Instant gratification: The neuroscience of impulse buying

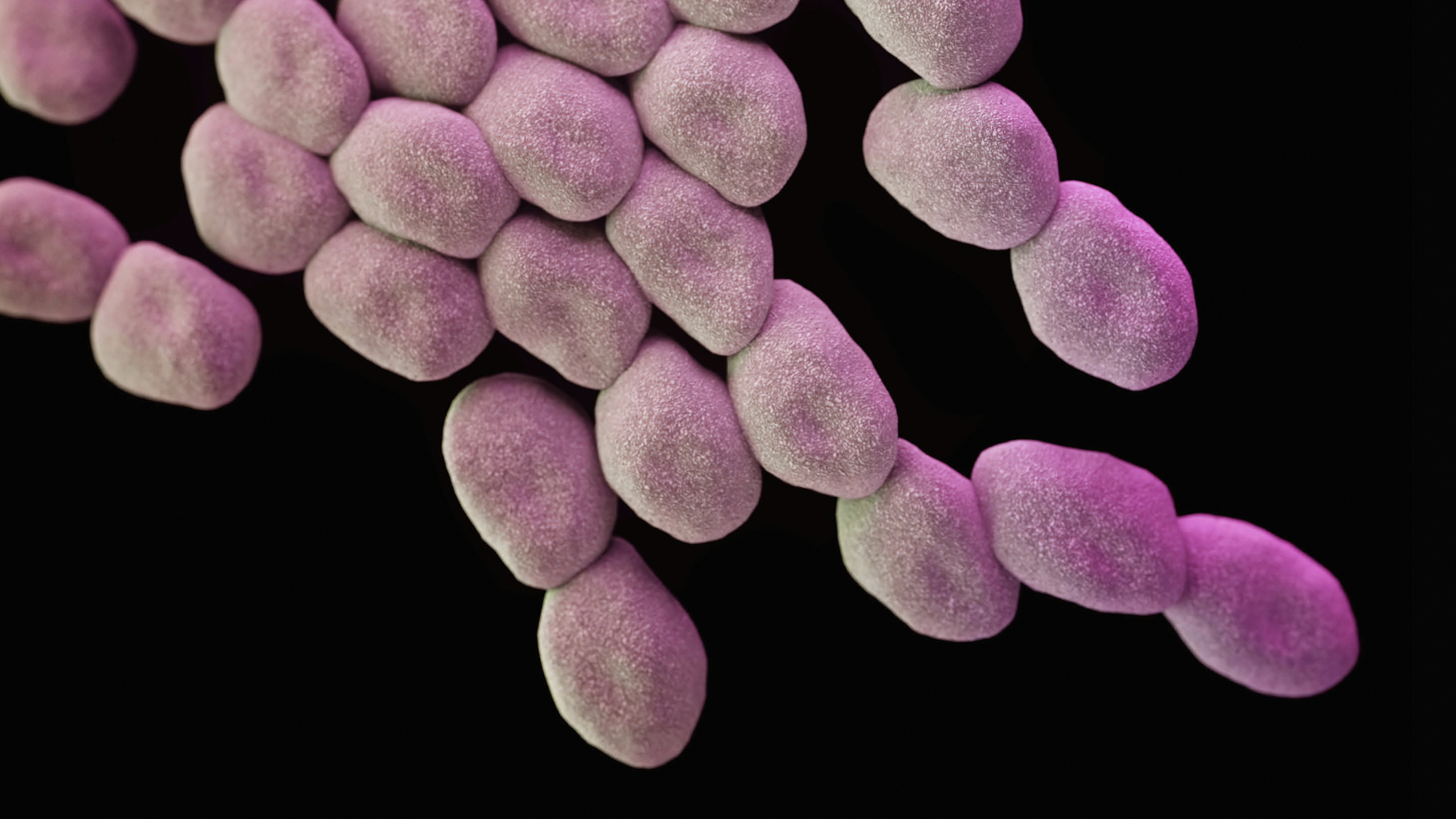

Ibravery via Adobe Stock

- A recent episode of “Your Brain on Money” explored the psychological factors behind impulse buying.

- Online shopping has made it harder than ever to resist impulsive purchases, which may provide instant gratification but not long-lasting happiness.

- Some strategies for resisting impulse buying include planning your shopping and being cognizant of how retailers manipulate consumers.

It’s arguably never been harder to resist impulse buying. Online stores have taken the sales tactics of brick-and-mortar stores to new manipulative heights, barraging browsers with an arsenal of psychological tactics to get you to spend as much money as possible. Odds are you have encountered these tricks — or “dark patterns” — as the user-experience consultant Harry Brignull dubbed them in 2010.

A 2019 study from researchers at Princeton University catalogued some of the most common dark patterns, like urgency, which might show you a countdown timer warning that a (supposedly) special offer is going to end in 60 seconds. There’s also “confirmshaming,” which makes you click a box like, “No thanks, I’d rather pay full price!” when you decline to sign up for a store’s rewards program. And social proof tactics inform you that “Alexandra from Anaheim” just saved hundreds of dollars on her purchase. (Spoiler: Alexandra doesn’t exist.)

That is not to say that it is any easier to avoid an impulsive purchase in the store. In some cases, shoppers may be more likely to spend impulsively in physical stores because of “the senses’ capacity to generate a sudden response, and it has a strong hedonic component, which leads to a decision without further deliberation,” research suggests.

The same study found that more than 25 percent of consumers consider themselves compulsive shoppers. Compulsive shopping, known as “oniomania,” was first described in the early 1900s by the German psychiatrist Emil Kraepelin. Around that time, many people still believed in the concept of Homo economicus — a 19th-century idea that viewed people as rational decision-makers who always act in their own self-interest.

Today, Homo economicus is extinct: Decades of psychological and economic research has shown that what often drives our spending behavior is not rationality but emotionality.

“The human brain is not a thinking machine that feels. It’s a feeling machine that thinks,” Terry Wu, a neuroscientist and business consultant, told Big Think. “Humans have this innate desire to seize a sense of control. Driven by our strong emotions, we stop making rational decisions when it comes to buying.”

The psychology behind impulse buying

Under what circumstances are you most likely to spend money on something you don’t need? Chances are it is when you are stressed out. Stress can cause people to feel that they do not have control over their environment, and one way to regain control is to allocate money in strategic ways. One is through spending.

A 2016 study found that people are more likely to spend money when they are stressed out. Stress triggers the release of cortisol, a hormone that helps us respond quickly and effectively to threats in our environment. In the modern and developed world, the stressors we face often are not physical but psychological, and businesses capitalize on this.

“Behavioral responses to stress in our modern environment — replete with conveniences such as big box stores and restaurants — do not necessarily affect one’s ability to stay alive versus face death,” the 2016 study noted. “However, performing strategic behaviors in response to stress may help an individual function in day-to-day life.”

Why stores run out of toilet paper

Impulse buying can occur especially for items perceived as necessary. This spending behavior “provides a sense of control because it makes products that are useful for one’s daily survival readily available,” the study noted. A recent example of this phenomenon is the massive amount of spending on toilet paper during the pandemic.

“Toilet paper hoarding had nothing to do with fighting the virus,” Wu told Big Think. “It was really about people gaining a sense of control in an attempt to lower anxiety and stress.”

Stress can also cause us to spend more on unnecessary things, partly because we are not always good judges of what we really need. The 2016 study noted that “spending on nonnecessities, like designer clothes, may occur because the nature of the stressor has led consumers to perceive such products as necessities.”

Savvy marketers can make unnecessary items seem necessary by promising to fulfill deep-seated psychological needs with products: Feeling insecure? Read this self-help book and turn your life around. Don’t like the way you look? Buy this $180 pair of sneakers. Want more friends? Drink that new tequila in the commercial with all the smiling, good-looking people.

Instant gratification

Our desire to gain control over our environment is not the only psychological factor that nudges us toward impulse buying. There is also the problem of instant gratification. When we are feeling stressed, tired, or anxious, it is more difficult to make thoughtful decisions using the rational part of the brain, the prefrontal cortex. Often, emotions take over via the limbic system.

Shopping offers an easy way to get a hit of dopamine — and thus feel immediately gratified — when we are stressed out. Online shopping is a bit strange in terms of instant gratification; the research on it is a bit sparse compared to in-store shopping, but it seems to create two points of gratification: one when you click “buy” and another (more delayed point) when the item actually arrives.

In any case, the gratification you get from buying things is likely to be short-lived. Sure, some products may yield some form of long-lasting happiness; these are likely to be products that produce enjoyable and repeatable experiences, like a bicycle that lasts years or a good book that you read a few times. But most products quickly lose their ability to gratify. That’s especially true for people with compulsive buying habits, many of whom “rarely or never” use the stuff they buy, according to a 2015 review.

How to avoid impulse buying

The instant gratification of shopping combined with the delayed pain of spending on credit can lead to bad spending habits. And these habits can become even more destructive when we get stressed out. That is why it is helpful to be cognizant of your spending behaviors and to set up barriers between yourself and retailers.

One strategy is to plan your shopping in advance. Terry Wu often asks consumers, “The last time you shopped on Amazon, did you decide what to purchase or did Amazon decide for you before you even came to the website?” Just as people leave the grocery store with more than they planned to buy, many of the online purchases we make were unplanned. By making a shopping list ahead of time, you are more likely to shop with the rational part of your brain and less likely to succumb to impulse purchases.

Planning is not just about what to shop for, but also when. Wu noted that the ability to shop 24-7 is a modern invention; in the past, people tended to dedicate one day of the week to shopping. So one strategy is to allow yourself to shop only for an hour or two on certain days each week. You can make this easier by removing shopping apps from your devices.

Exercising is another way to dispel impulsive urges. Physical exercise not only releases the same types of feel-good neurotransmitters you get through shopping but also decreases stress and anxiety, which can lead to impulsive spending behaviors.

“Another way to reduce your stress is to seek social support,” Wu told Big Think. “When you’re connected with other people, you gain a sense of safety. That sense of safety can blunt your stress response and make your frontal cortex function better.”

As online shopping becomes more ubiquitous and frictionless, it is unclear how consumers will adapt their spending behaviors. The deck seems stacked in favor of online retailers: Gone are the salespeople, but in their place lie virtual traps coded to exploit our least rational tendencies. So even if “Alexandra from Anaheim” saved $200 through that soon-to-expire special offer, remember you don’t have to.