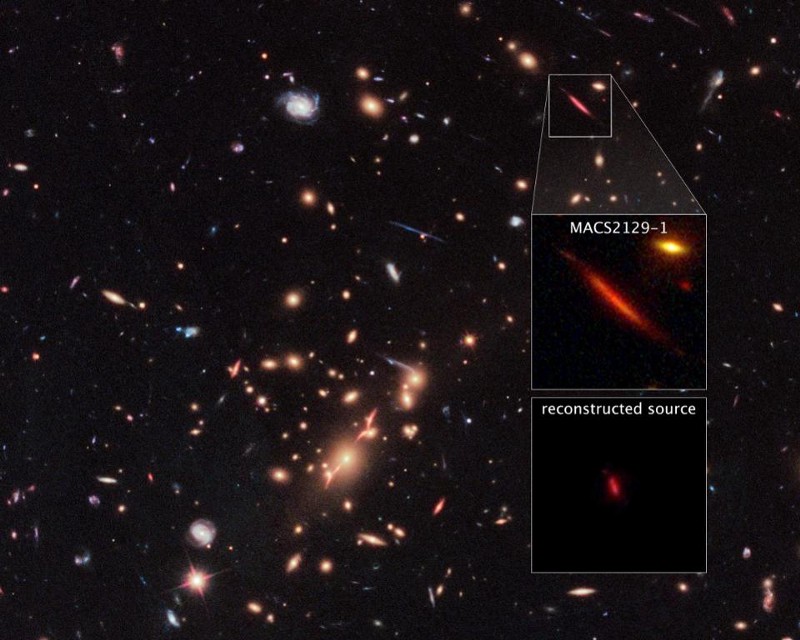

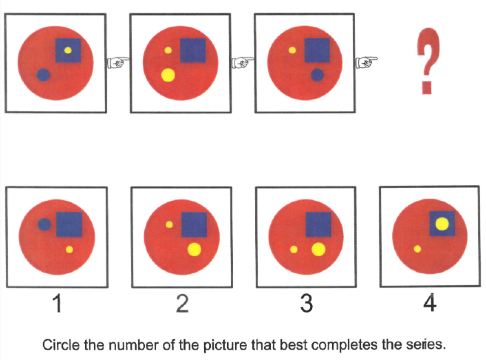

As the work continues, clients work with a dizzying array of abstract images, drawn from a library of 18,000 images. They learn to compare images by isolating and analyzing their parts, one by one. Which parts got bigger or smaller, moved or changed angles, altered shapes or color or density?

It sounds simple, except that people have wired their brains to pay more attention to some elements than others. For patients with traumatic brain injury, the process can be physically and emotionally taxing.

Why puzzles might be therapeutic

These puzzles can be found on apps for phones and tablets and in books and printouts. Whether they’re high-tech or low, the process is the same: Use puzzles to identify which neural pathways people use to process the world and which grooves are underdeveloped. The clients then work with puzzles they find difficult in order to “rewire” the brain — or, form new neural pathways through neuroplasticity — and increase its capacity to perform a wide range of tasks, from walking to organizing to high-level thinking.

Picture puzzles combine two powerful agents of brain change: images and challenges. Vision dominates the sensory activities of the cerebral cortex, the so-called “executive” region of the brain. A 2002 study by David Van Essen of the Washington University School of Medicine found that “cortex that is predominantly visual in function occupies about 27% of the total extent of cerebral cortex [compared to] about 8% of cortex [that] is predominantly auditory, 7% somatosensory, and 7% motor.” The rest, about 51 percent, “includes major domains associated with cognition, emotion, and language.”

Images, as research shows, can trigger specific types of brain activity in a variety of ways. A 2001 study in Neurolmage, for example, found that viewing two similar sets of images lit up the brain in different ways. Artistic images lit up the parts of the brain processing value and reward, while more pedestrian images engaged the part of the brain for simple recognition.

The other element of brain change is the deliberate effort required to perform a task. Wordle and Soduku fans might be disappointed to learn that games themselves do not necessarily rewire the brain. “If you do Sudoku puzzles or crosswords, all that you get better at is Sudoku puzzles and crosswords,” neuroscientist Daniel Levitan notes.

Anders Ericsson, the Conradi Eminent Scholar of Psychology at Florida State University, coined the term “deliberate practice” to describe activity that requires intense effort, concentration, and strategy. Deliberate practice, he says, “entails considerable, specific, and sustained efforts to do something you can’t do well—or even at all.” Engaging in difficult tasks with focus and extended effort–like solving picture puzzles–can rewire the brain. But it’s not easy; it requires discipline and commitment.

Other researchers, doctors, and therapists have used pictures in their work. So what’s different?

“What I’ve done is create instruments, hierarchically organized, with multiple variables,” Markus says. “They get harder as you go and use different logic [and] analogies.”

Selected and sequenced well, these instruments may provide a useful treatment for a wide range of physical and mental ailments.

The challenge lies in learning to solve problems in new ways. Over the years, Markus has identified eight basic approaches to processing information and solving problems: “bottom-liner,” “left-to-righter,” “direction changer,” “central shaper,” “outliner,” “disconnector,” and “random connector.” They vary according to whether they start with the familiar or explore openly, seek guarantees or embrace risk, are emotionally engaged or not, and are result-oriented or see possibilities.

The clients

At her fashionable home in Highland Park, Illinois, Markus and her team of eye specialists and psychologists work with children diagnosed with autism, victims of traumatic injuries, and others suffering for reasons they cannot pinpoint. The clients struggle with symptoms like dizziness, loss of balance, nausea, blurred vision, and headaches. Some have been driven to the edge of suicide by their conditions.

Her clients also include super achievers in business and science. For years Markus worked with NASA. She coaches athletes, performers, and business tycoons. The comprehensive guide to her approach, Restructuring Your Business Brain, is targeted at elite performers.

A puzzle can take one person a minute and another an hour — not because of intelligence, but because of wiring. “However accomplished they are, most people are missing something,” Markus says. But as they work on the puzzles, once-impossible tasks become easy — and they scale up and work on tougher and tougher puzzles.

For those who stay, improvement comes in life-changing bursts. By activating their whole brain, they not only think better and regain control of their body. They also become more present and empathetic. Families comment on their greater patience and problem-solving skills.

Using pictures for therapy got a surge of attention in 2011 when a computer science professor named Clark Elliott published his memoir The Ghost in My Brain. For eight years after a 1999 car crash, Elliott met with dozens of specialists. Nothing alleviated his symptoms. A single father, he could not afford to stop working. Every day, he spent hours making a trip from the parking garage to his classroom at DePaul University. He shuttled along the concrete ground, holding the walls, inching forward as his head spun and nausea wracked his body. Finally, someone told him about Markus and her unusual form of picture therapy. Within 10 days of hard work, he started to get back to normal.

Elliott quotes Markus at length in his 2017 article in Functional Neurology, Rehabilitation, and Ergonomics: “When he had mastered the simplest shapes such as triangles and squares, we gradually added complexity: overlapping shapes, multiple instances of shapes on a page, 2D shapes, 3D shapes, symmetrical and asymmetrical shapes mixed together, and so on. Because Clark was a high-functioning individual we also had him rehearse complex images and rotations that overlapped.”

Elliott’s story is an inspiring tale of grit, striving, and overcoming. But his book also speaks to readers who wanted to activate brain processes that they had underused over the years. Markus calls her method “brain restructuring.” Back in the 1970s, few believed that the brain was plastic or malleable enough to be altered or improved. But the science has proven that almost anyone can engage in deliberate exercise to arouse the brain’s underused neural pathways.

When her four-year-old son was diagnosed with autism, Neha Pandey responded like the scientists she is. She tested a wide range of treatments: biomagnetism, photobiomodulation, homeopathy, grounding mats, and diet. When they met Markus, they noticed improvement—and motivation on her son’s part. “Treatment just started but his cognition has improved,” she said. He is devouring the puzzles—some used with NASA scientists. “I have to say, ‘That’s enough for now,’” Pandey says. “For the first time he became comfortable with someone else,” she said.

Amy Roberts-Brubaker, a 50-year-old pharma salesperson, remembers her first visit. After Markus pulled out puzzles, Roberts-Brubaker resisted. “Oh, I don’t do geometry,” she said. Markus laughed and directed her to find angles. She couldn’t. “Sure, you can,” Markus said, as she showed how to isolate parts of the image. Roberts-Brubaker’s first homework puzzle took an hour. “I noticed quickly that I loved black-and-white but didn’t like color,” she said. She did not see yellow dots that were right under her nose. The experience “was making my ears ring.” These experiences helped Markus identify which picture puzzles could help activate dormant parts of her brain.

Markus has also brought her system to the leadership training program at NASA. For Christine Williams, who coordinated the program, the process provided game-like feedback that transformed her work. “I can see my progress, how I first struggled and then I’m like, ‘OK, I’ve got that now. What’s the next level?’” As she worked with the puzzles, she says she developed a more sophisticated way of mapping organizational challenges and working with colleagues.

Williams marvels at Markus’s ability to observe and direct clients. “She’s watching everything about you—where you hold your breath, how you move your eyes, where you’re having difficulty,” she said. “She has a phenomenal sense of everything that’s going on in this moment. She’s able to pick up on all those little nuances.”

The mentor

Donalee Markus’s journey began in the 1970s. Working on her Ph.D. in Education Administration and Policy Studies at Northwestern University, she worked with Reuven Feuerstein, a protégé of the developmental psychologist Jean Piaget who ran a program for psychological services for immigrant children in Israel. Many children tested low on intelligence tests but showed remarkable gains when they got individual attention.

Using a “mediated learning experience”— working directly with a student to identify strengths and weaknesses — Feuerstein guided learners “through the backwaters of their own subconscious thought processes.” The goal was to jolt them out of familiar, comfortable grooves. Working one-on-one limited the number of clients he could help. But Feuerstein and Markus developed abstract pictures that could also arouse the underused parts of the brain.

Pictures work because the brain experiences the world more visually than any other way. Even blind people experience the world through their mental images, maps, and models. When working one-on-one, Markus works with an eye expert named Deborah Zelinsky of the Mind-Eye Institute. Patients are fitted with glasses that reorient what and how they see. That experience can be as painful and disorienting as doing puzzles. But it is critical in reshaping the brain.

“As a species we are primarily visual/spatial entities to the very core of our being,” Clarke Elliott noted in an email. “The symbols of human thought itself are constructed and manipulated through this kind of processing, and of course such processing drives language, emotion, planning, balance coordination, motor coordination, [and] our sense of ourselves in the world.” In fact, as Elliott notes, “retinas are actually brain matter that happens to be hanging out the front of our face.” How better to reshape the brain than by manipulating its external piece?

Working with Markus does not come cheap: She charges $375 an hour (the fee includes 200 to 250 pages of pencil-and-paper exercises), which isn’t covered by insurance. Using her other learning tools, individuals can work through the same exercises. “It’s the same experience, it’s just not intensified,” she said. Without mediation—the expert’s guidance—the process could take longer and hit some dead ends. But it still rewires the brain.

Is the mediation of an expert like Markus necessary? For treating serious injuries and ailments, yes. Other learners—people who simply want to use all of their brain and get out of familiar grooves—might only need access to the puzzles and a guide to using those puzzles strategically.

Like other pioneers, Markus remains outside the fraternity of specialists and technocrats. Despite a healthy collection of case studies attesting to the effectiveness of her approach, she has never had a classic double-blind, longitudinal study. So, even though the case studies are impressive, it’s hard to pin down the exact efficacy of the approach. She works mostly outside the normal channels of care for traumatic injuries, autism, and other brain-related dysfunction.

At 78, Markus resists the idea that she should work more with the medical establishment. Pointing to her 2007 article in Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Clinics of North America, she asks, “How many letters and comments do you think I got for that? None, that’s how many.” Working with the establishment, she said, is like getting on a treadmill to nowhere. “If someone wants to get a grant, that would be great,” she says. “But I have apps to write and people to work with. I don’t have time.”

If people want to rewire their brains with pictures, might there be a midpoint between her hands-on work and the individual use of puzzles in books and apps? What about small-group work? Markus can imagine groups getting together to apply her methods without her direct oversight. She applauds the “spark groups” formed after Harvard neuroscientist John Ratey showed how play improves the brain’s capacity to learn. Years ago, her program was used at Encyclopedia Britannica’s after-school centers in Highland Park. “But they said they couldn’t get someone for $15 an hour to run the program,” she said.

No one knows what will happen when Markus, nearing 80, finally retires. But she has one certain legacy: her 18,000 instruments and the gratitude of people whose lives were changed by working with pictures.

Sidebar

Donalee Markus is part of a growing movement to promote mental and physical growth and healing. Wim Hof trains people to engage in deep breathing and immersion in ice-cold water to learn how to master their minds and bodies. The fasting movement uses time away from eating to force the body to respond to a mini-food emergency.

Over a sustained period, strain and discomfort can contribute to disease, as figures like the late back specialist John Sarno and the trauma expert Gabor Mate show. In a 2002 article in the journal Pediatrics, for example, Jack P. Shonkoff of the Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University and his colleagues noted that early childhood stress “can damage the developing brain and other organ systems and lead to lifelong problems in learning and social relationships as well as increased susceptibility to illness.” Studies show a correlation between trauma and higher rates of cancer, Epstein-Barr virus, and overall immune functioning. Addressing the source of the pain may be the key to healing.

Still, while ongoing struggles with stress can be damaging, strain is essential to neuroplasticity. When struggling with solving a picture puzzle, it’s understandable to feel frustrated or even stupid. But Markus teaches a strategy to overcome the discomfort. Break the picture into pieces. Identify similar shapes. Notice changes in the size, location, angles, or color of a piece of the puzzle. These actions prove difficult when the brain is not used to doing it—not because of intelligence.

Take it a step further. Working with puzzles not only promotes brain development but also creative processes. In the latter half of the 20th century, a Soviet scientist named Genrich Altshuller developed a process called TRIZ for solving technical problems and inventing new tools and processes. Alfred Hitchcock regularly carried a book called Plotto to help him write scenes. These kinds of prompts guide learners and creators, deliberately, to explore aspects of issues they might otherwise ignore. The goal is not to find a simple answer to problems but to provide a process for deliberately addressing those problems.