Why do animals play? The answer is more complex than you think.

Anyone who has ever chucked a tennis ball in the general vicinity of a border collie knows that some animals take play very seriously. The intense stare, the tremble of anticipation, the apparent joy with every bounce, all in pursuit of inedible prey that tastes like the backyard. Dogs are far from the only animals that devote considerable time and energy to play. Juvenile wasps wrestle with hive mates, otters toss rocks between their paws, and human children around the world go to great lengths to avoid make-believe lava on the living room floor.

When a dog chases a ball or a child adjudicates relationship disputes in doll-land, something important and meaningful is clearly happening in their minds, says Laura Schulz, a cognitive scientist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge. “Play has a lot of peculiar and fascinating properties,” she says. “It’s totally fundamental to learning and human intelligence.”

Scientists take play seriously, too. For decades, psychologists, evolutionary biologists and animal behaviorists, among others, have labored to understand the playful mind. They have given toys to octopuses, set up wrestling matches for rats, trained cameras on wild monkeys in the jungle and on semi-domesticated children on the playground. Their biggest question: What do these creatures get out of playtime? Clarifying the motivations and benefits of play could tell us much about behavior and cognitive development in people and other animals, Schulz says.

Answering this question, however, has proved surprisingly difficult. Some of the most obvious explanations haven’t held up to scientific scrutiny.

One hypothesis, for instance, is that play helps animals learn important skills. But experiments haven’t borne this out. A 2020 study of Asian small-clawed otters living in zoos and wildlife centers found that the most dedicated rock jugglers weren’t any better than their non-juggling friends at solving food puzzles that tested their dexterity, like extracting treats jammed inside a tennis ball or under a screw-top lid.

Researchers were surprised, but the otters were following a long-standing tradition of animals that don’t seem to learn much through play. Previous studies had found that kittens that grow up surrounded by cat toys aren’t especially successful hunters as adults, and playful juvenile meerkats aren’t any better as adults at managing territorial disputes.

As Schulz and a colleague write in the Annual Review of Developmental Psychology, even human children, arguably the most playful creatures in the world, don’t seem to reap any definitive long-term emotional or developmental benefits from pretend play, an elaborate and well-studied form of human play. Whether studies look at creativity, intelligence or emotional control, the benefits of play remain elusive. “You can’t say that kids who play more are smarter or that kids who engage in more pretend play do better,” Schulz says. “None of that is true.”

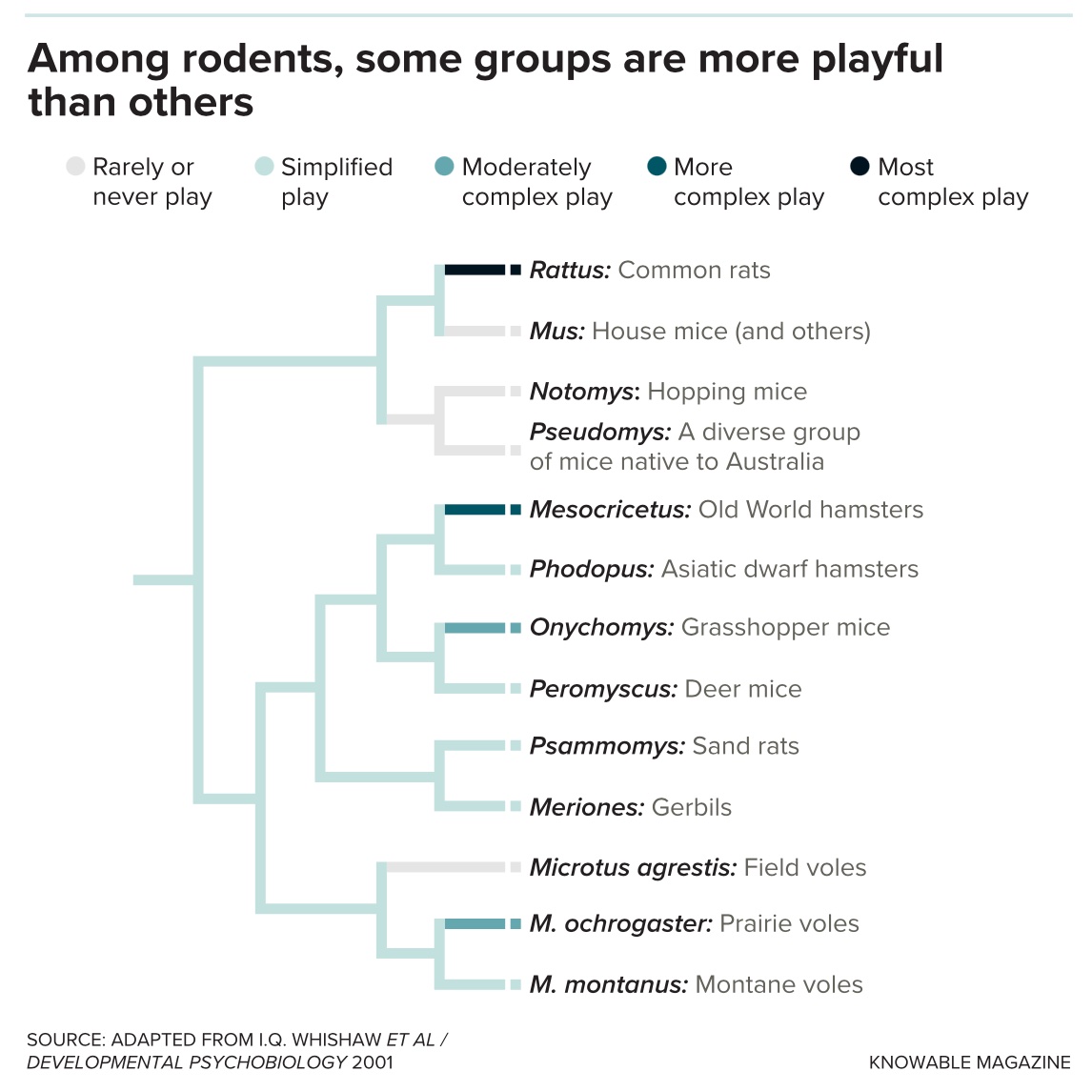

Play is actually somewhat rare in the animal world — you’re unlikely to run across a playful rattlesnake, a recreating eagle or a whimsical bullfrog — which only deepens the mystery of why it exists at all, says Sergio Pellis, a behavioral neuroscientist at the University of Lethbridge in Alberta, Canada, and coauthor of a 2010 book, The Playful Brain. Evolution normally encourages behaviors that help a species survive and propagate. It doesn’t favor fun for fun’s sake. Play “isn’t like eating or sex,” Pellis says. “We have to explain why it shows up in some lineages but not others.”

Playfulness is also highly individual, giving scientists the chance to compare playful otters, kittens and meerkats with their more businesslike peers, says Jean-Baptiste Leca, a cultural primatologist and a colleague of Pellis at the University of Lethbridge. Leca has spent much of his career studying macaque monkeys that play with rocks in the jungles of Bali and the forests of Japan. They clack rocks together and move them around, scratching the ground. (Tourists often wonder if the monkeys are trying to write, but they aren’t there yet.)

Some macaques really embrace the hard-rock lifestyle, which Leca sees as an important personality trait. “Twenty-five years ago, saying that animals had personalities was almost taboo,” he says. Now the idea is more accepted. “Animals vary a lot in their boldness and their willingness to try new experiences.” So far, he has seen no evidence that playing with rocks helps macaques learn to put rocks to a practical use, such as cracking open tough nuts. Anecdotally, he’s seen some especially playful young monkeys become the leaders of their troops, but it’s unclear if having rock-playing on their resumes had any bearing on their promotion.

Children, of course, have personality for miles, and there’s no doubt that some kids are more playful than others. But there’s still no clear connection between playfulness and overall abilities, says Angeline Lillard, a psychologist at the University of Virginia. Lillard and colleagues reviewed the state of the science on pretend play and cognitive development in a 2013 report in Psychological Bulletin. Whether studies looked at problem-solving, creativity, intelligence or social skills, there was no consistent sign that playful children had any advantages. “People will say, absolutely, pretend play helps development, but we couldn’t find any good evidence,” says Lillard. To her mind, subsequent studies have failed to clarify the picture.

So, if play isn’t making animals smarter and honing their life skills, what can it possibly be good for? Its purpose must be more subtle and perhaps more fundamental than once thought, Pellis says. Play may not enhance easy-to-measure things like IQ, but it may prime the brain to cope with the challenges and uncertainties of life. Consider rats, some of the most play-hungry animals on the planet. When young rats wrestle and run around, Pellis says, they’re testing boundaries and exploring new possibilities. What happens when I jam my snout in that other guy’s neck? Will he chase me if I run? How hard can I nip at him without getting attacked?

Those lessons matter. Studies by Pellis and others have found that young rats deprived of playmates grow up with less-developed prefrontal cortexes, a part of the brain deeply involved in social interactions and decision-making. These animals also tend to suffer deficits in short term memory, impulse control and the ability to notice or react to threatening gestures from other rats. “If you don’t have play experience with peers, you’re not as good at fighting, you’re not as good at having sex, and you’re not as good at coping with a novel environment that you haven’t encountered before,” Pellis says.

Pellis suspects it doesn’t take a lot of play to prevent these deficits. Studies with rats, ground squirrels and other rodents suggest that young animals need to experience only a little play to have a fully formed prefrontal cortex, comparable to those of their more playful peers. After that threshold is reached, it really does seem to be all fun and games.

Another possible explanation for play, says Leca, is that it’s an evolutionary byproduct. He notes that many animals, especially young ones, have an innate need to explore and experiment, a trait that could be useful for discovering food sources or learning other important lessons. This thirst for novelty can tip over into playful behavior for animals that have the brain power, the extra time and the resources to think about anything other than their immediate survival.

Pellis notes that octopuses don’t seem to play much in the wild, presumably because they are so busy trying to hide, eat and survive. But given a toy in a tank, they’re like toddlers with extra appendages. Howler monkeys certainly have the brainpower for fun, but they spend so much time lying around trying to digest their high-fiber diets that they rarely bother to recreate, especially compared to their high-flying, fruit-eating spider monkey neighbors.

Even if play serves no evolutionary purpose, it may still be rewarding. Studies show that wrestling rats enjoy a rush of dopamine and other brain chemicals that help to regulate emotion and motivation. The surge of dopamine, which activates the brain’s reward pathway, is especially intense in younger animals — potentially explaining why youngsters of many species are more playful than their elders. As Pellis explains, the dog that lives to chase tennis balls has discovered a way to exploit that reward system again and again. And because dogs have been bred over many generations to essentially act like perpetual puppies, that rush — and the joy that seems to accompany it — never really goes away.

Children also find deep rewards from play. In her years of observing children at home and work, Schulz has been struck by the way children create completely unnecessary challenges and obstacles in the name of fun. Just like other playful creatures, they seem to have an inborn need to try new things. But instead of simply wrestling a friend or smacking rocks together, they’ll spend hours building a cardboard rocket or hopping between arbitrary chalk lines on a sidewalk.

Schulz suspects that this kind of pretend play has some benefits, even if they are hard to measure. “Pretending to fight dragons won’t make you any better at fighting dragons,” she says, but it might be useful in other ways. “They’re setting up a cognitive space where they can create a problem and then solve it.”

The sort of mental flexibility and determination required to fight dragons won’t do a kid any harm, and it might even come in handy in the face of some future real-world challenge. Pretend play may also help children to develop self-controland, paradoxically, help them to understand the line between play and reality, Lillard wrote in a 2017 paper in Trends in Cognitive Sciences. She notes that just as wrestling rats or puppies quickly learn that they can’t actually bite their friends during roughhousing, children who create a pretend world learn that they can’t take their imagination too far: That mud cookie isn’t going to taste great, and that cape doesn’t really make it possible to fly.

Fanciful role play that involves feelings, such as pretending to be scared or triumphant, can help some children understand and control their emotions, says Manfred Holodynski, a developmental psychologist at the University of Münster in Germany. The children have to enact emotions they don’t completely feel. “That requires an awareness of how emotions work,” Holodynski says. But make-believe has its limits. In a 2020 study, Holodynski found that children pretending to be under a magical spell that forced them to smile still couldn’t muster a halfway convincing grin when they received a disappointing present. (As previously reported in Knowable, fake smiles are challenging for adults, too.)

For all of the uncertainties around play, researchers say it still deserves a place in our lives. Lillard says that schools and parents alike should give children the time and opportunity to find their personal play styles, but she cautions that play should be voluntary and enjoyable, not part of a high-stakes child-improvement plan. “Parents today feel very guilty if they are not pretending with their children,” Lillard says. “They’re made to feel that they’re harming their children. But they aren’t. It’s really a shame that they’re feeling that pressure.”

As a mother of four and as a scientist, Schulz has developed her own approach to play. If one of her kids is playing a video game, she has no problem interrupting them for dinner. But if a kid is deep in play, she’ll leave them to their mission, wherever it’s taking them. “We don’t really know what play is doing in early childhood,” she says. “Until we understand it better, we can agree that it’s fun.”

That’s one point that all involved parties — from psychologists to border collies to meerkats — can support. Play is fun, and fun is good.

This article originally appeared in Knowable Magazine, a nonprofit publication dedicated to making scientific knowledge accessible to all. Sign up for Knowable Magazine’s newsletter.

![a photo of a [dog breed] on a pink background.](https://bigthink.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/dog2.jpg)